-

Peter Stuart Kohman

Vivi-Tone “Skeleton

A Master’s Magnificent Misfire

The eternal question “Who invented the electric guitar?” has no single answer. By the late 1920s, many players, tinkerers, and inventors were exploring ways to get more volume from fretted instruments. Steel-string flat-tops from Martin, f-hole archtops from Gibson, and metal-bodied resonators from National were louder than their predecessors, but ran up against physical limits.

-

Peter Stuart Kohman

Weymann Model 890 Jimmie Rodgers Special

Hey Hey, Tell ’Em About US

Jimmie Rodgers has been called many things; while active from 1927-’33 he was billed as “the Singing Brakeman” and ”America’s Blue Yodeler” but, in the decades since, the “Father of Country Music” has become most apt. Rodgers’ popularity on record was practically unmatched during his sadly brief career, and a great majority of country artists

-

Peter Stuart Kohman

The (Way) Back Beat: Top O’ The Line, For Only $150!

The Immortal Danelectro Guitarlin

Having looked at the most expensive electric guitars offered in 1960s – over 50 years ago. Traditional makers – Gibson, Guild, and Gretsch – concentrated on flashy amplified archtops that retailed up into the $700 to $800 range – beautiful instruments, but not representative of where the electric guitar was going. More forward-looking makers offered

-

Peter Stuart Kohman

Ca. 1960 Custom Mosrite/Gretsch

A Bakersfield/Brooklyn Cowboy

In the history of vintage guitars, Gretsch and Mosrite are sometimes linked, and often associated with ’50s hot-country pickers and ’60s rockers. One guitar takes that connection to a new level. This custom Mosrite hollowbody has the chassis of an early Gretsch Country Gentleman and was likely built between 1959 and ’62 for a hotshot

-

Peter Stuart Kohman

Name that Twang

The Guild-Duane Eddy Connection

The fledgling Guild company scored a coup when it signed Johnny Smith to an endorsement deal in 1956. Perched atop the jazz-guitar scene at the time, Smith helped Guild join the fray of artist “signature” instruments that had become a marketing staple. Unfortunately, the effort sputtered because Smith was not pleased with the guitar bearing

-

Peter Stuart Kohman

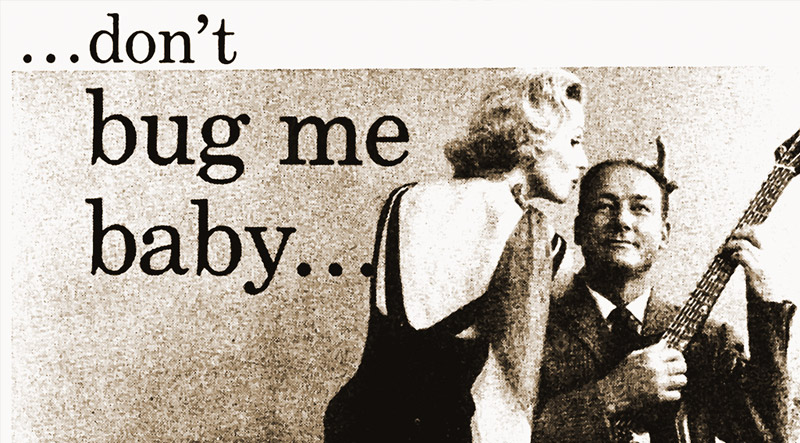

The (Way) Back Beat: A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody

Fretted cheesecake advertising through the years, Part One

There are many ways for an advertiser to attract attention, and in the history of 19th- and 20th-century print hucksterisim there have been few stones left unturned in the battle for audience eyes! If the intended demographic is largely male, one of the most reliable strategies is to place a pretty girl next to –

-

Peter Stuart Kohman

The (Way) Back Beat: A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody

Fretted cheesecake advertising through the years, Part 3: The 1960s

Fretted-instrument advertising in the 20th century relied heavily on “glamor” or “cheesecake.” Electric instruments and accessories, in particular, are still marketed to a primarily male audience, and with that testosterone target comes a temptation to go the sexy (some would say sexist) route. This marketing approach has a long history, waxing and waning but never

-

Peter Stuart Kohman

The (Way) Back Beat: A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody

Fretted cheesecake advertising through the years, Part Two

Last month, we began looking at some of the more entertaining fretted instrument advertising of the 20th century, in what could be loosely called the “cheesecake” style! This term generally refers to the gratuitous – or at least technically questionable – use of female charms to get a reader’s attention. Over the years, the popularity

-

Peter Stuart Kohman

In Memoriam: John Teagle

Guitarist, historian, and author John Teagle passed away March 26 in New York at age 66 after battling cancer. Teagle recalled being “Born at the height of the original rock-and-roll era” in Akron, Ohio, and came of age in the late ’70s/early ’80s “Akron Sound” era, working in music shops and venues, including running sound

-

Peter Stuart Kohman

Gibson’s “Non-Reverse” Firebirds

When Down Was Up

Some guitars get no respect, at least historically. At the dawn of the ’70s, Gibson’s original (1963-’65) Firebirds were already being hailed as classics, while the versions that replaced them were denigrated as another example of the company’s late-’60s decline. Second-generation Firebirds are often cited as being “post-McCarty,” but the fact is Gibson president Ted