-

Deke Dickerson

Gibson Wall-Board Guitar

Out of the Woods, Off the Wall

In the world of “guitarcheology,” it’s well-documented that the truly interesting stuff – prototypes, one-offs, custom instruments – usually surface close to the source. For instance, in the 1970s, Fender prototypes walked into guitar shops in Orange County, California. D’Angelicos are typically still within a few hours of New York City, as they were almost

-

Deke Dickerson

Paul Bigsby’s Myrtlewood Guitars

= Few things are as satisfying as a guitar with a good story to tell. Some vintage guitars might be beautiful and/or valuable, but boring as Paris Hilton – the guitar equivalent to a vacuous model with zero personality. Others, either by virtue of the lives they’ve led or the story of their origin, are

-

Deke Dickerson

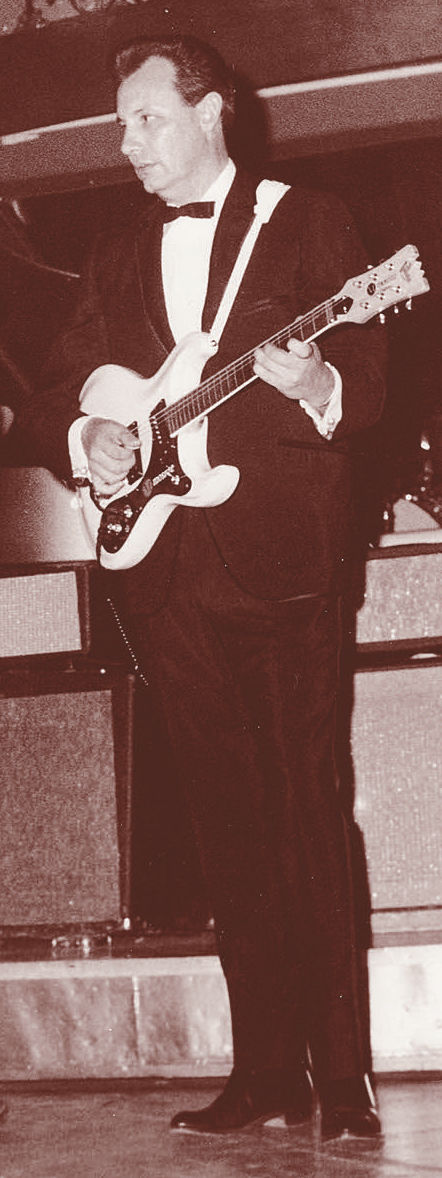

Farewell to a Venture

Nokie Edwards 1935-2018

Nole Floyd “Nokie” Edwards, former lead guitarist and bassist with The Ventures, passed away March 12 from complications related to ongoing medical problems. He was 82. Edwards was born May 9, 1935, in Lahoma, Oklahoma, the son of Elbert and Nannie Edwards. He began playing guitar at age five, as well as the mandolin, bass,

-

Deke Dickerson

Nokie Edwards, Ventures Guitarist/Bassist, Passes

Nole Floyd “Nokie” Edwards, former lead guitarist and bassist with The Ventures, passed away March 12 from complications related to ongoing medical problems. He was 82. Edwards was born May 9, 1935, in Lahoma, Oklahoma, the son of Elbert and Nannie Edwards. He began playing guitar at age five, as well as the mandolin, bass, steel

-

Deke Dickerson

Doublenecks, Triplenecks…

And the California Weird Factor

If you mention doubleneck or multi-neck guitars to your average guitar player, the first thing they’ll likely think of is Jimmy Page playing his Gibson EDS-1275 with Led Zeppelin, or Rick Nielsen and his floor-length five-neck Hamer with Cheap Trick. But few people, even amongst guitar players, realize that the multi-neck guitar has a storied

-

Deke Dickerson

Letritia Kandle

and the Magnificent Grand Letar

Run down the list of early electric-guitar innovators and an all-male group typically comes to mind – Les Paul, Alvino Rey, Charlie Christian, Merle Travis, and the like. However, Letritia Kandle deserves to be on the list, as well – her 1937 Grand Letar being the first “console” steel guitar and the first steel with