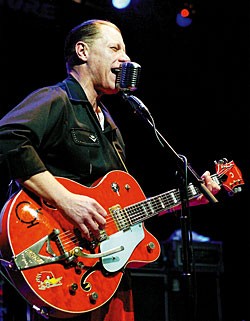

Photo courtesy of Yep Roc Records.

After two decades of constant touring, Jim Heath decided it was time to go home. Guitarists who put out half the energy he expends in concert usually burn out much sooner. Heath, a.k.a. Reverend Horton Heat, stayed home in the Deep Ellum district of downtown Dallas, Texas, to be with his family while he decompressed, opting to record the next album just down the block at Last Beat Studio.

“We travel to play music, and I’m gone so much,” says Heath. “To leave my hometown to have to go sit somewhere to do a recording, that’s just very hard for me to do. I’m away from my family enough as it is.”

Recorded in 10 days, Revival is loaded with RHH’s trademark energy, excitement, fun, and high-octane guitar picking.

Vintage Guitar: Talk about those ascending crosspicking licks on Revival’s title track.

Rev. Horton Heat: I like to try to emulate Merle Travis and Chet Atkins licks. I can’t play much of that Chet Atkins stuff, but I’ve got some concepts from him going lately. The crosspicking thing is something a lot of the country guys who fingerpick while they’re holding a flatpick do.

For the lick in “Revival,” you hold a three-note chord, hit a note with the flatpick, then pull up with your finger to hit that middle note, come back over the top of the middle string and hit the high string with your flatpick, come back up with your finger, then down with your flatpick. It’s a lick you don’t have to do that way, but it makes it very easy to flow in and out of playing straight chords and other fingerpicking patterns. I can get those fast, banjo-style 16th notes through the crosspicking.

One of the great curveballs you throw on this album is “New York City Girls.” What led you to that sound?

That one has some jazzy twists and turns. When we finished our last album, one of the things I got into was Django Rheinhardt. A lot of those are just three note chords, but they sound so fat. “New York Girls” has a Django-style rhythm part to it, kind of mixed in with a little surf riff. It uses minor 6ths, and I’ve been doing that for my whole career.

You have a lot of different guitar sounds and textures on this album. Was it a long equipment list?

Not really. We were trying to get this done as quickly as possible, so my goal was to get one good guitar sound and not change. But that was hard to do because my amps kept going out and we had to switch them out with ones that worked. But our amp repair guy lives a block from the studio, so it worked out. I had guitar trouble, too. My Gretsch 6120W actually got a problem in the middle of the session and I had to switch to the Gretsch White Falcon for a couple things. I used my ’54 Gibson ES-175 a little, too.

Are you a collector?

I have several pretty cool guitars and amps, but I’m not a big collector. I have a ’57 Gretsch Streamliner that looks brand new, which I got from Billy Gibbons. I’ve also got an early-’60s Gretsch Sparkle Jet that’s in excellent condition, and a New American Standard Tele I like a lot.

The ’54 Gibson used to be your main axe. What led you from that to the Gretsch?

I used to use vintage guitars. I’ve got an old Guild Duane Eddy, and the Gibson was about the only one I was using for a long time. But I was having a lot of trouble with it on one tour, and I had all my tour money in my pocket, so rather than re-fixing the Gibson I decided to buy another guitar. I saw the Gretsch 6120W, and it had the hollow body and the Bigsby. The Gretsch can do the jazz thing really well on the neck pickup, but the other pickup can do rock and roll. I can also get a little Telecaster sound that I really couldn’t get out of the Gibson. And it had that vintage tone. Nothing’s like a vintage guitar, but those are all different, too. The Gretsch just worked. We’re a road band. I don’t have time to be fixing all this fancy vintage stuff.

Any chance you’d give away the secrets of your setup?

Sure, I don’t mind. From the guitar I go to an Ernie Ball volume pedal. That’s fun because I can get steel guitar-like swells and a little simulation of an amp vibrato with it. I also have the switch for my echo there. Next it goes to a Boss tuner, then to one input of a Chandler digital delay. I rarely change the settings on that. It always does a simulation of a ’50s-style slapback echo. Can’t be a rockabilly cat without my slapback, y’ know? From the Chandler’s right output it goes to the silverface Fender Super Reverb that’s turned all the way up.

From the other side of the Chandler a line goes to stomp boxes. There’s a Boss analog delay that I rarely use except to make crazy sounds, for when I break a string or when I’m just feeling like an idiot and want to screw around. Then there’s a Boss Blues Driver that’s always on, and then it goes into a blackface Fender Twin. When I record, I can just pan those a little bit side to side and it’s a great big sound.

I get a distorted signal through the Twin because of the Boss Blues Driver, which I can turn up a bit to get just a little extra dirt. In certain rooms that are really small but dry, I can’t turn the Super up to 10, but I can turn up the Blues Driver and still get the dirt. I don’t usually turn the Twin up very loud, because that isn’t really the bulk of my sound. My sound really comes blaring out of that Super Reverb. It doesn’t have any distortion of its own, but I get distortion by turning it all the way up, and by the way I play. If I grind out a little extra, it almost sounds like heavy metal, but if I play a little bit cleaner it sounds like a country thing. It’s hard to get that kind of sound from any distortion device, so I prefer to go that route for most of my sound.

Recently you’ve been playing live with baffles in front of your amps. What’s the reason for that?

People come up and say, “Turn it down a little bit!” But if I’m getting a good sound and my amp is on 9, and I turn it down to 8, it changes the whole tone structure. The baffles let me keep it on 9 and keeps my amps from bleeding too much into my vocal mic. We try to help the people right up front hear the whole band, like the rest of the house can, because those people up front are our best fans.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Aug ’07 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.