The assimilation of New Jersey guitarist/bassist/songwriter Glen Burtnik into the bass player slot of the current incarnation of Styx is only the tip of the iceberg concerning the left-handed musician’s experiences. He has written mega-hits in more than one genre, fronted the house band at the Stone Pony, gigged with Marshall Crenshaw, and at the advent of the ’90s, was a guitarist with a platinum-selling band… named Styx.

Yep, this is Burtnik’s second go-round with the Chicago-based mega-band, and when VG caught up with the affable veteran, he was on the road with that aggregation, and was nursing a mild cold, but was up for an on-the-record dialogue about his history, including his use of left-handed instruments, which are strung in a decidedly-different manner:

Vintage Guitar: It’s been reported that your earliest musical experience was singing along with your older brothers, and that they drafted you to harmonize.

Glen Burtnik: Well, I always loved music, but when we’d take family trips in the car, they’d come up with teenage songs to sing, and they insisted that I sing my harmony part all by myself! It was an early persuasion to get sharp harmony skills. I like to blame them for it, but they added a degree of appreciation to my early love of music. We’d sing a lot of hits from the late ’50s and early ’60s, and some doo-wop.

Are you, to borrow a term from Elliot Easton, a “hard-line lefty”? Or do you do anything right-handed?

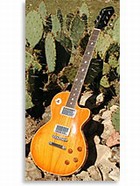

I’m left-handed in every way, and the confusing thing about my guitar play-ing is that when I was a kid, I got a little Stella acoustic and changed the strings to the correct order for a lefty. But my brother had a guitar that was a little nicer, and his was strung right-handed. I was self-taught, and I learned both ways. Eventually, I gave up the lefty-strung guitar. In folk circles, the way I play is called “Cotten picking,” after Elizabeth Cotten; I take a guitar strung right-handed and flip it over.

Albert King style?

That’s right. Hendrix, McCartney, and those guys did it the correct lefty way, but there are a number of us out there. Jimmy Haslip, bassist for the Yellowjackets, plays that way. I’ve got a list somewhere; I met another guy who plays like me, and we had a big conversation, and came up with about 20 names. It’s a very unorthodox style of play-ing, but there are some little tricks that we can get that are hard for right-handed guys, and vice-versa.

How limited are your equipment choices compared to “correct” lefty players?

Even more limited, I think, because a lot of times it’s not a matter of simply turning over a right-handed electric guitar; the knobs are gonna be up under your arm. Jimi Hendrix had no problem with that, but the balance of the guitar is different, too. I sure like it the other way, where a cuta-way is where it ought to be for a left-handed player. When I go to music stores and look at left-handed guitars that are balanced and cut correctly, they’re strung for lefties, not the way I play. So it’s even harder to find instruments I like.

If you buy a left-handed instrument, do you have to do modifications beyond reversing the nut?

There can be others. For instance, Les Pauls have a compensating bridge/tailpiece that’s slanted a certain way. I have a problem with a guitar like that because the way I string it affects intona-tion. A lot of lefty acoustics are designed to “expect” the heavier strings on one side and the light strings on the other. But for the most part, when I deal with Stratocaster-style guitars or Fender-style basses, it’s just a matter of changing the nut around.

When and how did you decide to become a musician?

As I said, my brothers got me started singing, and like everybody else in my generation, the Beatles on “Ed Sullivan” did it. The British Invasion really got me interested, al-though I didn’t pick up a guitar right away; it was a few years later, when one of my brothers brought home a Bob Dylan record and an acoustic guitar. But before that, my parents bought a drum set, and I started taking lessons. So my first instrument was really drums. Yet it was Bob Dylan and folk music that really brought the gui-tar into my life. The Beatles were first, then I went back and discovered Dylan.

What about songwriting?

Right away! My brother showed me an Am chord and an E chord, and I made up a little melody to go along with them, and I was convinced I was a songwriter (chuckles).

Is it fair to say that getting the McCartney slot in the West Coast cast of Beatlemania was your “big break?”

It was the first one, anyway. When I graduated from high school, I didn’t go to college; I expected to become a millionaire musi-cian overnight (laughs). But Beatlemania was kind of like college for me. That’s where I met Marshall (Crenshaw) and a lot of other positive young guys. We were all emulating the Beatles, and the good thing about that show is that there was a level of dedication to learning the music, not just doing it sloppy, like a cover band would. We’d carefully pick it apart; in my case, with the McCartney role, I studied all of the bass lines and learned them verbatim, as well as the lead vocals and harmony parts. It was like studying the masters – Beatle records are so classic, so well-thought-out, well-arranged, and well-performed. It was my tutorial, not only for professional performance, but also for top songwriting. I went right along with Marshall; he was John (Lennon) in the cast we were in, and he’s still a dear friend of mine.

Presumably, you would have played a left-handed Höfner Beatle Bass strung right-handed. Is it the one on your website?

Yep! It was ordered new – lefty body with a righty neck – in ’78. The pickups were updated, not the original staple-type. And while you might think of them as the wrong amps – I do – they got us the U.S./Thomas versions of Vox Super Beatles and stuff like that. Technically, some of it was the wrong gear, but it was as close as they could get at the time. The vintage thing was a lot more underground.

I recall seeing a performance video of Crenshaw’s “Someday, Someway,” and the bass player in his trio was a southpaw. Was that you?

Well, it could have been, though Marshall did have another lefty bass player, Chris Donato. I’ve done tours with Marshall, and the David Letterman show. But Chris was on Marshall’s first album.

You also worked with Jan Hammer and Neil Schon, and co-wrote “No More Lies.”

I’d made an album with Jan, as his guitar player and singer, then he cut two albums with Neil. They called me in to play bass on some of the stuff, and I co-wrote that song, which was their biggest single. I started working with Jan right after Beatlemania, and he had a ’70s Strat in his studio that Jeff Beck had played. As a British Invasion fan, it was kinda cool to be able to hang out with that guitar.

What was Helmet Boy?

That was before that Schon-Hammer thing; it was in the wake of the Knack’s success with their debut album. There were a lot of L.A. bands signed that had skinny ties (chuckles). Some guys I knew through Beatlemania had a skinny-tie band, and they got signed to Asylum Records, I flew into L.A., kind of wrote their single, and sang on some of their stuff. It was just a short-lived project.

After Schon-Hammer, you went back to New Jersey and began gigging at clubs in the Asbury Park area.

Yeah, that was kind of a new college I started. I played in several bands in that area – La Bamba and the Hubcaps, Cats on a Smooth Surface, and others. Members of La Bamba and the Hubcaps have gone on to work in the Max Weinberg Seven. Cats on a Smooth Surface was a band with a guy named Bobby Bandiera, who now plays with Jon Bon Jovi. Bruce Springsteen would come to hear us about once a week when we were the house band at the Stone Pony, and he’d often get onstage and jam. It was also a bit of an education to play with him and hang out with him back-stage, as was all of the consummate house band/cover band work we were doing. I learned a lot about constantly playing in bars.

While I was in Cats on a Smooth Surface, Jon Bongiovi and Richie Sambora came in to ask me to ask me if I’d join their new band, which had just been signed to a record deal.

As the bass player?

No, as their second guitarist/keyboard player, because they didn’t have David Bryan then. In my infinite wisdom (chuckles), I thought they were going nowhere, and I walked away from it. It still cracks me up, even today. But they’re great guys, and I’m still flat-tered that I was asked.

What about your solo albums over the years?

Soon after the Asbury Park thing I signed with A&M and put out two albums, Talking in Code and Heroes and Zeros. That was in ’86 and ’87 – the days of “big hair” (laughs). I used my Gretsch Tennessean back then. I got Neil Schon, Dave LaRue, Bruce Hornsby, and some other musicians to help me out. I got a certain distance with those records – “Solid Gold,” two MTV videos – but I didn’t become the house-hold name I’d thought I’d become right out of high school! Years later, I released a couple more solo albums, and I’m working on one now. The one that came out in ’97, Palookaville, is really the best one I’ve done.

After those first A&M albums, I worked with Marshall for a few years.

How did Styx find out about you?

I’d met James Young [through A&M], which was Styx’s label, as well; we had some common acquaintances and business associates. Jan Hammer’s manager is from Chicago, as was Styx, and he was important in getting me involved with the band.

Ultimately, I got a phone call from Dennis DeYoung, and when my wife answered, she didn’t know who he was (laughs)! Kind of a classic interaction!

Did it surprise you that they wanted you to write, as well?

Yeah, and that was really the only way I would have done it. And it was an inter-esting leap for me, from Marshall Crenshaw to Styx; very different styles of music. But I maintain that variety is the spice of life, and my musical interests are very wide. I’m capable of having a good time with almost any kind of music, as long as I’m good enough to play it. So with Styx, I was kind of the longhaired guy in the band.

On an early late-night talk show appearance with the band, you were sporting “big hair” and playing a pointy-headstock guitar!

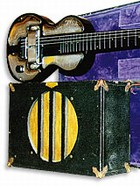

(laughs) I was playing Kramers by that time; it was the era of the pointy guitar. I think they’re kind of silly now, but I keep telling my friends, “Don’t throw ’em away, because sooner or later, there’s gonna be a market.”

For people who were teens in the ’60s, Silvertones and Danelectros are fairly collectible, and the ’80s pointy guitars are far superior, construction-wise.

Danelectros do have a sound; I’m not quite sure what it is, but it’s kind of ratty. Some of the Kramers had a ratty sound. And there’s gonna be some guitarslinger who’s gonna blow everybody away playing a pointy Kramer or Jackson/Charvel.

You appeared on the Edge of the Century album, then you returned to New Jersey.

I wrote or co-wrote about half of the songs on that album.

Ultimate-ly, I ended up making Palookaville when I returned home. But after Styx, I concentrated on doing songwriting for others, because I was impressed with the way I made money from songwriting. I call it “mailbox money;” go out to the mailbox and surprise – there’s a nice check!

I did well with the bands I was in, but songwriting was a happy surprise from time to time.

And that’s when I wrote one of the biggest hits I ever composed, “Some-times Love Ain’t Enough,” that Patty Smyth and Don Henley did. I wrote songs for John Waite, and Randy Travis had a number one country hit with a song I wrote.

In ’99, you got an offer to rejoin Styx, and this incarnation was with Shaw, but without DeYoung.

I always thought Tommy was great. It’s funny; since I’ve played bass here and guitar there, I’ve kind of developed a schizophrenic musical personality (laughs). But I get bored playing just one instru-ment. I also play piano, and if I’m writing a song, sometimes I’ll get halfway through it on guitar, then switch to piano, which helps me look at the song a different way.

Same thing with playing in a band; it’s kind of nice to switch hats like that every once in awhile. So now I’m the bass player, and I was look-ing forward to working with Tommy and everybody else.

Working with Dennis was a bit of a job. He’s a peculiar kind of guy, and I knew right away that this time around, it was going to be a more fun version of the band.

How long had (drummer) Todd Sucherman been in the band?

Todd was playing before John (Panozzo, original Styx drummer) died. I’ve worked with some fine drummers, and Todd is one of the finest. I’m surprised he isn’t more well-known. Working with him forces me to become a better musician. As a bass player, I try to set down a solid groove, and together we work hard on giving the band an updated base to work from.

Original bassist Chuck Panozzo still appears at select gigs. What’s the arrangement when he wants to play?

He plays bass, and then I switch to a Jimi Hendrix Stratocaster.

Your primary performance bass is a beat-up lefty Fender Precision with a carved-up headstock.

It’s a mid-’70s body, and Colin Hodgkinson gave me a ’50s P-Bass neck. Somebody cut off part of it to make it look like a Telecaster head-stock. It’s really quite thin for a P-Bass neck; more like a Jazz. I’m crazy about it; it’s so special. I put it on the ’70s body, and it’s the musical love of my life, so much so that sometimes I won-der if I should take it on the road.

But I also happen to adamantly dis-agree with people who buy guitars and stick ’em in cases, waiting for them to go up in value. A guitar is made to be played, so since I play in front of thousands of people every night, I might as well play my favorite instrument.

On the concert version of “Love Is The Ritual” you stroll into the audience playing a modern Danelectro double-cutaway bass with stickers all over its face.

I call it my “trailer trash” bass (chuckles). A lot of stickers get put on it – the glitzier, the better! I use a dropped D tuning on that song, and sometimes if someone grabs me, it’s probably wiser for me to have something I wouldn’t mind getting knocked around or even losing. Sometimes, it really does get treacherous running through a crowd.

The new DC basses are full-scale, and have a distinct sound.

You’re right, and I like the long scale better. It doesn’t sound like a P-Bass, and I can get away with using it on that song, because there’s also a lot of synthesizer bass on it. That bass is nice and light, and to tell you the truth, I got it off of Ebay for about $150.

As an accomplished guitarist and bass player, have you ever had any problems going from the scale of one to the other, when you had a short-scale bass as an option?

No, you get used to it. I did get used to the Höfner scale when I was in Beatlemania, and I loved it. But to get a lot of true low notes, the longer the string, the better.

And that thin P-Bass neck that Colin gave me makes it easier, too. I’m not that tall, and my fingers aren’t that long, so a thinner Jazz-type neck is easier for me to wrap my fingers around.

Sucherman’s drum kit is impressive, what with the gold rims, etc.

He told me he believes it’s the most expensive drum set in the world. It’s scary, and he’s a real gearhead.

Tommy would understand this, but when it comes to this band, I’m the guy who likes the old, beat up stuff. If it’s too clean, I don’t trust it! That’s why I covered that Dano bass with stickers. It needs to look like it’s been through the wringer a bit. I’ve gone from having the pointy stuff in the ’80s to the “vintagey” stuff now.

Tell us about your annual Christmas benefit.

It started in Asbury Park, but moved to New York, and it’s all Christmas music by a variety of artists. The money goes to New York/New Jersey-area food banks and homeless shelters. It’s called the “Xmas Xtravaganza,” and every year has been great; it has been going on for 12 years. Marshall Crenshaw stops by a lot, the Patty Smyth band has played a lot of times. Buck Dharma (VG, April ’02) from Blue Oyster Cult has played.

I ask everybody to do Christmas tunes, so they have to stretch a little bit. If Phoebe Snow shows up, she’d normally want to sing one of her hits, but I make ’em pick a Christmas song, and it’s kind of cool; they’re not doing the comfortable stuff. But that adds a degree of interest, and a real vibe. It’s a worthwhile project, and some great musicians get involved.

Are the members of Styx planning on any future studio albums?

Right now, I’m working on two albums; we’ve been writing songs for a new Styx album for the last few months. And when I’m home, I work on the solo album. I’m work-ing with a terrific guitarist named Jimmy Leahey on that project. Jimmy’s on Palookaville, too. His guitar playing is so unbelievable that I’m able to concentrate more on bass, piano, and rhythm guitar. We’re a couple of songs into it, and it’ll most likely be on another small indie label.

Glen Burtnik seems to have the best of all worlds, considering his success with Styx, his solo efforts, and his songwriting. He’s genu-inely enthusiastic about his accomplishments and looks forward to continuing his career… even if it means continued usage of a “trailer-trash” bass.

Burtnik and his primary instrument, a ’70s P-Bass with a ’50s P-Bass neck. Photo: Willie G. Moseley.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Aug. ’02 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.