-

Wolf Marshall

Fretprints: Larry Carlton

Revisiting Room 335

In 1978, Larry Carlton was atop the unforgiving environs of L.A.’s music studios, where technical prowess, precision, creativity, tone, and groove are minimum requirements and mere competence promises a short work day. Carlton’s grasp of myriad styles, inventiveness, versatility, inimitable phrasing, distinctive sound, and taste ingratiated him to discriminating artists, producers, and band leaders in

-

Wolf Marshall

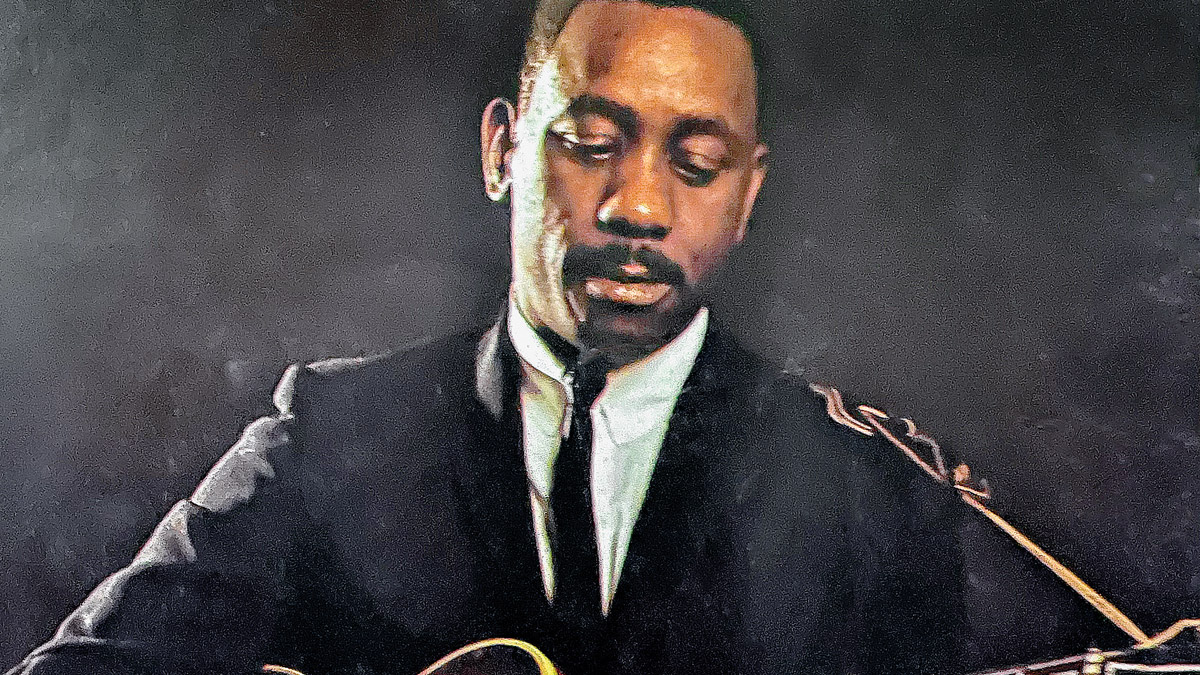

Fretprints: Wes Montgomery

Full House: Transcendent Jazz Masterpiece

Wes Montgomery is an iconic guitarist – a titan in the jazz genre. Boasting a style as unique and inimitable as Django Reinhardt or Jimi Hendrix, he burst upon the scene in 1960 and immediately redefined the sound and attitude of modern jazz guitar. Montgomery’s records for the Riverside label inspired countless musicians before he

-

Wolf Marshall

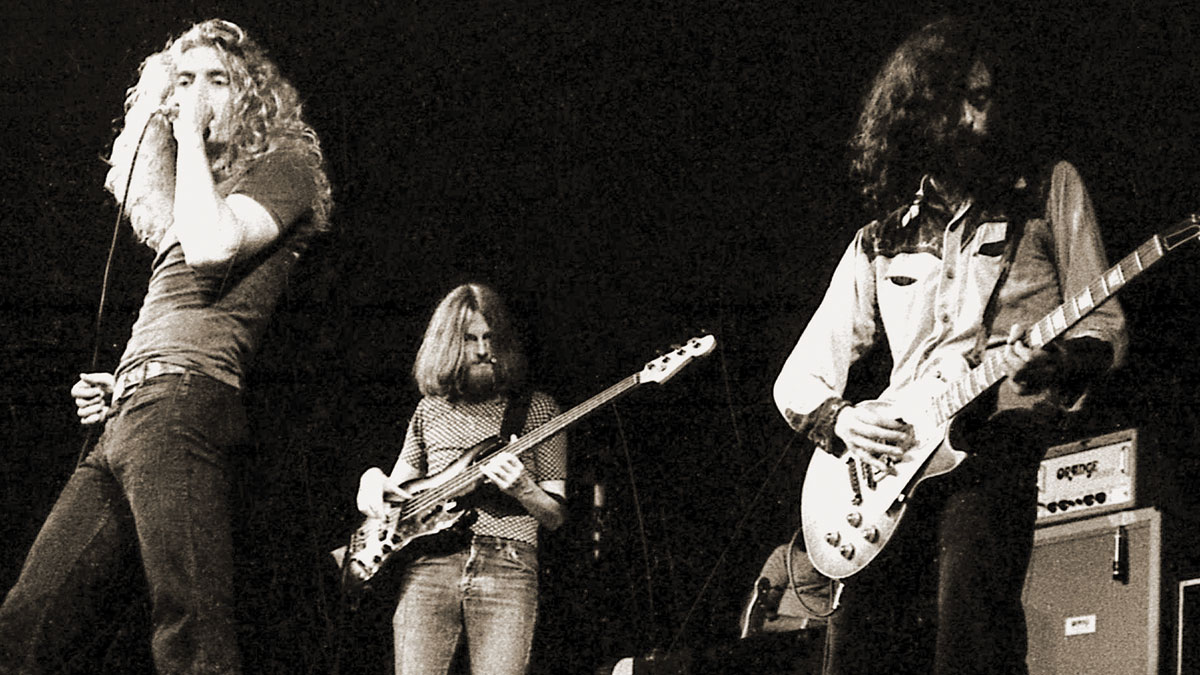

Fretprints: Led Zeppelin

One of the truly classic rock albums, Led Zeppelin’s IV brought together the band’s towering advances achieved with its first three releases. An extraordinary amalgam of blues-rock, progressive aspirations, heavy-metal antecedents, lingering psychedelic overtones, uncommon acoustic colorations, and imaginative orchestration, it remains iconic. Taking cues from – but surpassing – the second wave of the

-

Wolf Marshall

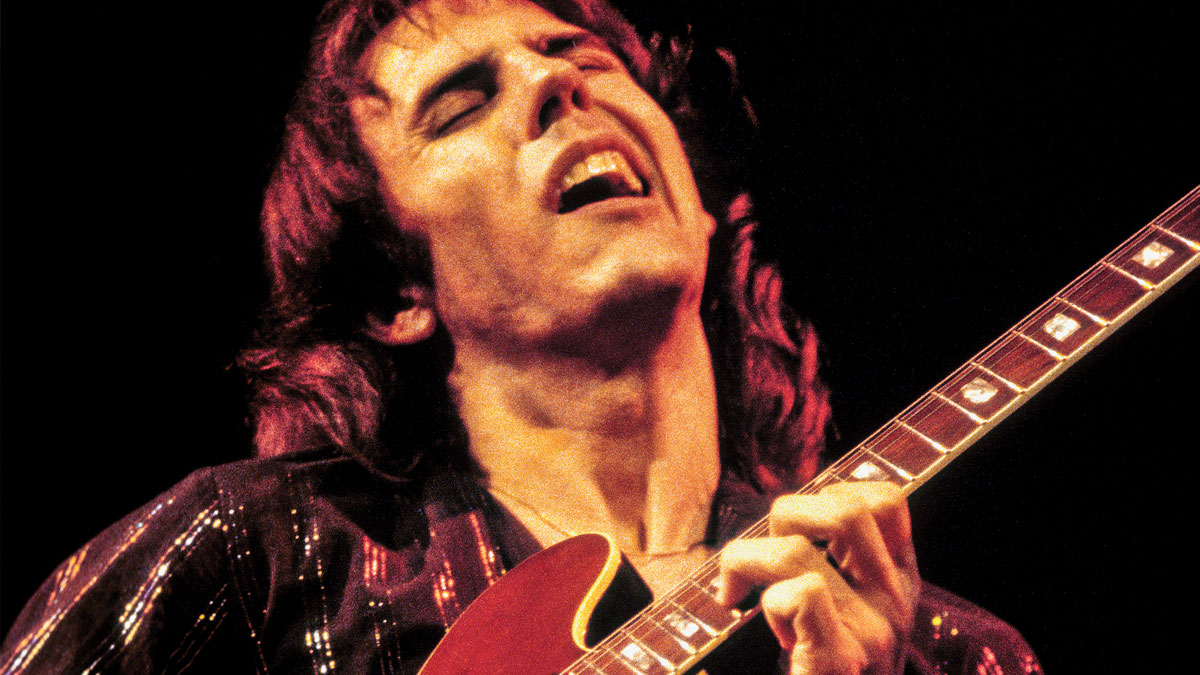

Fretprints: Gary Moore’s Still Got the Blues

Defining Document

Throughout his career, Gary Moore was haunted by a prevailing assumption (in rock circles) that he was simply too good to gain mass popularity. An accomplished, soulful vocalist and genuine guitarist’s guitarist, his versatility and technical mastery enabled him to move effortlessly from blues, rock, and power pop to metal, techno, hard rock, fusion, and

-

Wolf Marshall

Fretprints: Metallica’s Master of Puppets

Genre Giant

In 1984, Kerrang magazine coined the buzzword “thrash,” signaling the arrival of an unprecedented heaviness in rock music – not only in volume and aggression, but precision, velocity, complexity, and social messaging. Alongside fellow seminal thrashers Megadeth, Anthrax, and Slayer, Metallica represented the zenith of the form’s evolution, personified by larger-than-life sonics and challenging commentary

-

Wolf Marshall

Fretprints: Stevie Ray Vaughan

Texas Flood

Stevie Ray Vaughan was unknown when he premiered at the 1982 Montreux Jazz Festival. Born and bred in Dallas, he’d played the Texas bar circuit as sideman in Blackbird, the Nightcrawlers, Cobras, and Triple Threat Revue before becoming a local phenom as frontman of Double Trouble. Formed with bassist Jackie Newhouse and drummer Chris Layton

-

Wolf Marshall

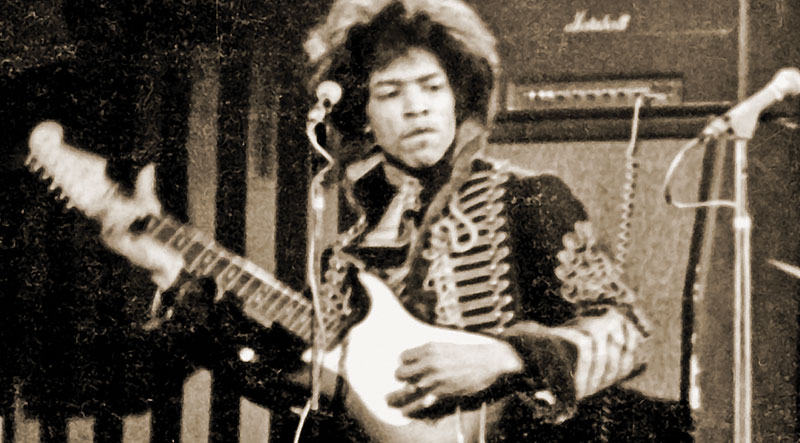

Fretprints: Jimi Hendrix

The Creation of Are You Experienced?

It was a bio-pic fantasy. The scene: Outside a London venue where Jimi Hendrix is performing for the first time. Leaving the club, Pete Townshend encounters Jeff Beck, just arriving. Beck asks, “Is he that bad?” Townshend replies, “No, he’s that good!” Springing from America’s R&B landscape, Jimi Hendrix was indeed that good; the real

-

Wolf Marshall

Fretprints: Elvis Presley

Sun Sessions and the Birth of Rock and Roll

History has it that rock and roll materialized in the wee hours of July 6, 1954, when a painfully introverted teenager suddenly grabbed his guitar during a fruitless Sun Records audition, cut loose, and, according to guitarist Scotty Moore, started “singing this song, jumping around and acting the fool… Then, Bill (Black) picked up his

-

Wolf Marshall

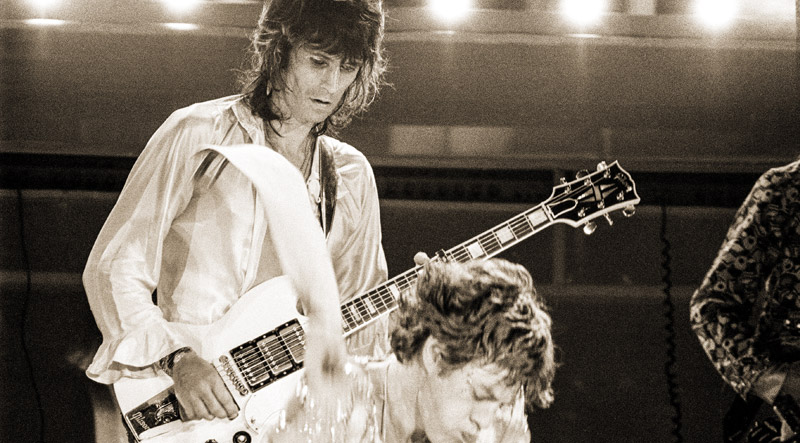

Fretprints: The Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street

Enigmatic, Artistic

Exile on Main Street is an album of enigma and mystery, a travelog through arcane (but familiar) soundscapes, and strong artistic statement. Considered the Rolling Stones’ greatest work of their most-creative period, it followed Beggars Banquet, Let It Bleed, and Sticky Fingers along with “Honky Tonk Women,” “Jumping Jack Flash,” and “Brown Sugar.” Exile completed

-

Wolf Marshall

Fretprints: Jeff Watson

Night Ranger, The Classic Years

Rock and roll in the 1980s saw styles collide after two decades of unbridled innovation. Night Ranger’s melodic-metal arena rock epitomized the period, but never fit a stereotype. With catchy commercial songs and power ballads, guitar antics and heavy power chords made it a great guitar-rock band that incorporated keyboards, tight arrangements, and hooks aided