One night when Bryan Lee was opening for New Orleans legend Snooks Eaglin at the city’s Rock ‘N’Bowl, Snooks called Bryan up to jam during his set. Lee recalls, “He said, ‘All we need now, Bryan, is [blind pianist] Henry Butler, and we’d have the Three Blind Mice.’ I said, ‘No, no, no. The Three Blind Cats – cos we’re cool.’”

Hang around Bryan Lee for awhile and you almost forget that he is blind – or at least question your preconceived notions regarding his “handicap,” because he is self-sufficient at so many things. Waitresses take extra care to let him know where his coffee cup is, where his napkin is, and he’s gracious and respectful, whispering after they’ve left, “What do I do in my own house, ya know?” But, he laughs, “That’s alright. “

Hearing the 60-year-old play the blues erases any lingering stereotypes, and blurs the color line pretty well, too. Lee has been playing guitar onstage for 47 of those years, first in his home state of Wisconsin, but more notably in New Orleans, where he has been a prominent fixture since moving there in 1981. Go to one of his gigs in the French Quarter and you might see B.B. King sitting in the audience, Sting up onstage, or Cyndi Lauper singing blues incognito. Kenny Wayne Shepherd played on Lee’s two-volume Live At The Old Absinthe House Bar CDs (one Friday night, one Saturday night, 1997), along with Mahogany Rush’s Frank Marino, and Bryan returned the favor on Shepherd’s Live On from 1999.

Lee’s latest CD on Canada’s Justin Time label, 2002’s Six String Therapy, is possibly his best to date, thanks in part to the production talents of Duke Robillard (VG, July ’03) and the backing chops of Duke’s band. “It was like a dream come true,” according to Bryan. “We clicked. We all went to the same church.”

Although some reviews rave about Lee’s “greasy New Orleans blues… conjuring the sound of the swamp” (allmusic.com), his style owes more to Chicago and Texas greats, such as Freddie King, Matt Murphy, and Albert Collins, with tasteful dashes of B.B. and Albert King. And his singing is natural and authoritative, filled with power and feeling, never sounding affected.

Now, Bryan is anxious to venture outside the comfort of his adopted home, and bring the blues to “your town.” As he says without hesitation, “My bags are packed. “

Vintage Guitar: Before you started playing blues, were you into rock and roll?

Bryan Lee: Oh yeah. I started listening in the early ’50s, pre-Elvis, to the pop music of the day. The stuff I grew up on with my folks was, like, Perry Como. When I was 10 or 11, I got a radio that could pick up stuff late at night. I got into country music big time – Hank Williams, Hank Snow, Ray Price, Chet Atkins, Les Paul, and Mary Ford. Then I started tuning in the other side of the dial, and I found a station from Nashville, WLAC, and they were playing all black music – blues, rhythm and blues, soul, gospel – and all their sponsors were record stores with mail-order. It was like discovering the Holy Grail.

Elvis and Gene Vincent were cool, and I loved Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash, but then I heard Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley. The first Chuck Berry record I heard was “Maybellene,” and then “Thirty Days,” but the one that really knocked my socks off was “School Day.” And the flipside was “Deep Feeling,” which he did with the lap steel. Holy mackerel! And the first version of “Tutti Fruiti” I heard was Pat Boone – as well as the first version of “Ain’t That A Shame.” So I didn’t know about Little Richard and Fats Domino. When I heard their versions – and Joe Turner’s version of “Shake, Rattle and Roll,” even though I loved Bill Haley & The Comets – there was no turning back for me. It didn’t have anything to do with color; the music was just so much better. It was the feeling, the soul, that hit me. Then I tried to sing like Fats Domino, play guitar like Chuck Berry, scream like Little Richard.

At what age did you take up guitar?

Well, I started fooling around with the guitar around the same time – when I was about 11. At 13 is when I hit the stage, in northeastern Wisconsin, in Two Rivers. I met a guy at the blind school who was a really good guitar player, and I learned a lot from him and was kind of his shadow. We put together our first band. He sang the crooner-type stuff, and tried to get Elvis’ moves down. But he took all the solos and made me play rhythm, so I didn’t play any kind of solo guitar until I was about 17.

That’s actually good training, though.

It was, because it taught me a foundation of chord structure. I remember we opened for Bill Haley & The Comets when I was 15 years old in Green Bay, at a place called the Riverside Ballroom. And Bill Haley told our manager, “This kid Bryan, the blind kid, he’s going to be good. He’s got talent.”

Were there gigs in that part of the country?

My whole thing was, like, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa – that was my turf. But when you’re a draw in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, the rest of the world doesn’t really care. See, people know me from Bourbon Street, but I’ve been in this business a long time. I turned 60 in March.

When I got to be 18, I was basically a road warrior. I had 20 years on the road before I even moved to New Orleans. One of the reasons I moved here was I was sick and tired of driving in snow and cold weather. There was a pretty good blues circuit in the Midwest, especially in the late ’60s and through the ’70s. With the Vietnam war and all the college campuses against the war, blues kind of went along with the rejection of the war, and there were a lot of pretty decent blues clubs in college towns – still are.

I got into a lot of trouble, being in northeastern Wisconsin, because some of the clubs liked the fact that I was singing that stuff, but they didn’t really want any black people coming around. I was doing the Holiday Inn circuit where they want to know how many tunes you’re doing off that week’s Top 40. Eventually, as I grew and decided what I wanted to do, I… how shall we say, “tanned” myself out of a job. Then I gravitated to Milwaukee, and they wanted what I played. But if I was going to stay in the Midwest, I was going to have to set up base in Chicago. I used to gig in Chicago, and got to know Muddy and my heroes, like Albert King, Freddie King. But in Chicago, it was hard because it was very racial. Not the players; it was the promoters. Bruce Iglauer started Alligator Records in ’71 and told me right out, “I’m not interested in you because you’re white.”

I’d come down to New Orleans the first time in ’79, and I noticed that people on Bourbon Street were looking for blues, but there wasn’t any real blues. I’d sit in with some band, and people would go nuts over blues guitar. But there weren’t many guitar players; there were more horn players. And I loved the blues out of New Orleans, like the ’50s. Smiley Lewis is one of my favorites – Bobby Charles, Sugar Boy Crawford. You heard Fats Domino first, but then you found the guys with the grease. I mean, Fats had grease on some of those old records, but they commercialized it, because it worked.

How has the scene changed since you started playing on Bourbon Street?

When I started working on Bourbon Street in 1982, there was a lot of good music on the street – a big variety of music. We even had some great country-rock bands. Up until probably ’93, you were playing original material; people came here looking for something different than they were hearing in other towns. But at some point it was like somebody made a list of songs and said, “These are the songs you have to play. ” So it was, like, “Brown-Eyed Girl,” “Mustang Sally,” “Brick House” and a few others. It’s a shame. The local club scene isn’t like it used to be. It’ll be there at Mardi Gras; it’ll be there Sugar Bowl week and during Jazz Fest. But there isn’t that consistency. You can look at Bourbon Street two ways: It’s steady work, and people come from all over the world, so it’s good exposure. But the other side of the coin is, people think, “Is that all the guy does? Can he tour?” But when we’ve done shows opening for national acts, like with Bo Diddley at the House Of Blues, we rocked the place. The bottom line is, in a situation like that, you have got to kick ass, take no prisoners.

The first gig I played in New Orleans was Tipitina’s, and we didn’t draw flies. No one had heard of us. So we went to some after hours clubs in the French Quarter, and they had these big horn bands, and they let me sit in. A little voice inside of me said, “You’ve come home. ” So in November ’81 I moved down here, and I’ve been here ever since. A lot of that time I’ve been on Bourbon Street, and that’s what most people perceive of me, but I’ve put out nine CDs, even though my record company is in Montreal. If not for Bourbon Street a lot of the other stuff wouldn’t have happened, but on the other side of the coin, because I’ve been on Bourbon Street or in the Quarter for 20 years, people think, “He don’t want to go anywhere.” That’s not true.

Would you like to tour more?

I love to travel; I want to go. But I want an agency. I’ve been to Brazil seven or eight times. Played the Montreal Jazz Festival four or five times. I went to France for 16 weeks in ’97 – in one stretch.

But over there did you find that people expected you to play “Stormy Monday” and “Sweet Home Chicago” and the standard repertoire?

Sometimes, but they just like blues. It’s funny – they don’t speak English, but they can sing all the songs. I got hooked up with a really good French band called Shake On Shake, and I’d just fly over by myself.

Playing a club on Bourbon Street, people might pop their head in the door for 30 seconds and then keep walking down to the next bar. So you’ve got to have an element of showmanship. Is that something you had to work on?

I learned that stuff from going out and hearing Luther Allison and Freddie King – listening to how they’d talk to the audience, how they’d work the audience. Freddie would bring the band way down and walk out to the edge of the stage, singing to the women. I’d never go to shows by myself; I always had “eyes” with me to tell me what was going on. How did they dress? How did they look? Have they got drinks onstage? Are they smoking? What kind of amp is he playing through? I needed to know that stuff. The way Freddie King could hold a note forever – I finally found out how to do that. And it’s amazing: You sit there holding a damn high E for five choruses, and the place is on the floor. I’m just sitting up there thinking, well, I’ve got my pickup in line with the speakers, and I’ve got my feedback note, and it’ll hold as long as the amp can feel it.

You’ve got to put on a show. The thing with blues is, with guys like Freddie King or even Stevie Ray Vaughan, you want to sell this music not just to blues people, but you want to take it further and get more fans. Freddie King could sell it to rockers because of his show and his energy. If three people are in the house, I’m still going to play hard, because, for starters, one of those people might be important. There’s no bad gig. That’s what’s so hard to preach to guys. Every night is dress rehearsal for the big one. Don’t ever take a crowd for granted – because there might be somebody in that crowd who’s important.

Who are some of your other favorite blues players?

A guy who taught me a lot was Luther Allison. He and Albert Collins; the neat thing about those guys is they never sold out. And Matt Murphy is probably my all-time favorite guitar player, because he can play anything. These men were such individuals. You can’t replace a Freddie King, an Albert Collins, a John Lee Hooker, an Albert King. All of this “it has to be by the book” thing; it’s ridiculous. Ignorant compared to what? I mean, I can listen to Elmore James play the same solo over and over and never get sick of him. It’s from the soul.

How did Duke Robillard come to produce Six String Therapy?

That’s one of the greatest things that ever happened to me. I’ve idolized Duke since the beginning of Roomful Of Blues. All the records he’s produced, I think, are excellent. I never met him. He was playing at the House Of Blues, and I took along a couple of my albums. I said, “I know you don’t know me; I totally understand. But I want you to produce my next record. I’ve done as much as I can on my own; I need somebody that I respect and who puts out good records. ” He said, “Well, let me listen to your stuff, and when I get home I’ll call you.” Once Duke was onboard, he wanted to do it at his studio, because it was just easier. Then he asked, “How would you feel about using my band?” I said, “That’s the guys I love. I want to work with professionals.” Then I had to ask myself if I was good enough to work with these people. I’ll be honest, the night before we went into the studio I was scared. After about 15 minutes of conversation, I realized that in spirit I knew these guys. Because they all listened to the same guys I listened to; we all came up the same way. Some of the tunes we did live in one take, because the feeling was there.

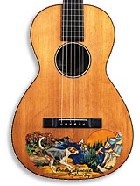

Do you have a main guitar?

Well, in ’93 I had an accident and fell down the stairs in my apartment. I couldn’t play my black ES-355 anymore, because it was too heavy. So I started playing Fenders, and really fell in love with Telecasters especially. For years, that’s all I played. But last night I played a 335, and I held up.

What amps do you use?

Some clubs, it’s hard because there’s no acoustics, and you’ve got to play soft. I’ll use a Fender Deluxe on, like, 4, with a compressor and some overdrive. I can get the Deluxe tone and even out the peaks and valleys, and with the overdrive I can get some warmth and sustain. My favorite amp, though, is my Quad Reverb. When I first heard Albert [Collins] play one, I said, “There’s the amp!”

That’s basically a doubled-up Twin, right?

Yeah. Twin chasis with four 12s. But at festivals, you crank that wide open and you don’t have to worry about nothin’. Albert even played that amp in small clubs, and it was loud, but it was so good.

What continues to inspire you?

If it’s in your soul… I mean, look at B.B. He’s 78, and he’s cut back his touring to 300 dates a year or whatever! I make people happy. Nobody said this was going to be easy. And every time I wanted to quit, something happened to make me keep playing. I believe that the good Lord picked you to do this. Same with the music. This music chose me. It captivated me. It wasn’t the black-white situation or me, a white guy, trying to be black because I think black is cool. I’m probably one of the best ambassadors of racial harmony out here, because I do a black art form that I just adore. It’s sanctified; it’s divine music. I’m white, but so what? I’m blind. All I see is people’s souls.

Photos: Rick Olivieri.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Sep. ’03 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

.jpg)

.jpg)