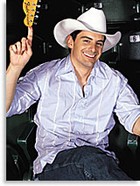

If you need proof that few popular music stars are as comfortable as Brad Paisley wearing the “star hat,” watch his video for his latest single, “Celebrity,” a comedic jab at bigshots everywhere. And Paisley, whose newest album, Mud on the Tires, debuted at #1 on Billboard‘s country chart by moving more than 85,000 units the week of its release, couldn’t be more the polar opposite of the character he portrays – tongue firmly planted in cheek.

When VG first interviewed Paisley in early 2002, his voice was all over country radio and his face was all over Country Music Television (CMT). His second album, II, was on its way to scoring him three top 10 singles, a Grammy award, and all the demands that go along with such accolades.

The newest and youngest current member of the Grand Ole Opry, having been inducted at age 29 and playing on its stage nearly 40 times, Paisley writes or co-writes much of the material he records, uses the same band to record and tour, and though his songwriting skills have some calling him the next Alan Jackson, he’s more like the next Alan Jackson, Buck Owens, Don Rich, James Burton, Redd Volkaert, and Brent Mason all rolled into one.

Whatever the case, Paisley may well be the most real thing happening in Nashville today. We caught up with him on a recent tour stop, where immediately after a hyperextended interview with Billboard magazine, we obliged him while he grabbed a sandwich and talked about guitars, the new album, and some of the players he respects most.

Vintage Guitar: How do you think you’ve progressed as a guitarist on Mud on the Tires versus the II album?

Brad Paisley: Well, I focused a lot more on the guitar playing on this album than I had before.

On the first couple of albums I played a little more like a session player would. They still had me doing what I do, but it was a little more session-like, a “let’s make sure everybody knows I did the right thing for the song” type of thing.

But on this album, I didn’t care about that. It was more about wanting the guitar parts to be unique, and I wanted to go out there a little more. And that makes it even more appealing, from what I hear from other people, than being safe. On this album, the guitar mix is a little louder… We spent a lot more time trying to get onto tape the tone that I get live.

Did you use your Dr. Z amps in the studio this time?

Yeah, we used a big combination of stuff. [The setups] evolved throughout the album, and there aren’t really any two songs with the same exact thing. There was a Z amp on almost every song, though, in one way or another.

My main setup on a lot of them was one of the Z Mazeratis mic’ed – and my engineer really worked to make sure the right mic and right preamp were on each speaker – and we used the 2×12 Mazerati in conjunction with a Z-28 head with an open-back cabinet with a 15″ JBL B-130 from the ’60s. A lot of the songs have that 15 mixed in because I would send a mix to the Z-28 head and compress it a little bit – and I don’t normally use compression of my main setup – and that added some highs and lows that really aren’t present on a 12″ speaker. In the recording setup, it really filled the mix a lot more.

Which other amps did you use?

My ’62 Vox AC30, which we used on two or three cuts.

You’re very knowledgeable about what happens in the studio. Is that a result of you experience in Belmont University’s Music Business program?

I can credit Belmont; I had the Recording Techniques class… I didn’t do very well (laughs), but I had it! I don’t know what they’ve got in their studio now, but at the time they had a 2″ tape machine and early digital machines, which actually didn’t sound good at all – really sterile. So I always leaned toward the 2″ analog thing.

I got to know some recording engineer students who really knew what they were doing and were willing to experiment. I think the trick to getting what you want out of a studio is in part having gotten the wrong sounds. I really don’t think you can do it without getting sounds you don’t like.

So how do you compare what you learned in an academic setting versus what you learned in real-life application?

It’s like anything; they show you this and that, and eventually you figure out that some of it, you don’t need to know!

For instance, in school we learned how to bias the 24-track 2″ tape machines, and I learned to do it… I couldn’t do it now (laughs), but I pretty much figured out that someone else was going to be doing that whenever I was recording onto 2″.

What was your course of study?

I was a Music Business major, and it’s a great program. You can take classes on recording techniques, but your emphasis might be marketing or whatever, which came in a little more handy for me.

Let’s talk about the record. Was the acoustic intro to “Make a Mistake” a one-take recording?

It was, actually, but I replaced the guitar because the acoustic [track in the intro] had some mic bleed. Plus, I started thinking, “It might be really cool to do this Chet-style on a Tele and combine the two pickups.” To me, that lent itself more to the song.

Had I known, I would’ve tracked it that way. But that was all part of experimenting.

Talk about “Spaghetti Western Swing” and its every-turnaround-gets-faster arrangement.

That’s me and Redd Volkaert sitting there with guitars, and it’s the first guitar duet I’ve ever done! We [wrote the song] just to have him on the record, and next thing you know we were adding the narrative because the whole thing became a 1940s radio hour!

I got to know Redd a couple years ago, and he has changed my life. I’ve wanted to cut a duet with him – actually my wife (actress Kimberly Williams) had as much to do with that as anyone…

…did she know him, or had she just heard you talk about him?

She got to see him play down in Austin, and just loved him. Not many people know that he played our wedding reception earlier this year. We flew him out to Malibu, and we were set up close to the beach in a little tent and he played honky tonk songs, and all this Tele stuff! I ended up spending my whole wedding reception onstage with him… which was fine with everybody because my wife got to mingle with everyone, and I got to get out of it (laughs)!

But Redd has become a hero of mine. Coming from a jazz background myself, and having grown up on Hank Garland and Chet and Les Paul and things like that, to me it’s a separate entity than when I would play the Telecaster, which is my favorite thing. With Redd, there’s something about the attitude when you see him play live. You can’t believe the combination of things he infuses into his Tele playing.

He has really shaped the way I play, and I think he influenced this record more than he knows.

There are also a couple vocal duets on the record. How did you go about choosing partners for them?

It’s people who I’m a huge fan of, or just someone I’ve gotten to know. On a track like “Whiskey Lullaby” (with Allison Krauss) I felt there needed to be a female voice for that song to be effective. It’s a great song, but with one guy singing it, it sounds really dark. With a guy and a girl singing it, it’s a little less dark somehow… a little more role-playing maybe. And that’s my favorite female singer, right there!

It was also a thrill having Jerry Douglas play on the album. Jerry is probably the best at his instrument who has ever lived, which you can’t really say about a lot of people. But he is probably the most important dobro player of all time; he’d be the guy to credit for the way people play it today. He’s not doing a bunch of sessions anymore, because he’s out with Allison. But he told me he liked what I do, which was a huge compliment.

You must get your share of offers to do duets…

Maybe not as much as you’d think, but it just comes down to who you’d like to work with. And you do have to be careful, because there are plenty of duets that don’t sound so good.

Talk about some of the broader influences in your music, like maple-board Telecasters from the late 1960s. Country music in the last 10 years has been full of them. Is there some sort of magic there?

That has crossed my mind. You do hear more and more of them, and I feel the maple-capped neck is one of the factors that makes those such good instruments. Something about that neck… it’s twice as rigid, and to me it’s got a little different sound than a solid maple neck.

Also, some of the lightest guitars Fender ever made were from the late ’60s. A lot of people think of early-’50s Teles as being these really light, perfect, guitars. But they were very inconsistent. Most of them had a magic all their own, but some of them weren’t as light as late-’60s Telecasters. Those two factors – a great piece of wood and a great neck… and quality control hadn’t yet gone downhill in the late ’60s.

Anyway, ’68 Teles had a special thing to them, and ’69 models, too – James Burton played one of those – even though by then they had the skunk stripe on the back of the neck. And the reason you’re seeing so many is that they’re sort of the affordable vintage Fender guitar. Mine has a magic to it that I can’t really describe. Bill Crook, who builds my custom guitars, bases them on my ’68 Tele, and some other things he likes from other guitars.

There was a time when the only thing I could play onstage was my ’68. I tried some other guitars, and they didn’t work. So it was nice that he could make some stuff that I could swap out in the middle of a show or use at an outdoor gig where tuning might be an issue…

…and you’re not splattering mud on vintage instruments to do album cover photos…

That’s right! We used a new Crook guitar for that. And by the way, I don’t recommend that for anybody! There are scratches all over it now from that mud.

So it is real mud?! No studio or digital trickery…

Yeah, it’s real. My guitar tech, Zac Childs, had a fit. He was so upset, first of all because he had to clean it off. But yeah, it was a dumb thing to do… and I was really sittin’ in that mud. I looked like a two-year-old playin’ in it!

Will those clothes end up in some celebrity auction somewhere?

Yeah, I imagine They’re hanging in my publicity manager’s office right now, with the mud still on them.

Talk about the path paved by the session guys in the ’80s and ’90s. If there’s a precedent for hot Tele playing today, is it Brent Mason?

In the ’90s he was probably the most important Tele player we had. On most any record you can think of from that era, he was playing it. He’s a tremendous guy and an incredible player, and he was one of those guys who was finally noticed by other genres. He led the charge to bring back country guitar playing.

Before him, though, there were some important people. To me, John Jorgenson is important in so many ways, and underappreciated in the impact he had on music. I remember when Vox amps sold pretty cheap – John was one of the first guys to use amps in an era when everybody else was using a rack – and it’s no coincidence that prices on them started going up when he was out there in the ’80s with the Desert Rose Band, playing through Boss pedals and a Vox amp. And he had that great tone with a Tele when everyone else sounded like they plugged straight into the board….

…and all sounded alot alike…

They did, yes. But John was important, and some other guys led the way.

These days, from what I can tell listening to the radio, there aren’t a whole lot of people in Nashville putting Tele stuff in their records. It’s pretty rare to hear a record where there’s a Tele lick where I find myself going, “Oh, that’s cool!” or “I need to learn that!” or “Who did that?”

Brent is still playing on a lot of stuff, but I think they’ve got him playing a Strat more than a Tele. But in the ’90s, it was like every week you’d hear him playing something you had to learn, whether it was an Alan Jackson record or a Brooks and Dunn record, or you name it.

How would you describe the influence Ray Flacke and James Burton had on your playing?

Ray Flacke… when that Rickey Skaggs stuff came out, it was like, “What in the heck is this?!” I remember hearing stuff like “Highway 40 Blues” and “I Don’t Care.” There’s a guy who had that Tele player’s attitude, and he plugged straight into that an amp with a delay, and it was always unbelievable the way he would bend those big strings. He was responsible for guys goin’ out and buying packs of .008s! To do bends he did with [a thick set]! He was really unique.

But even before him, James Burton was one of those guys who was able to go in and fuse Tele chicken pickin’ stuff on things you’d never dream it would apply to, from Elvis to Ricky Nelson, to the Buck Owens records he played on.

And one of the things that made the paisley Tele cool for me was that James Burton played one. He made it cool, even though it’s pink!

You play on an instrumental track on the new Albert Lee album (see “First Fret: News and Notes” in this issue), Heartbreak Hill.

Yeah, “Luxury Liner,” the old Gram Parsons song, is Albert, me, and Vince Gill. We just went in to jam, basically, and the song makes a great instrumental. I’m really tickled with the way it turned out.

Albert and I have become real close friends, and he comes out anytime I’m in the L.A. area, and he’ll sit in – for the whole show! We’ve got a habit of doing that (laughs). In Austin, Redd does the same thing. It’s fun… I love to make it a guitar thing. And the audience doesn’t know any different – they think he’s some new band member they don’t know. They don’t realize Albert’s the reason we all play Teles!

How has the tour been going?

It’s been a really great year so far. The launch of an album sort of infuses new life into your shows – it’s fun to have some new things to play, even though our work is cut out for us. I’m still trying to learn some of those things I did (laughs) on a couple songs! You know, you do things in the studio at the spur of the moment, but then have to go and do them every night on tour.

But I’m looking forward to the rest of the year, getting out there and pulling off a better musical experience every night. We’re all about trying to play better every night, not just singing hit songs. We ad lib, and every night there’s jamming. It’s almost like the Grateful Dead meets Buck Owens some nights (laughs), because we’ll go off on little adventures. And sometimes we do crash the bus!

For the latest on Paisley, visit brad paisley.com.

THE MUD UNDER THE TIRES

Like any big-time player who doesn’t control much of his own time on the road, Brad Paisley can no longer do much tinkering with his own guitar and amp rig when he’s on tour.

And like anyone else, since he can’t do it himself, he wants the job done by someone who is knowledgable, and who he can trust.

Enter Zac Childs, who has been Paisley’s guitar tech since the Summer of 2002. A friend since their days at Belmont University (“We both failed Recording Techniques [class]!” jokes Paisley), Childs is, according to his boss, a walking git-tar encyclopedia.

“Anything you’ve ever wanted to know, but couldn’t find in a book, just ask him,” Paisley says. “One time, we were talking with [guitarist] Tony King, from Brooks and Dunn, and I said something about a volume pot or something, and Zac said, ‘No, they changed that in ’56… March of ’56.’ And Tony looked at him and said, ‘You’re not married, are you?’ (laughs)! And he’s like, ‘No, I’m not…’ But he is, literally, that bad!”

After graduation, Childs, a respectable guitarist in his own right, played in Nashville, including with Paisley, before moving back to Texas to jockey a desk for a construction firm. Paisley went on to stardom, and for his first few tours relied on tour manager Kris Marcy to pull double-duty as guitar re-stringer. But it ultimately proved too big a handful.

“It seemed that every week something was going wrong – an amp was losing a tube or something.”

The time had come to get an honest-to-goodness guitar/amp tech.

“So we tried some guys out,” Paisley added. “But I remembered Zac in the back of my mind as a friend who knew everything I ever wanted to know about guitars – useless knowledge, really (laughs)! So I called and asked him if he wanted to try life on the road for a weekend. He was hooked.”

For his part, Childs makes managing six guitars for Brad and the band’s other guitarist, Gary Hooker, all the guitar amps, and his boss’ rig sound easy.

“I like to have Brad always playing a guitar with fresh strings,” he said. “So after he plays three or four songs, I’ll give him a new guitar,” he said.

For the record, Paisley plays Ernie Ball .010-.046. “Nothing out of the ordinary about them, and we get them by the boxload!” Childs adds.

And though Paisley’s ’68 will always be his favorite instrument, his Bill Crook custom guitars have become nearly equal allies.

“The black one is his favorite Crook guitar, so he usually starts the show with it,” said Childs.

Paisley’s acoustic instruments include two Larrivee guitars, a D-9 and D-10 with Fishman Matrix pickups, as well as a Gibson F-5 mandolin. The guitars are strung with Ernie Ball Phosphor Bronze .013 to .056 strings.

The effects rack includes two Digital Music GCX switchers, each with eight loops. All the effects run through them to maintain purity of the signal – and avoid having a cable cluster onstage.

“It gives Brad a lot of choices in tonal colors, but doesn’t degrade his tone.”

And what is his typical tone?

“Brad’s typical Tele tone usually uses only a delay unit. We have a few different ones; a Way Huge Aqua Puss, a Boss DD-2, and a Ibanez AD-80 18-volt unit from the ’80s.”

Other boxes in the chain include rackmount Line 6 effects modelers, a Robert Keeley-modified Boss Blues Driver, Hotcake Distortion, EBS compressor (Swedish-made bass unit), VHT Valveulator (for splitting and buffering the signal), DOD Phazer, a Boss CS-2, and an Electro-Harmonix Holier Grail Reverb. He uses a Shure wireless unit.

Paisley’s amp lineup consists of two Dr. Z Mazerati models and a third amp, which can change but is always either a Dr. Z Maz 18 or Z-28.

“We don’t use the internal speakers in the amps,” says Childs. “We use speaker cabs behind the amps, and they have the identical speakers. The Mazeratis are each running cabs with Vox Celestion alnico blues, and the Z-28 is running an old JBL D-130 F – a 15” alnico.

“The Z-28 amp has an EF-86 preamp tube and a 6V6 output tube,” says Childs. “So it has the front end of an old (Vox) AC15 and the power section of a brown (Fender) Deluxe. It’s a great amp, especially running that JBL.”

Photo: Rusty Russell.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Nov. ’03 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.