Webster’s Dictionary defines genius as “…a person gifted with extraordinary powers of intellect, imagination or invention.”

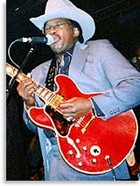

The definition could as easily be applied to describe Howard Roberts – virtuoso guitarist, innovative educator, and indefatigable inventor. Roberts was a guitarist’s guitarist, many things to many people, and enjoyed three highly distinguished and influential careers.

He was an eclectic recording artist with an incredible aesthetic depth that readily embraced jazz, funk, rock, blues, pop, and all manners of experimental music. H.R. was first heard as an inventive and proficient jazz player of the first order, as demonstrated on his straight-ahead Verve releases of the 1950s and slightly more commercial Capitol records of the early ’60s, before embarking on one of the most successful and productive session stints in history.

In Roberts’ second career he was a dominant force in the busy recording studios of Hollywood, playing on literally thousands of auspicious dates; imparting his unique touch and talents to iconic pieces of the American soundtrack like “The Twilight Zone” (H.R. played the series’ haunting and immediately recognizable theme), “M.A.S.H.” (H.R. and Bob Bain laid down the memorable guitar intro), “The Beverly Hillbillies” (H.R. ad-libbing on banjo because the hired banjoist couldn’t read music), “The Sandpiper” (H.R. sightread the gorgeous gut-string parts cold, on a soaking-wet classical guitar), “I Dream of Jeannie,” “The Munsters,” and countless others. Singular among the jazz-based session players of the day, he could rock with the best of them. He even earned the title of “Fifth Monkee” via his participation on a string of Top 40 hits and albums by the Beatle-inspired rock band.

Roberts’ third career was as an educator. In the early ’70s he founded Playback Music and wrote the first modern guitar method books to address topics at the professional level for aspiring players. He went on to write Praxis, created the epic-length Guitarist’s Compendium, and developed the revolutionary Chroma system using color-coded strings to teach basic guitar. Arguably, his most notable contribution to the field of pedagogy was the founding of Musician’s Institute, which evolved from the Guitarists Institute of Technology (G.I.T.), which in turn grew out of his earlier Howard Roberts Guitar Seminars of the late ’60s.

By Fall ’91, H.R. was broadening his educator’s scope to include computers and distance learning, presaging the innovations now surfacing in the medium. In a very memorable conversation, Roberts brainstormed a correspondence course accessed with computer networks (he was talking about information exchange via cyberspace), virtual libraries (the forerunner of music content websites), and interactive components (real-time music instructional devices akin to the Riff Lick interface).

A visionary in all things musical, Roberts was also active in pioneering instrument and amplifier technology. He designed the unusual and highly soughtafter Howard Roberts signature model archtop for Epiphone in the mid ’60s. He later redesigned them for Gibson in the early ’70s. His Gibson Howard Roberts Fusion model has become a favorite for many crossover and rock players including Alex Lifeson of Rush. Roberts and Ron Benson designed and produced the first boutique amps in history with their Benson line of the ’60s. These became a studio standard of the era, presaging the Boogies, Soldanos, Bogners, and Evans of the future.

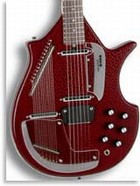

The Black Guitar

The Black Guitar is a truly historic instrument. It was Roberts’ trademark instrument of the ’60s and ’70s, despite the namesake models produced by Epiphone and Gibson. H.R. seemed to prefer this highly-modified and unusually appointed archtop electric during his most active recording and performing years. How many studio dates the Black Guitar graced is a question best answered by archivists; suffice it to say, a great many – and all are important. The instrument is an unmistakable and undeniable voice in the American soundtrack. In the H.R. discography, the Black Guitar can be seen (and heard) on several current CD reissues, including the important two-disc set The Howard Roberts Quartet: Dirty ‘N’ Funky (a compilation of his first two Capitol albums, Color Him Funky and H.R. Is A Dirty Guitar Player on Guitarchives/E.M.I.-Capitol), and the live V.S.O.P. jazz recordings Howard Roberts: The Magic Band, Live At Donte’s and Howard Roberts: The Magic Band II.

The Black Guitar has an extraordinary lineage. It began life as a pre-war Gibson ES-150 (“Charlie Christian” model) of the late ’30s; the first officially marketed electric Spanish guitar. Howard confirmed this fact and in a radio interview of the mid ’60s to promote Color Him Funky, figured its age at about 30 years (his comments and impromptu playing can be heard at www.utstat.utoronto.ca). H.R. acquired the guitar in the ’50s from jazz giant Herb Ellis (VG, August ’96) who remembers buying it when it was new, keeping it as a spare, and finally selling it to Roberts because “…he liked it very much.”

Madeline Roberts (Howard’s daughter, president of the Phoenix Musician’s Union, and a superb guitarist in her own right) recently told us, “That black guitar was the sweetest guitar I ever played. I’ll bet Herb wishes he still had it.”

Despite its innate endearing musical qualities, Roberts subsequently made a number of significant structural changes to the ES-150, reflecting his personal tastes and sonic preferences. The most dramatic are the slimming of the body, the creation of a unique double-cutaway shape, the extension and repositioning of the neck, the replacement of the fingerboard, and the addition of different electronics.

Famed luthier James Mapson (who has built guitars for Mundell Lowe, Ron Eschete, Frank Potenza, and others) recently gave the Black Guitar a professional examination. He studied the guitar for several hours, taking measurements and detailed notes regarding the modifications. His comments presented a fascinating look into the inventive mind of Howard Roberts, the guitarist.

The original Gibson ES-150 was 33/8″ in depth, had a carved spruce top and maple sides and back with a non-cutaway shape, and a 243/4″ scale length on a rosewood fingerboard. Howard had the body reworked into a thinner, more comfortable 23/4″ profile. The labor was done by Nick Esposito, master guitar repairman to the stars of the era, and is verified by a rectangular label glued inside the body, which reads “Esposito Guitar Mfg.” The label also bears the red handwritten serial number HE 500 1957, a possible reference to Herb Ellis and the year 1957. The perimeter of the body, back, and sides has layers of binding under the black lacquer.

“It appears to be a piece of white inner binding, a middle layer of snakewood, finally joined to the outer white binding,” said Mapson. “They probably masked it, originally. The back was cut off to make the guitar thinner – this is the most expedient way. Most likely, the builder needed to fill space around the rims, and since it wasn’t going to show, they used binding.”

These suppositions are substantiated by the fact the original ES-150 had a flat back. The Black Guitar has an arched back (possibly a re-worked arched top) of laminated maple. The solid spruce top and slimmed maple sides are from the original ES-150.

The guitar is further distinguished by its uncommon double-cutaway shape with improved access to the upper register. The top bout (bass side) has a distinctive thumb notch and the lower horn has a more standard Venetian cutaway.

“My guess would be Howard wanted it to look like a conventional single-cutaway guitar yet allow him to reach in with his thumb around the side of the fingerboard. This would be valuable to a thumb-style player (as Howard was), especially one who used the higher frets,” Mapson added.

Interestingly, a similar thumb-notch cutaway has recently been incorporated into the Ibanez Pat Metheny model.

“Normally an archtop of this era would have a 14th-fret neck joint, this guitar has a 17th-fret joint. The block at the neck/body junction is modified and has a larger hunk of maple, which is what would be needed to stabilize the deeper cutaway and joint.”

The original ES-150 fingerboard has been replaced by a longer board with pearl dot inlays and 20 frets.

“I believe this was the original mahogany neck and is now a collage of materials spliced at both ends to accommodate the different position of the fingerboard,” Mapson said.

At one point, Roberts himself re-contoured the neck in stages by applying a material comparable to automotive body putty to the surface. This could be easily shaped and sanded. He would then play the reshaped neck in the dark to fine-tune its feel.

“The new scale length is 251/4″, similar to a concert classical guitar,” Mapson added. “The fingerboard is fairly flat with a slight radius, but takes a pretty dramatic dive after the 12th fret. The board is made from a fine-quality piece of ebony and is very well-built. The width at the nut is 111/16″ and 23/8″ at the 12th fret, which is a little wider than normal. The fret wire is .093″ wide, a slightly wider modern style. The frets have been milled down to 33 height.”

The fingerboard and fret work were performed after the body modifications by master luthier Jack Willock, one of the original artisans of the Gibson Kalamazoo factory, who recognized his craftsmanship when he saw the Black Guitar in April 2000.

The headstock retains the Gibson silhouette, and is fitted with five chrome-plated Grover Imperial tuning keys and one older nickel-plated Imperial. Howard had a liking for these keys, having previously fitted an ES-175 with Imperials in the mid ’50s. The guitar has a custom-made cone-shaped truss rod cover, with no ornamentation or script.

“The top part of the headstock, roughly 1/2″, was fabricated to keep a Gibson look and grafted on just above the top tuning pegs, as indicated by the change in woodgrain patterns,” noted Mapson. “It looks like the side wings of the headstock were also grafted. A lot of surgery was involved here. It’s a miracle guitars like this play as well as they do without buzzing or rattling.”

Part of this miracle must be attributed to Seattle-based luthier/guitarist Jim Greeninger, who recalls doing restoration work on the guitar around 1986. Three tiny holes in the face of the headstock suggest the possibility the guitar had a Van Eps string damper at one point. This further suggests the possibility of George Van Eps having contributed to the final building phases of the neck, as recalled by Patty Roberts. The backward pitch at the headstock is 14 degrees, typical of mid-’60s Gibsons. The headstock shows visible signs of wear (down to the wood) at the top edge. This is probably due to Roberts’ habit of leaning his guitar against a wall on its face.

The entire guitar received a glossy black nitrocellulose lacquer finish, now soulfully checked. According to Greeninger, Roberts painted the guitar himself. Further cosmetic appointments include single binding on the headstock, fingerboard, body edges, and f-holes. Other replacements include Gibson “speed king” barrel knobs for the tone and volume, a ’50s-style Gibson Brazilian rosewood bridge with compensated saddle, and a multiple-bound tortoise shell pickguard (L-5 type) with a gold-plated fastener. The trapeze tailpiece is most likely the only original ES-150 part.

The ES-150 electronics originally consisted of a single bar pickup (the “Charlie Christian pickup”) with two controls – tone and volume – and an output jack at the tailpiece. H.R. replaced the bar pickup in the early ’60s with a quieter P-90 single-coil unit with a black plastic cover that suits the aesthetic. Roberts modified the pickup cover by enlarging the polepiece holes on the neck side so the coil could be moved closer to the fingerboard, no doubt for sonic reasons.

“They probably also ran into interference with the larger neck block and had to fudge it a little to make it fit. However, the position it’s in should give the guitar a nice fat sound.”

The resistance of the pickup measured 8.67 megohms (8,670 ohms), slightly greater than a new Gibson P-90 reissue in an A/B comparison, but probably not perceptible to the ear. The output jack was relocated to the side rim. In the late ’60s, H.R. briefly experimented with a dual-pickup configuration on the guitar. At this point, a Gibson humbucker was surface-mounted and screwed directly onto the top in the bridge position (the body was never routed for this addition). It was accessed via a switching system (two toggle switches) temporarily attached under the pickguard.

Roberts played the guitar through a variety of amps, beginning with a Gibson GA-50, but most often favoring his small Benson 300HR model with a single 12″ JBL speaker for jazz playing, and a larger Benson with a 15″ JBL for other studio dates. According to Ron Benson, the amps were initially conceived as an attempt to improve on the Gibson GA Roberts played and loved in the ’50s.

Today, the guitar has a very woody, live acoustic sound that sings with resplendent harmonics despite the numerous surgeries. The Black Guitar is more than a vintage guitar; it is an historic one-of-a-kind instrument that is part of the American musical legacy of the Twentieth Century.

Memories of H.R.

Howard Roberts was one of my earliest guitar heroes. I was introduced to his music as a young teenager through some of my more discerning rock and roll guitar buddies who had acquired an appreciation for his particular style of funky, blues-inflected jazz. I first heard him on the Capitol recording

H.R. Is A Dirty Guitar Player and a track called “Dirty Old Bossa Nova.” I was hooked, and I was not alone; Howard’s music crossed over, reaching a plethora of rock players in the ’60s, including Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, Joe Walsh, and Jerry Miller chief among them.

A couple of years later I happened across Roberts’ first Capitol album, Color Him Funky. It sent me scurrying to my ’60s catalogs to identify the “weird guitar” on the back cover. It looked kind of like a Gibson hollowbody, but was unlike any I’d ever seen. And to compound the mystery, it had no name on the headstock. After scouring every available catalog, it remained a mystery. Nothing like H.R.’s instrument could be found anywhere. A couple of years later I bought The Howard Roberts Guitar Book, his first instruction manual, with that unmistakable black guitar conspicuously displayed on the cover and in several interior photos. The mystery continued.

H.R. permanently relocated to the Pacific Northwest in the ’70s, and I lost touch with him until 1986, when we happened to be judges at a local guitar contest in Portland. I was just starting my career as a guitar educator and musicologist, and Howard was an instant mentor – forthcoming, insightful, and encouraging about the field of modern music pedagogy. We spent memorable hours hanging out, but never talked about the Black Guitar. Apparently, he had retired the instrument from live performance some years earlier and at the time was using a Gibson archtop (a special-order red model now owned by Mitch Holder).

Howard passed away unexpectedly in June of ’92. His remaining instruments were retained by the family until last year, when his widow, Patty, was ready to see that his equipment found good homes. I purchased the Black Guitar from her in March of ’99; marking a significant closing of a personal musical circle in my life. I immediately began a campaign to investigate and document its origins, with intriguing results. On a related tack, one of the greatest joys and thrills of my life was performing and re-recording Howard’s music for a new generation (“Satin Doll” on the upcoming Best of Jazz Guitar Signature Licks book/CD from Hal Leonard Corp., due out late 2000) on this extraordinary guitar. A mystery for 40 years, now the first installment of the Black Guitar saga can be told.

Photo courtesy of Patty Roberts.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Aug. ’00 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.