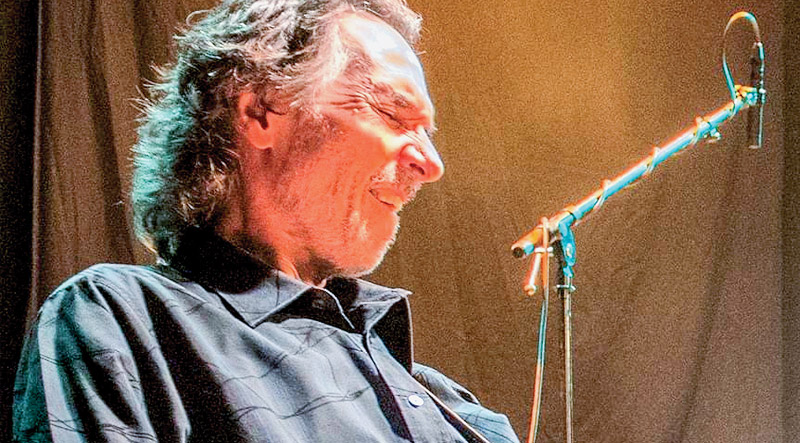

Check out the credits on many jazz, pop, and Latin albums over the past four decades and you’ll see the name Lincoln Goines. As a session player, sideman, and teacher, Goines has carved out his niche as a top-tier bassist for Dizzy Gillespie, Carly Simon, and guitarists Mike Stern and Wayne Krantz. His new solo album, The Art of the Bass Choir, is not only an all-star effort with bass heroes like John Patitucci, Victor Wooten, and Tom Kennedy, it’s also a serious artistic statement.

Was part of the goal on The Art of the Bass Choir to help listeners understand the bass as a harmony instrument?

Indeed it was. I wanted to change the conception of the bass as a rhythm-section instrument, and move it to the forefront. We showcased all the harmonic possibilities of the low end in different multi-bass ensemble settings. I carefully chose and composed pieces in different styles and genres that represented the unique sonority and temperament of the instrument. On most tracks, I play the central trio, quartet, and quintet parts. The guests contribute solos, and in some cases, melodies, additional chord comping, and embellishments. Most of the parts, minus the solo spaces, were arranged and written in detail, and almost all of the contributing artists sent multiple takes.

On “All Blues,” is that some kind of soprano bass taking the melody?

That is my Fodera 33″ five-string, with a high C on top. The higher notes of the melody are played with artificial harmonics.

What’s the story behind that funky chord comping with Victor Wooten on the Herbie Hancock composition “Spank a Lee”?

I played most of the four core parts, outlining the original Headhunters groove and melody. I left some sections open, then asked Victor to add a track. He sent four parts that complemented mine and made the entire piece a cohesive funk symphony; that’s the genius of Victor. Of course, for sophisticated modern funk, there is no drummer on planet earth like Dennis Chambers.

When recording all those basses, did normal EQ rules apply, so you didn’t get a mass of muddy bass tones, as on “Spin the Floor.”

Those rules don’t apply. All my basses are single-pickup, which I find resonate with more clarity than dual-pickup basses. In addition, I panned all the basses wide because I discovered that positioning them together in the traditional manner had a tendency to squash and muddy them. I worked closely with the engineers to not over-compress, and use a minimal amount of reverb. This way, all the dynamics and the natural sound of wood and metal strings would remain intact.

“Velho Piano” has a long, beautiful improv. Is that you or John Patitucci?

That’s John. I play the melody in and he plays the melody out. I re-orchestrated my comping behind his solo after I placed it in the track to enhance and complement what he had done. On the double-time samba ride-out at the end, John and I exchange four-bar trades.

“Three Views of a Secret” has some great chordal work.

That’s a bass quintet, and the orchestrations are based in part on the Jaco and Weather Report versions. I consider that to be Jaco Pastorius’ masterpiece. There are two soloists: Tom Kennedy in the E-major row, and Mike Pope in the G-major one. They are spectacular contributions.

“Vassar Llean” is a collaboration with Ed Lucie from the Berklee College of Music.

That is a lesser-known ballad by the great bassist/composer Charles Mingus, arranged by one of my mentors and influences, bassist Steve Swallow. I spoke to Ed Lucie about the Bass Choir project and he mentioned the hand-written arrangement he had in his attic. We put this together, pretty much verbatim, with maestro Steve’s blessing.

What gear did you use on the album?

I used three Fodera Imperial basses – a five-string 34-inch, a five-string 33-inch, and a fretless 33-inch five-string, all built for me at the Brooklyn shop by Vinny Fodera. I also played my 1875 Italian-built acoustic bass, using a French bow, and I processed the tracks direct through an Epifani Piccolo 1,000-watt head with a custom 1995 Nat Priest DI.

Will you take a lineup of the Bass Choir on the road?

That is a goal for 2023.

This article originally appeared in VG’s February 2023 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.