The Ampeg Horizontal Bass, perhaps because of its rarity and odd beauty, has become quite a collector’s item. And because production records for Ampeg products were lost or destroyed after various corporate buyouts, it is impossible to say exactly how many of these instruments were made.

The Mid 1960s

By the mid 1960s, the Ampeg Company, Linden, New Jersey, had displayed great musical equipment achievements and run into sticky economic difficulties. The upright acoustic bass pickup, invented in the late 1940s by company founder and President C. Everett Hull, was still useful. The classic B-15 flip-top Portaflex bass amp, invented at the end of the 1950s by Vice-President and Plant Manager Jess Oliver, was in much demand. The first generation of combo guitar amps with built-in reverb, like the Reverberocket and Gemini I from the 1960s, were popular. But Ampeg had not geared up early enough for the decade’s pop music explosion to fulfill orders effectively. The company was backordered six to nine months, and when orders were finally delivered, many customers had bought Kustom or Standel, Fender or Vox.

The music world had leapt from the big band jazz Everett Hull loved – and which had inspired him to make the sound of his upright bass louder with the “amplified peg” – to the sounds of rhythm and blues and rock and roll. The Motown sound was being driven by James Jamerson’s snaky bass lines, powered by a Fender Precision Bass through an Ampeg B-15 pushed to the edge of overdrive, which Hull disliked. Elvis had revolutionized American pop music, the British had invaded, and it seemed everyone growing up in the ’60s wanted to get with it, buy a guitar and an amp, and wail. Ampeg had tried to sell imported “Burns by Ampeg” basses and guitars – but they were too expensive to catch on. Despite impressive growth in its product line and factory space, Ampeg was stuck in the past. An advocate of clean amp sounds, Hull was shocked when Gibson offered musicians an electronic distortion box!

By 1966, Hull (at age 62) was worried about the company’s cash flow and the value of his stock shares, so he began wooing corporate suitors to buy and support Ampeg. He still wanted to produce his seasoned line of products and serve the needs of jazz musicians, although the future of the business lay in serving pop and rock groups. Studio musicians who had used upright basses and Ampeg’s Baby Bass – the portable plastic-bodied electronic upright, whose sales had stagnated since its introduction in 1962 – were being asked to use horizontal basses, like Fender’s Precision or Jazz. The opportunity for a new Ampeg product presented itself. According to upright bass virtuoso Gary Karr, an Ampeg endorser in the ’60s, Hull had said to him, “I want to put a dent into CBS’ Fender.”

Design

Jess Oliver, evidently with Hull’s blessing, looked to the future and asked Ampeg quality control specialist and Service Manager Dennis Kager to design a new Ampeg bass. Kager had joined Ampeg in 1964, at age 21, and then quickly rose through the ranks. Both Hull and Oliver admired him for his troubleshooting expertise and his inventive imagination. Kager got to work. By March 30, 1966, he had filed his patent for the “ornamental design,” Ampeg’s new instrument.

The shape of the instrument was inspired by Kager’s own favorite axe at the time, the Fender Jazzmaster he played in The Driftwoods, one of north Jersey’s most popular bands. The Jazzmaster’s long bass bout and shorter treble bout were reflected in what Ampeg would advertise initially as the “new Ampeg Fretted Bass,” Model AEB-1, referred to nowadays as the Ampeg Horizontal Bass or F-Hole Bass or Scrollhead Bass. Kager’s original idea for the headstock shape was triangular, which would have permitted a catchy “A” logo, but someone – probably Hull- decided to use the scroll-style headstock of the Baby Bass, which linked the new product to the past, and allowed Ampeg to utilize known production methods in late 1966.

The distinctive elements of the new bass included F-holes, cut through each bout of the instrument’s four-piece semisolid maple body with plywood back. Originally, the F-holes were to face in the same direction, but in production it was decided they should be opposed. The neck was maple with either a rosewood or ebony fingerboard, with a zero fret. Besides the rectangular muting bridge cover, which was adjustable, another unusual feature was the overall string length – 45″ with tuner windings, from the tuners to the extended block tailpiece with nifty dual strap buttons, helpful for stability when the bass was set down and leaned against an amp. The long, custom-made LaBella strings made the action somewhat stiff – despite the traditional 34″ scale length – putting strong pressure on the bridge/pickup assembly, necessary for the effective functioning of Ampeg’s “Mystery Pickup.”

“Mystery Pickup”

Ampeg tipped its hand about the mysterious transducer when it printed the patent number of its 1963 Baby Bass pickup on an early set of “operational instructions”: the pickup for the new Ampeg bass was a modified version of the older one. Now the aluminum bridge would sit on a Bakelite pedestal, which itself rested on a “silectron steel” diaphragm. Under the diaphragm, two magnets and two large coils – nested in a block of epoxy – would translate the acoustic vibrations of the strings, bridge, and diaphragm into electrical impulses for amplification. This arrangement would permit the use of non-magnetic gut strings, not just steel or tapewound, and would – it was advertised – simulate the sound of an upright acoustic bass.

“I never liked the sound of it,” Dennis Kager revealed in an interview, speaking about the Baby Bass pickup and its application to the bass he designed. “That’s why on the original Horizontal Bass, I wanted a magnetic pickup on there.” But this was not to be, at least at first.

The tone of an AEB-1 is an acquired taste, ranging from dark and boomy to abrasively nasal with odd overtones at the extremes of tone setting. Some owners turn down the treble nearly all the way, then tweak their amps to produce decent upright-bass-like depth and timbre. Others – like The Band’s Rick Danko – installed a P-bass pickup and did away with the mystery pickup. Good strategy for instantly-usable tones, but not so good for vintage value! Originally, these basses listed for $324.50 – while now they cost an average of about $1,000. A popular early endorser was Joe Long of the Four Seasons, who used an extremely rare lefty AEB-1.

The Fretless Revolution

Besides the oddly-gorgeous appearance of the first Horizontal Basses – available in “cherry red, white, blue, and burnished tones” – Ampeg could be proud of its revolutionary development of a fretless version, Model AUB-1, four years before Fender would offer this option on its P-bass in 1970. It seems the AUB-1 was more popular than the AEB-1, as upright bass players and others sought the model with the smooth fingerboard. The first AUB-1 may have been made for symphonic soloist and Baby Bass user Gary Karr, who was not comfortable with a fretted instrument. Introduced at the July, 1966, NAMM show in Chicago, and put into production late in the year and in 1967, both the AEB-1 and the AUB-1 caused a stir, but no great bounce in sales, probably because of the limited sound quality. The AEB-1 and the AUB-1 are, nevertheless, the more numerous of the Horizontal Basses.

Metamorphosis

Throughout 1966, Everett Hull stepped up his search for a corporate buyer. He must have sensed the economic hard times ahead for the music equipment business, due to increased competition and product glut. Certainly, he knew Ampeg’s precarious position, along with its potential. Ampeg’s sales had grown roughly tenfold in a handful of years, culminating in the nine month period ending in February, 1966, with net sales of over $2,290,000.

But all this was in jeopardy. He needed to back up his life’s work with strong capital, and he wanted to cash in on his stocks while he could. He had a deal signed, sealed, and delivered – it seemed – with AVNET corporation, but Lester Avnet backed out at the last minute, in the early fall of 1966. Dynaco pursued Ampeg, as did Hammond and Pickwick, but those deals also went unconsummated.

On the personnel front, amp designer Bill Hughes had signed on in Ampeg’s engineering department, and jack-of-all-trades Roger Cox had moved into sales, then product development – both in the mid ’60s. These men would later make their marks at Ampeg by creating huge, powerful amps for mass -audience, big-time rock and rollers.

On the other hand, after over a dozen years of a productive but sometimes wrangling business relationship, Hull and right hand man Jess Oliver parted ways over stock options and job security – and maybe Ampeg’s introduction of solidstate amps – in late September of 1966. Oliver set up shop as Oliver Sound, and began producing his own line of musical products – including the Powerflex amp, a redesign of the B-15 with a motorized head, and the Orbital Sound Projector – a mini Leslie cabinet.

Finally, in 1967, a group of investors and managers began planning the acquisition of a high-profile music manufacturing business. The goal? To form a major music equipment conglomerate and ride the boom in rock and roll. The name? Unimusic, as in “unified” or “universal” music company. The music business to buy? Ampeg! After lengthy negotiations, Unimusic – under the leadership of Al Dauray, Ray Mucci, and John Forbes – bought Hull’s company in September of 1967, making Everett Hull and his wife, Ger-trude, wealthy.

Les Paul recalls Hull visiting him to discuss the sale. Dennis Kager left Ampeg at this time to start Dennis Electronics, which became one of the largest electronic equipment service centers in the U.S. He continued to consult with Ampeg, and eventually designed and marketed Sundown amplifiers. Hull – long used to being the captain of the ship at Ampeg, but scarcely consulted as Unimusic looked ahead – resigned in October of 1968.

The Devil In New Jersey

Ampeg made a last stab at a bass with the mystery pickup in 1967 and early 1968, the scarce and odd-looking Model ASB-1, nicknamed the “Devil Bass” because of its prominent, scary horns. Woodshop worker and former coffin maker Mike Roman had been impressed by Danelectro’s Longhorn Bass, so he urged Ampeg to make its own version. The dual-cutaway body allowed extraordinary access to the upper register, another Ampeg innovation – and of course, Ampeg offered a fretless companion, Model AUSB-1. Both models were available, like their cousins, for the list price of $324.50. But by 1968, under Unimusic, it was clear to the company’s new leadership that the mystery pickup models had to go.

New Pickups

In mid 1967 and 1968, Ampeg experimented with a small number of short-scale Horizontal Basses – the fretted Model SSB and the fretless SSUB – using a magnetic pickup with four visible polepieces. The tone of these instruments, despite their dinky 301/2″ scale, was surprisingly good. An intriguing feature of the fretless model was an F-hole pickguard mounted on a solidbody. Unlike the longer-scale basses, before and after the SSB, the short-scales lacked adjustable bridge saddles for intonation adjustments. The headstock on these small basses, favored by Television bassist Fred Smith, went back to Dennis Kager’s original A shape. Colors available on this limited production instrument were “apple red, black, or gold sunburst,” with an occasional blue. The list price? An economical $189.50.

By the summer of ’68, Ampeg – now called “A Division of UNIMUSIC, Inc.” – was testing a new, larger magnetic pickup, its four polepieces concealed beneath a plastic cover, for the last vintage generation of full-scale Horizontal Basses. At the end of ’68 and into ’69, Ampeg produced a trickle of the new basses – Models AMB-1 and the fretless AMUB-1 – for $324.50 again and then, oddly, for $325, in the fall of 1969. Various-hued AEB-1s and AUB-1s were still in stock and advertised for sale. The magnetic-pickup Horizontal Basses – far fewer of these were made – are the ones to find and play, if tone is the name of the game. The four polepieces of the new pickup were wired alternately, creating a spectacular humbucker that has – if the epoxy sheath hasn’t cracked and fractured the coil wires – a wide range of rich tones, with a deep growl and piano-like singing overtones.

The body construction of the new basses had grown more advanced. The earlier Horizontal Bass bodies had four parts, glued after shaping: the two F-hole bouts, the center block with routing to make space for the “mystery pickup,” and the plywood back. The magnetic-pickup bass bodies and their F-holes were carved smoothly from two or three pre-glued pieces of maple with more sophisticated routing machines. The earlier bass bodies had balanced red and black burst paint around the F-holes – or the custom colors – while the new bass bodies barely showed the standard cherry red under the black overcoat. The tailpiece was incorporated on the end of a bridge plate, shortening total string length to about 43″, with windings on the tuners. The large, rounded bridge cover sported the new Ampeg logo – a stylized “a” or “helmet head.” The earlier “Mystery Pickup” had been concealed beneath the bridge, but now, the adjustable magnetic pickup was plain to see, mounted through the pickguard between the bridge and the neck.

Ebony was now the wood of choice for the fingerboard. The volume pot had a “pull to kill” function, so gigging musicians could turn off the axe without turning it or the amp down. But the bass was not a money maker, so its production was terminated before 1970, ending for a quarter of a century the illustrious career of a weird and wonderful instrument.

Oddities

Besides the main Horizontal Basses, it is worth noting a few intriguing oddities. Chief among them are the two scrollhead 6-string guitars shown at the July, 1966, NAMM show in Chicago, when the first AEB-1s and AUB-1s were introduced.

One of these prototypes – like the one pictured in George Gruhn and Walter Carter’s Electric Guitars and Basses, A Photographic History – is the spitting image of an early Horizontal Bass, including prominent F-holes and a large black pickguard, along with two pickups and a whammy bar. The other, pictured here probably for the first time, is an elaborated version of the first, with subtle F-holes, along with three pickups, a whammy bar, and checkered binding. Where are these unique instruments now? Also, after Mike Roman left Ampeg, he seems to have continued building basses and guitars of his own, but hard information is sketchy on this point for now. Lastly, there are some Japanese-made Horizontal Bass clones. These can generally be distinguished by the anachronistic extended block tailpiece (AEB-1-style) together with an original magnetic pickup (AMB-1-style) and sometimes by the lack of a zero fret.

The Late 1960s

By the late ’60s, Unimusic, with Al Dauray, Roger Cox, Bill Hughes, and others, was in hot pursuit of the rock and roll market, facing the future, but unaware of the impending pitfalls of music business competition, a dipping economy, fickle investors, and personal tragedy.

Everett Hull was retired, travelling and spending time with his family, dreaming of making the Baby Bass popular again. Jess Oliver and Dennis Kager had new businesses. Ampeg – having invented the SVT bass rig and the V-4 guitar stack, among scads of other music products – seemed ready to compete against Acoustic and Marshall in the wattage wars of the 1970s. Suddenly, the Rolling Stones were using Ampegs on the 1969 and 1972 tours. So would The Faces and, later, Black Oak Arkansas. There were cool new Ampeg basses made from clear plexiglass by Dan Armstrong. There would be cheesy Stud basses made for Ampeg offshore in the mid ’70s. But there would be nothing like the adventurous and weirdly wonderful Horizontal Basses from Linden, New Jersey – until a contemporary California inventor would set up his design shop, Extremely Strange Musical Instrument Co., in 1994.

Linden Again

Twenty-five years after Ampeg stopped production of the Horizontal Basses, Bruce Johnson decided he would devote his skills as a mechanical engineer to updating the classic Ampegs.

His first bass – an Ampeg “Devil Bass” – was an inspiration. In the machine shop where he lives, on Linden Avenue in Burbank, Johnson began collecting and analyzing data on the old Ampegs, planning how to create a cutting-edge version of the AEB-1 and AEB-2. He wanted to make an instrument that would have the odd attractions of the original but that could function at the top level of the modern-day music profession. Today’s Ampeg company, under current owner St. Louis Music, introduced Johnson’s AEB-2 and AUB-2, at the winter NAMM show in Anaheim. The new bass is no reissue: it is a redesigned, high-tech instrument that combines tradition with innovation, an Ampeg hallmark.

The AEB-2’s look, along with that of its fretless brother, is well-rooted in Ampeg’s past, but its construction and electronics are spaceage. The scroll headstock is now carved from the solid maple of the neck, instead of having the plastic scrolled end-caps of the original. A brass nut block above the zero fret adds sustain, replacing the aluminum string spacer on the original. The stiff neck is slender throughout its length, supported by “…a proprietary truss rod and neck reinforcement technique,” unlike the sometimes-clubby neck of the old bass. The scale length is a modern 35″, while the body is now ash with a durable polyurethane paint finish in classic black/red sunburst, solid black, or natural. The active electronics combine piezo crystals in the two-part aluminum bridge saddles with a magnetic pickup and custom preamp designed by bass pickup expert Rick Turner. The extended tailpiece is now a 1″ thick block of brass anchored by brass bars deep in the body, enhancing sustain and counterbalancing the long neck.

Reports from NAMM indicate that interest in the AEB-2 and the AUB-2 was high among players, dealers, and the press. Evidently, another chapter of Horizontal Bass history is about to be written. It must have something to do with the classic Ampeg vibe and the range of modern sounds the new basses produce – from the old jazzy upright timbre to the new punch of rock and roll.

“These basses have growl and snarl in the bottom end together with clear highs,” explains Bruce Johnson.

Serial Numbers

Serial numbers can be found in two places on the Horizontal Basses. For the AEB, AUB, ASB, and AUSB models (all with the “mystery pickup”), look under the block tailpiece. For the SSB, SSUB, AMB, and AMUB basses (all with a magnetic pickup), look on the bridge/tailpiece plate. The serial number prefix M, perhaps for “Master,” seems to indicate a prototype bass. The serial number suffix C may indicate a “Custom .” Serial numbers run chronologically, but mixed among the various models of basses, as if the relevant parts for the different models were kept in one bin. Serial numbers seem to run from 1 to nearly 1,200, then start over, with a triple zero prefix, from 0001 to nearly 000600.

Horizontal Bass Users

Joe Long the Four Seasons – lefty Model AEB-1

Rick Danko The Band – Model AUB-1

Boz Burrell Bad Company- Model AUB-1

George Biondo Steppenwolf- Model AMB-1

Fred Smith Television – Model SSB

Billy Rath Johnny Thunders’ band – Model AEB-1

Michael Been The Call- Model AMB-1

Christ Novoselic Nirvana Model AMB-1

Chronology

Early 1966 – Dennis Kager designs Horizontal Bass with F-holes.

July, 1966 – Horizontal Basses introduced at Chicago NAMM.

Late 1966 to 1967 – Production of AEB-1 and AUB-1 basses (most numerous, perhaps 1,200 made).

1967 and early 1968 – Production of ASB-1 and AUSB-1 “Devil Basses” (rare, perhaps 100 made).

September, 1967 – UNIMUSIC buys Ampeg.

Mid 1967 to 1968 – Production of SSB and SSUB basses (very rare, perhaps 50 made).

Late 1968 to 1969 – Production of AMB-1 and AMUB-1 basses (hard to find, perhaps 600 made).

Late 1969 – End of vintage Horizontal Bass production.

Late 1996 – Start of contemporary AEB-2 and AUB-2 basses (available!).

Note: Production figures are estimates based on incomplete information, since no relevant records have survived.

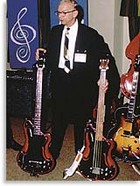

Everett Hull presents the fretted and fretless Horizontal Basses to his salesmen, NAMM, July ’66. Courtesy E.A. Hull.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s March ’97 issue.