The Ltd was introduced as CBS Fender’s entry into the archtop jazz guitar market. It was to be a prestigious example of Fender’s ability to produce a highly crafted, handmade, unique jazz guitar to stand up to the long-established archtops of the day, particularly the Gibson Citation. The Ltd was the most expensive guitar Fender was making at the time.

Roger Rossmeisl began his career at Fender designing and producing the acoustic King and Concert guitars in 1962. When production of acoustics was transferred to Babe Simoni, Roger became the head of R&D for acoustic guitars, ca. ’66. His job was to design a jazz guitar line with several models to fill the market needs. Roger hired me in 1964 as a production worker in the acoustic guitar division. I continued there after Roger was transferred to R&D and we lost touch for about a year and a half during that period.

After CBS purchased Fender in ’65, a 120,000-square-foot building was erected adjacent to the original nine Fender buildings. The entire acoustic division was moved to the new plant, including the banjo department headed by Dean Markel.

The employee entrance to the main plant was at the rear of the building. As you entered through one of the two sets of glass doors, there was a spacious lobby with the personnel offices to one side and several security people guarding the entrance. There were hundreds of people working there at the time. One morning, in the entrance lobby, there was a large glass case on a pedestal housing Roger’s first carved archtop sunburst jazz guitar. It was a beautiful sunburst with all gold-plated parts. I thought, “So that’s what you have been doing all this time, Roger!”

The guitar was on display because it did not have a name yet. The idea was to ask employees for suggestions. Although I could have submitted as many names as I wanted, I only submitted one – Carousel. The guitar was eventually called the Ltd.

Soon after, I got a call from Roger. He knew I was going to college at night and majoring in metallurgy. He had questions about aging, a metallurgical term. I did not understand why he would call me, perhaps he was just making contact because shortly after he asked me to visit his otherwise-off-limits R&D department. He had just finished designing the Ltd and the Montego jazz guitar, and asked if I would like to be his assistant in the department. I had been honing my skills as a production worker for five years, so this was a great opportunity. In two days I had my own parking space next to Roger, Freddie Tavares, Seth Lover (who shared space in Roger’s building), Harold Rhoads, Gene Fields, and others. This was ca. 1968.

The department was housed in Building 3, one of nine original buildings. Roger had constructed a nice woodworking facility with all the machines necessary for manufacturing the Ltd. There were two large imported German workbenches with 5″ thick solid maple tops with huge built in vices, specially made for violin, cello, guitar making, etc. Fender still has them. We had a buffer, edge sander, shaper, jointer, spray booth, band saw, table saw, and a host of hand tools, many of them Roger’s. There was also a Northstar machine for carving tops and backs for Ltds. We also had carte blanche on any machine in the production department, like the wide-belt sander.

The R&D department was actually titled “Acoustic Guitar Research and Development.” But the department actually did much more than that and was used for any prototype woodwork – electric or acoustic. The main focus was Ltd and Montego production, but we always seemed to have a special project going on the side.

Roger was finishing a project called the Zebra guitar and bass. The Beatles and Stones were major forces, and two groups began to form in London around two styles of music, known as the mods and rockers. These were the names given to the Zebra guitar and bass, the Mod bass and Rocker guitar. The guitars were never produced, only prototyped by Roger. A photograph of Roger talking to Wes Montgomery in front of Roger’s workbench in R&D shows a Zebra guitar prototype on the workbench. The body was solid zebrawood carved like the Ltd jazz guitar. Wes and his brother, Monk, used to visit occasionally.

When I arrived, Roger was ready to begin the production aspects of the Montego and Ltd. He was having the Montego bodies made in Germany. They came in completely glued up with binding installed. They were well-crafted with European woods, spruce and flamed maple that was whiter than American varieties. Montego bodies had arched tops of select laminated spruce. The backs and rims were white European flamed maple, bodies were unfinished, and all painting was done in R&D.

The LTD was a carved archtop with the same rim shape as the Montego. Top and back carving was uniquely Roger’s and was used by his father. The arch shape took place in an area 2″ from the edge of the rim. From the binding the top dipped down .150″, then curved up .350″ all within 2″ from the rim, leaving the raised portion of the top flat. The f holes were machined but not bound, to show the top was solid spruce. The back was carved in a similar manner. Rough carving was done on the Northstar machine, a typical method for rough-carving archtop guitars. The machine has two stations, one for holding the work and one for holding a pattern. The operator controls a hand-held stylus arm that moves around the pattern. A motorized cutter mounted to another arm is connected to the stylus arm. As the stylus arm is moved, the cutter arm responds in exactly the same manner. So a pattern of the top of the guitar would be installed on the stylus side and the wood block for the top appropriately beside it. The operator holds the stylus with two hands, guiding it over the pattern, and the cutter responds, carving the top exactly like the pattern.

My problem was that we had no carving patterns. Roger made the prototype by hand, and making the carving patterns (inside and outside) was a particularly challenging project because of the tolerances. There was also a set made for the back. We would make a batch of about six at a time. The tops would be carved, then sanded. The f holes would be routed, then two independent spruce braces would be glued in and shaped. The top would be glued to the rim. Ltd rims were exactly like the Montego and were imported as rims for the Ltd. The backs would be carved, sanded, and glued to the rim. Just before gluing, Roger would sign and date the label for the inside of the back. The binding was five separate strips installed simultaneously. Roger enjoyed doing the binding and did a great deal of it.

After binding, we prepped the bodies for painting. This was a long, slow process, feathering the contours to perfection. Then the neck slot would be routed and the body was ready for paint. Roger developed a blended transparent color that would be sunburst on after the seal coat. Then the center portion was shot with yellow and a thin coat of clear Fullerplast. All the color would be scraped from the binding, then clear topcoats applied with sanding in between. After drying, sanding, and buffing, Roger would finish the body.

We also made the necks for the Ltd and Montego. The necks were similar except for the head face cap and an inlay strip in the fingerboard of the Ltd. Both head face caps were made in Germany. The Ltd cap had a mother of pearl Fender logo and three mirror image Fs as a design. The Montego logo design was inspired by the marquis at the Tropicana hotel in Las Vegas. The Ltd fingerboard had white binding along the edge and a black/white/black inlay in the fingerboard, just inside the edge. The Montego only had white binding on the edges. The necks were flamed or blister maple with a center strip of padauk, Indian rosewood, or east Indian rosewood. Roger used a double-expanding truss rod in both necks. Scale length was 25.5″ with a medium fret. Mother of pearl position markers were inlaid into the fingerboard.

Freddie Tavares designed the pickups and circuitry for both models. The pickup was a specially developed humbucker developed for a jazz sound. It was attached to the end of the neck and suspended above the top. A beautiful flamed celluloid pickguard material Roger ordered from Italy was made into pickguards, then bound with a multilayered black/white binding. The circuitry was one tone, one volume control, and a miniature jack all in a small brass frame mounted to the pickguard.

We produced only 36 Ltd jazz guitars. Natural finish was offered in the catalog but none were ever made. I saw all 36 but haven’t seen one since I left Fender. I signed a few inside the top, so the only way to see my name is with a mirror. Throughout the time we produced jazz guitars, we were visited by many well-known musicians – Wes and Monk Montgomery, Joe Pass, Jimmy Stewart, Cannonball Adderly, Toots Thielmans. These and others providing many memorable moments and entertainment.

Many other projects came along during the three years the jazz guitar department existed.

Roger left the company in ’71 and moved back to Germany, where he set up his own workspace and getaway. This was where he kept much of his personal property. He took as much as he could then sold and gave me the rest. The jazz guitar department was closed after I finished the last guitars. I was issued one last project at the request of Gene Fields in R&D – the first Starcaster guitar. But that’s another story.

Phil Kubicki began his career in the music industry when he was hired by Roger Rossmeisl, of Fender Musical Instruments, in 1964. His nine-year stay included serving as Rossmeisl’s associate in Fender’s Research and Development department. Currently, he is the manufacturer of the Factor series of four and five-string basses in Santa Barbara, California, and runs a service center making custom guitars and doing restorations and repairs.

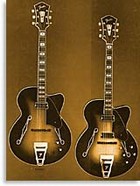

The Montego I and Montego II, from the ’70 catalog.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Feb. ’99 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.