Epic poetry is great, but all these long treatises on the massive guitar pedigrees of Kay and Aria have made me feel a bit like a Milton scholar, a fate not to be wished anyone. The Fall was bad enough. So, how about a little lyric poetry, something fresh for a change, some lighter fare at the bountiful buffet of guitar history. Let’s take a peek at Fresher Guitars from Japan.

I don’t remember when I first heard of Fresher guitars, but somehow I knew they’d made guitars with built-in effects. Anything goofball like that is, as you know, right down The Different Strummer alley. So, when I saw a VG classified placed by Nils Freiberger from the Boston area offering one for a reasonable price, I figured it was time to hook up with one. As it turns out, Nils traveled for work and was coming down my way, so we hooked up on a chilly windy Winter day and over cheesesteaks in an old 19th Century cast-iron corner restaurant in South Philly, talked guitars and did the deal.

Now that I had one, what was it? The knowledge quest had begun. There’s a chapter on Fresher in “History of Electric Guitars” (Player Corporation, Japan, ca. 1985), a book which is highly recommended if you can find a copy, but unless you read Japanese, this is not terribly enlightening. Fortunately, Hiroyuki Noguchi, editor of Rittor Music’s Guitar Magazine in Japan, was able to supply some outline information to help us fill in a few of the blanks.

Fresher is hardly a household name in most American guitar collecting families, with good reason. Basically, these were primarily made for domestic use in Japan, although at least some were briefly exported at least to the United Kingdom. Despite the fact that examples occasionally show up, as of now there is no evidence that Fresher guitars were ever officially imported into the United States.

The Fresher story begins back in 1973 when Fresher guitars were introduced by the Kyowa Company, Ltd., of Nagoya. Nagoya, you’ll recall, is one of the principal guitar-making regions in Japan. Kyowa was primarily a trading company, importing products and developing some musical instruments. The company is still in operation, importing Charvel/Jackson, Takamine and Dean Markley products, among others.

Fresher guitars were built by the Matsumoto Musical Instrument Manufacturers’ Association, a consortium of suppliers in the Matsumoto region. This organization, by the way, did not include either Fujigen Gakki or Matsumoku, the area’s more famous manufacturers.

Little is known of these early Fresher guitars, but Mr. Noguchi recalls them as being pretty much low end instruments when compared to other brands available at the time, including Greco, Tokai, Guyatone, Fernandes and Ibanez. Based on the evidence of slightly later designs and the vogue for copying at the time, it’s probably safe to assume these were mainly inspired by popular American designs.

Illustrated in the “History of Electric Guitars” are three guitars which probably reflect this early line. The FL-331 was a white Les Paul Custom copy, with gold hardware, bound ebony ‘board, block inlays and a pair of gold-covered humbuckers. This appears to be a glued-neck guitar. About the only difference seems to be a slightly exaggerated center dip on the open-book headstock. The FN-281 was a copy of the Fender Competition Mustang done up in a blue finish with white stripes, maple fingerboard and black dots. The FN-384 was a black copy of a Rickenbacker 4001 bass, complete with triangle inlays.

As the Seventies progressed, quality began to improve and designs to get more original. In 1977, Fresher introduced the onboard electronics for which it will, most likely, be best known in guitar history. Initially three “Built-In 5 Effects” models were a Strat copy, like the one I got from Nils, a Les Paul and a Firebird.

At least two numbering schemes have been encountered for the same models of guitars, and there’s no way to tell if the number is a clue to sequence, or whether the numbering relates to different markets. Since these model numbers don’t appear on the guitars themselves, such a distinction is probably academic. We’ll leave that to the Milton scholars!

The Strat was both the FS-1007 and the FSC-100. This was a copy of a late-’70s Fender Stratocaster with a white ash body, solid bolt-on maple neck, big Fender-style headstock, brass nut, maple fingerboard, black dot inlays, three single-coil pickups, an adjustable bridge/tailpiece assembly, a pickguard that looks like a Strat except for a sort of genie tail on the lower bout where the electronics controls were mounted. In lieu of a traditional fiveway select, the FS-1007 had two threeway minitoggles which controlled either the front and middle or back and middle pickups, both sharing the middle pickup, in a most curious arrangement! Each of these was then hooked up to separate volume and tone control, yielding four knobs rather than the usual three. Finish was natural oak.

Of course, what’s more of interest here are the onboard effects. Because it is so curious, let me quote at length from the catalog which Mr. Noguchi kindly faxed to me. This is written in that wonderful English which I’ve come to recognize as typical Japanese translation. You may be amused by the errors in grammar and syntax if you’re not familiar with this style, but it reflects what happens to the intrinsic differences in two languages with quite disparate etiologies when they collide in the form of advertising hype!

“‘FRESHER’ JUST CREATED NEW FANTASTIC ELECTRIC GUITAR. ‘FRESHER’ have developed just new fantastic electric guitar in which body 5 Effectors are enclosed compactly, so that players can freely creat [sic] their own fantastic effect sounds just by momentary arrangement of the switches and controllers without any troublesome setting like as pedal system effectors.

“No only individual effect sound but alternative sound by mixing effect sounds can be made. Of course, the normal sounds can be enjoyed. Also, players can change the order of connector between AutoWah and Phase Shifter.

“Now, players need not to carry effectors separately and to connect them with cords. So. Free from noise. Free from setting trouble. Economical costs rather than the total costs of electric guitar plus five effectors. Only ‘FRESHER’ satisfy the demand of Jazz Rock guitarists who are enthusiastic to have new sounds.”

The five onboard effects included phase shifter, auto wah, sustainer, distortion and power booster. These were controlled, overall, by a bypass minitoggle allowing you to kick them in or out at will. Three additional minitoggles then controlled the five individual onboard effects. Each of these then hooked up to a separate potentiometer which basically served as a volume or speed control, depending on the effect. Simplest to operate was the sustain, which had its own toggle for off or on. The other two operated with a threeway toggle, both off in the middle. One controlled either auto wah or power boost, the other either phase shifter or distortion. In essence, you could have up to three of the five effects in combination at any one time. Finally, there was a little red battery power light.

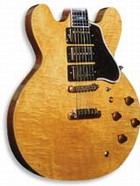

The Les Paul was called both the FL-1005 and the FLP-100. This was a pretty good reproduction of a Gibson Les Paul Custom, with a solid carved maple top over a mahogany body, a glued-in mahogany neck, Rotomatic tuners with tension controller, bound headstock and fingerboard (no split diamond on the head, by the way), block inlays, brass nut, twin humbuckers, threeway select, twin volume and tone controls, elevated pickguard, finetune bridge and stop tail. The FL-1005 came outfitted with Gibson strings! This was available in a natural oak or tobacco brown sunburst. Unlike a Les Paul, however, this had the Fresher Built-In 5 Effects.

The Firebird was called the FF-1003 and the FFD-100. This handsome devil was a neck-through-body guitar made of all-mahogany. The headstock was carved bi-level and two-tone, just like a real Gibson. The rosewood fingerboard was bound with dots. It had a brass nut, combination bridge/stop-tail, two mini-humbuckers and a black pickguard which began like a Firebird but stretched all the way down the guitar to hold the electronics. On the lower horn were two toggles, a threeway select and the effects bypass switch. Otherwise, the effects were the same.

OK, so how do they work? Well, based on the one I have, not bad, all things considered. As usual with onboard systems, the effects tend to be a bit “thin,” and switching is noisy, something that often happens as these guitars age. If you are an effects purist, you want a good pedal. But if you like those cheezy effects that can only be gotten with an onboard circuit board, these are pretty cool. And like the copy says, you don’t have to schlepp around a bunch of pedals and cords.

Actually, the guitar I have differs slightly from the guitars shown in the Fresher catalogs I’ve seen. Mine is called a Fresher Straighter (which the others may be too). Unlike the previous guitars, which have the logo written in an angular script, mine has the logo in a Fender-style spaghetti script. The Straighter is wrapped along the lower edge of the headstock much like the word Stratocaster on a Fender. Stand back and squint your eyes and you’d swear it said “Fender Stratocaster” instead of “Fresher Straighter!” Mine also has a more traditional fiveway select and one volume and two tone controls, like a normal Strat. Mine also has a rosewood ‘board with pearl dot inlays. Otherwise, it’s the same. The strings on mine pass through the body and are secured with ferrules.

Another version of the Fresher Straighter was made with a traditional Fender-style vibrato.

It’s not clear how long these effects guitars were made, but probably not long. I’d be surprised if they made it to 1980.

Textual evidence from the catalog copy suggests that Fresher may have still been making these guitars as non-effector reproductions at this time.

Perhaps even more interesting than the Built-in 5 Effects guitars were the Fresher Preamp guitars introduced in around 1978. These were equal double cutaway solidbodies with neck-through-body construction clearly in the same mode as other guitars popular at the time, including the Ibanez Musician and Aria Pro II Rev-Sound, all inspired by the success and aesthetics of Alembic.

Two Fresher Preamp guitars were offered, the FX-309G and the FX-509. Both had wide shallow cutaways, almost perpendicular to the two-octave neck, with sharp little points on the horns. The neck was a five-ply maple-walnut laminate ending in a dramatically tapered three-and-three headstock, almost like a Paul Reed Smith, with a large concave scoop out of the top, the upper edge extending beyond the lower. The nut was brass. The fingerboard was bound and possibly made of an ebonized maple, if the copy is to be believed (or understood), inlaid with large oval position markers. Two twelve-pole humbuckers were mounted on metal surrounds. The stud-mounted bridge/tailpiece assembly was finetunable and had those little set-screws in the back to let you adjust them further. A brass sustain block was mounted in the body under the bridge. Hardware was gold. The FX-309G had one rotary pickup selector on the upper horn, while the FX-509 added a second rotary selector on the lower horn, yielding “18 settings.” These had white ash bodies which could be finished in natural oak or a two-tone light and dark color combination.

Here’s what the copy said about the electronics. “The ultimate for Tone Variation. Fresher Preamp guitars offer the greatest variety of tone variations available today.

“Using an On-Board Equalizer Preamp system, the player can control a wide range of Treble, Middle, and Bass sensitivities independently. And there rich tone variations can be controlled with out high frequency loss.”

Basically the controls were four knobs set along a metal Tele-like strip on the lower bout and included a master volume, treble, middle and bass tone controls. The preamp was operated by two 9-volt batteries.

Both the Built-in 5 Effects and Preamp guitars were offered in the United Kingdom in 1978 carrying the Kimbara brand name. The Effect line included the Kimbara 181/V Les Paul copy and the Kimbara 183/Y Strat with vibrato. This latter had the maple ‘board and the headstock simply read “Kimbara” with no faux-Stratocaster “Straighter” to confuse the issue. The Kimbara 183/B was basically a dark natural finished version of the FX-509.

At least seven other guitars were offered in the Fresher line in around 1978 or so, several of which are quite curious, as well. These were essentially “copies,” but some took liberties with their inspirations.

The EX-670 was a pretty faithful copy of a Gibson Explorer, with a glued-in neck and appointments essentially the same as the original. The SL-380 was a copy of a Gibson Thunderbird bass. The FS-556N was basically a Strat copy with a natural ash body, with Fender-style head, maple ‘board, traditional vibrato and pickguard with three single-coil pickups. What was different was the neck, which stretched all the way through the body with a heelless neck joint.

Also offered was the BM-270 which was a copy of Brian May’s famous potato-shaped guitar. This had three pickups and was a dead ringer for the original. There was no date on this catalog, so I’ve assumed a late Seventies date. Even if it’s slightly later, this copy of May’s guitar appears to predate May’s arrangement with Guild.

Also curious was the FX-840, which was a pretty good copy of the Ibanez Artist model. This had the twin small double cutaway horns, twin humbuckers, and a glued-in neck with a bound fingerboard with trapezoid inlays. The only difference was a three-and-three headstock with a flared crown.

Two other strange hybrid guitars were offered. The FW-810 was an offset double cutaway with a body very similar to the Ibanez Studio series, which also dated from 1978. This had a pair of humbuckers attached to a six-position rotary select on the upper horn. This had a tapered headstock with an asymmetrical concave scoop out of the top, basically the same as on the Pre-Amp guitar, and not unlike the Ibanez Artist headstock. The FY-820 was an odd bass which had an exaggerated ash Fender P-Bass shape with a single split-coil pickup, a goofy batwing pickguard under the strings, maple fingerboard, and a neck that ended in a Firebird/Thunderbird headstock!

In the early Eighties Fresher introduced another wonderful guitars which it advertised as being designed for the year 2001, the FX-700. This was a very angular Explorer with sharp points at each angle. It was done up in black with natty red binding, including on the fingerboard, which also had red dots. This had a locking vibrato system that looked like a Kahler and a pair of humbuckers with exposed staple pole pieces, threeway, volume and tone.

At least two other Strat variations were available in the early Eighties as well, the FS-380S and FS-380H, the former with single-coils, the latter with a pair of humbuckers. This had a pickguard, and the humbuckers were covered in black plastic, with no poles visible. Hardware was black, with a traditional vibrato.

At least one bass from this later era was offered, the FSP-850. This looked remarkably like a Riverhead Jupiter, with a rounded crown on the two-and-two head, a slim, offset double cutaway body with an extended round upper horn and an outwardly flared thinner lower horn. This had two single-coil pickups, threeway and two volumes and two tones.

Clearly, these were not the only guitars offered by Fresher toward the end, but these are the only ones I’ve seen, and those were in photographs only.

The Kyowa Company stopped producing Fresher guitars in 1985, and thus ends our brief saga. If you know more about this obscure Japanese brand, I’d welcome the information. But, at least now you know something the next time you encounter a Fresher Straighter with Built-In 5 Effects! Thanks to Nils Freiberger and Michael Lee Allen for giving us the opportunity to explore as much as we have.

Ca. 1978 Fresher Straighter Strat copy with the Built-In 5 Effects.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Sep. ’95 issue.