The story of Mossman guitars is one of both tragedy and triumph. Often forgotten in the rejuvenated interest with acoustic guitars of the 1990s, Mossmans are best known for their craftsmanship, high-quality tonewoods, and attention to detail from a period when major manufacturers were rushing to meet the demand for acoustic guitars. While many of those instruments made during the high-production ’70s by volume manufacturers are now reviled by collectors, Mossman guitars from the period are exceptional in design, materials, and construction.

History

Stuart Mossman began making guitars in 1965, his early efforts concentrated on experimentation with bracing of the tops. He spent four years building 40 or 50 prototypes in his garage. By the end of the decade, sensing a niche in the market for high-quality handmade acoustics, he had incorporated S. L. Mossman Guitars in Winfield, Kansas, and moved into facilities at Strother’s Field, outside of town. Mossman noticed what was happening with major acoustic guitar manufacturers at the time; the folk music boom had pushed demand for acoustic instruments to an all-time high, and while Gibson, Martin and Guild were increasing production, imports from the Pacific rim countries were beginning to exploit the lower end of the market.

Mossman was concerned with what he saw as an erosion in materials, design, and craftsmanship in the construction of the traditional flat-top acoustic guitar, particularly among the larger manufacturers as they rushed to meet the strong demand. Using only top-quality woods, a proprietary bracing structure, and old world building techniques, Mossman guitars entered series production in 1970.

“We were the first of the small manufacturers to make it as a larger company,” Stuart Mossman recalls. “We made some fine guitars and I’m pleased so many are still being played and enjoyed.”

Mossman sales literature from the early period made no mistake about lowered quality amongst the large builders and the use of laminated woods:

“We at Mossman are disgusted with what has happened to the quality of goods produced in this country. Quality has been sacrificed for quantity. Mass production has gotten out of hand. Craft has almost been completely eliminated from our society. This vile abomination [of plywood] is currently being perpetuated on the unsuspecting guitar playing public on a grand scale. We at Mossman considered plywood briefly one day and unanimously decided that plywood makes the best cement forms available. We do not now nor will we ever stoop to the level of plywood construction, and we apologize for our contemporaries who have lowered the station of our craft by using laminated backs and sides. Mossman considers itself a happy exception to the current trend. We are relatively small and our able to devote all our energies to quality craftsmanship and the selection of fine aged woods. We love making guitars and are proud of our work.”

Model Lineup

The company specialized in production of dreadnought-sized guitars, likely due to Mossman’s background as a flatpicker, and offered four basic models at the beginning. All featured Sitka spruce top, Grover Rotomatic tuners, 25 3/4-inch scale length, and ebony fingerboard and bridge except where noted. An early catalog from 1972 shows the following models:

Tennessee Flat Top was constructed with mahogany back and sides, rosewood fingerboard and bridge, dot inlay, and black plastic binding on top and back of body. Suggested retail $350 in 1972.

Flint Hills used East Indian Rosewood back and sides with white plastic binding and herringbone inlay around soundhole, $450 retail. Also available was the Flint Hills Custom, which featured bound neck and peghead, abalone snowflake position markers, abalone inlay around body perimeter and soundhole, and gold Grovers, for $650.

Great Plains was essentially the Flint Hills with Brazilian rosewood back and sides, and herringbone inlay around the body perimeter, $525. The Great Plains Custom offered the addition of bound neck and peghead, gold Grovers, and abalone binding, $725.

Golden Era was Mossman’s top-line instrument and featured select Brazilian rosewood back and sides, German spruce top, abalone inlay around the top, three-piece back with abalone back strip inlay, bound neck and headstock, gold Grovers, and an intricate abalone vine inlay up the length of the fingerboard. Suggested retail was $875. A Golden Era Custom added an advanced Maurer abalone inlay on the neck and headstock.

Mossman offered a variety of options on any model, such as extra-wide neck and 12 strings, and also provided custom inlay and engraving work. In fact, a customer could order any sort of special voicing for a new Mossman (described in the catalog as “overbalanced bass, overbalanced treble, or balanced bass and treble”) and by careful shaving of the braces during construction and assembly, either the top or bottom end could be emphasized.

The guitars were made to take medium-gauge strings, and all had the same distinctively-shaped tortoise pickguard. The neck measures 1 11/16″ at the nut and is rather thin in profile, providing fast fretwork and ease of picking, but does have an adjustable truss rod accessible through the soundhole. Mossman used a radical (for the time) bolt-on neck arrangement with a mortise-and-tenon joint which was bolted and glued to the neck. A cover on the neck block hides the bolt ends. Final neck size and shape was achieved because the man at the factory who carved the necks was a banjo player and he liked the feel and playability of lower-profile necks!

Comparison with the contemporary Martin-built dreadnought is enlightening, since this guitar represents the standard to which others are held. The two were close competitors, price-wise, but Mossman had a slight advantage, averaging about a 10 percent lower retail price than Martin, for comparable models. Both produced fine guitars with top-quality tonewoods, offered lifetime warranties to the original owner, and were considered professional-grade instruments. But by the early ’70s, Martin had increased production to a nearly 20,000 instruments annually, more than 20 times the rate Mossman achieved.

While the Martin factory was simply trying to meet demand for its product, Mossman never wanted to build on such a scale.

“I personally inspected each guitar we made, before shipment,” he said. “Eight to 10 per day is as many as we would ever want to make, because it would be difficult to personally inspect more.”

Still, by 1974, Mossman had expanded his facilities to account for increased sales and production that had more than doubled in each of the preceding years. Sales literature from the period shows the same four basic models, but all had been refined and upgraded. The Tennessee Flat Top now featured a red and amber wood inlay around the perimeter of the body and soundhole. The Flint Hills had a similar brown and white perimeter and soundhole inlay, while the Flint Hills Custom had abalone perimeter inlay and snowflake position markers on the fingerboard. The Great Plains model retained its herringbone binding while the Great Plains Custom had abalone perimeter inlay and a new mother of pearl vine and flower inlay over the entire fingerboard. The Golden Era continued and incorporated most of the features of the Golden Era Custom, which was deleted. The back of the 1974 catalog is a full-page color poster of the Mossman Golden Era in all its splendor.

Fire!

In early 1975, while the Mossman company was producing nearly 100 guitars per month, including a line of six production models and custom order instruments, disaster struck.

A fire in the finishing area destroyed one of the buildings housing the manufacturing area and assembly line. No one was killed and losses to machinery were minimal. Only a few guitars were lost, but the company’s complete supply of Brazilian rosewood, the only wood stock stored in that location, was destroyed.

Production continued and a Small Business Administration loan (acquired for expansion before the fire) of $400,000 was used to build and expand the production facilities. Hoping the worst was behind him, and with an eye toward maintaining his employees and capitalizing on demand for his guitars, Mossman entered into a distribution agreement with the C.G. Conn company to get guitars to dealers across the country and overseas. Mossman had been spending much time in sales, and he employed a group of salespeople who took orders and sold guitars to dealers. But the new arrangement promised to greatly improve delivery of finished instruments. Conn had both the distributorship experience and the network of dealers already built up with lower-line imported guitars and was ready to work at higher price points. It appeared the two could provide complementary resources.

Production was increased to about 150 instruments per month and the line of standard models was increased to seven six-string and two 12-string models, as described in the 1976 product catalog. All models, except the Tennessee Flat Top, with its mahogany body, used Indian rosewood, since the stock of Brazilian burned. Retail prices did not include hardshell case for an extra $100.

Tennessee Flat Top continued as previously described but now with ebony fingerboard, nut, and bridge. Retail $625. Twelve-string available at $695 retail.

Flint Hills continued as previously described. Retail $725. The Flint Hills Custom was dropped.

Great Plains continued with the addition of a three-piece back. Retail $860. Great Plains Custom was dropped.

Timber Creek was a new model with three-piece back and snowflake position markers. Had distinctive brown, black, and white wood inlay pattern. Retail $1,095.

Winter Wheat, another new model, was the same as the previously offered Flint Hills Custom and had abalone inlay on body perimeter with snowflake fingerboard markers. Retail $1,295. Winter Wheat also offered in 12-string, for $1,345.

South Wind was yet another new model and was essentially the previously-offered Great Plains Custom, featuring abalone inlay around the body and the mother of pearl vine-and-flower inlay on the fingerboard. Retail $1,595.

Golden Era remained the top-line model and now the gold Grovers had buttons engraved with a stylized “M.” Headstock was inlaid with the floral M and the S.L. Mossman decal on the back of the headstock. Retail $2,095.

“Conn”ed

In conjunction with Conn, Mossman took full-page color ads in Guitar Player and other guitar magazines, showing the Golden Era guitar and mentioning a catalog available for $1. The catalog consisted of a color portfolio with individual color sheets on each model, and was drenched in the spirit evoked by the wild prairie and the old west.

Production was accelerated and by 1977, Conn had amassed a stock of 1,200 guitars for distribution. They were stored in a warehouse in Nevada when, alas, tragedy struck again. The storage warehouse used by Conn had minimal controls for heat and humidity and they had experienced no problems with cheaper laminated guitars stored there previously. But it was a different story with carefully-made solid wood Mossman guitars. Baked during the day, then frozen at night, finishes checked badly and/or bodies cracked. For a company that built its reputation on high quality, it was a devastating blow.

A disagreement arose between Mossman and Conn about responsibility for the disaster and compensation for damage. Conn withheld payment for instruments already purchased and refused to take delivery of those already ordered. A lawsuit finally settled the matter, but cash flow problems brought by the disagreement forced Mossman to lay off most of his staff.

By 1979, the company was down to just a few people producing a small number of instruments per month, and the model line was trimmed. The Tennessee Flat Top was dropped first, then the Winter Wheat and South Wind, and the twelve-string models were all dropped, leaving the offerings on the 1979 price list as the Flint Hills for $795, Great Plains for $895, Timber Creek at $1,150, and Golden Era for $1,695, all suggested retail.

Mossman was also selling off two to three-year-old guitars which had been part of the group cosmetically damaged by the Conn incident. These were in essence competing with the new models and they were sold at a considerable savings over original retail prices. Mossman no longer had the extensive retail distribution needed to sustain large-scale production and the sale of weather checked instruments brought in much needed cash. New guitars were being produced at a trickle.

Mossman continued to build guitars at this rate through the early 1980s, never again achieving production levels of the mid ’70s. This was a difficult time for the guitar business in general and the acoustic guitar business in particular, as musicians turned to keyboards and synthesizers. Mossman’s health was being affected by years of breathing sawdust, lacquer fumes, and abalone shell fragments.

He was considering selling the company, when a former employee named Scott Baxendale offered to buy the company name, inventory, and equipment. Mossman sold the company to Baxendale in 1986, but not before a final buildout of some 25 extraordinary guitars. Using the finest woods that had been set aside for years, Mossman crafted a series of superlative guitars, not so much for resale, but because it was a chance to bring together all his experience with the choicest woods. These “final 25” guitars have become the source of popular folklore. A few have occasionally turned up for sale, but Mossman still owns many of them.

A New Beginning

Baxendale’s ownership of the Mossman company was short-lived. In the late 1980s, he moved the company to Dallas and built a series of high-end one-off guitars, including the Mossman Superlative, pictured in Gruhn and Carter’s Acoustic Guitars and Other Fretted Instruments. This guitar is as superlative as the name implies, with incredibly ornate and detailed inlay work covering much of the body and head. In 1989, Baxendale sold the company to John Kinsey and Bob Casey.

“We bought the company because of the history and reputation Mossman established, and because we felt it was a real opportunity,” Kinsey said.

In 1991, Mossman Guitars was moved to Sulphur Springs, Texas, where it continues to this day. The current catalog lists these models:

Texas Plains is essentially the Great Plains model with herringbone inlay, renamed to reflect the Texas production site. Available in mahogany and rosewood.

Lone Star is a mahogany bodied guitar which features an aged mahogany back, sides, and neck using which was salvaged from the Lone Star Steel Company in Texas. It has a star inlay in the first fret and white plastic binding.

Winter Wheat continues as before with abalone inlay around the body.

South Wind continues as before with the mother of pearl vine and flower inlay on fretboard at.

Golden Era, the Mossman guitar, also continues as before with top-line features including intricate abalone inlay on top and fingerboard.

Kinsey and Casey brought years of guitar repair and construction experience to the enterprise and have developed a new suspension bracing system for their Mossman guitars. In this system, a traditional X-bracing (with two tone bars) is used, but instead of scalloping the braces, each has a series of elongated holes cut into them, which reduces the mass of the brace, but maintains the strength. The suspension bracing system “…gives you all of the punch at the bottom end, without the boom,” says Kinsey. These new Mossman guitars are made to order with a two to three-month waiting time and sound as good as any Mossman.

A Fine Flatpicker

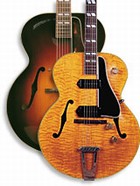

Mossman guitars have always been highly respected by players. While it would be inaccurate to call these Martin copies, they were traditional dreadnought-shaped acoustics with solid spruce tops and either mahogany or rosewood backs and sides. A key feature of the Mossman guitar was handcrafting, which is evident in all components of the instrument, from bracing and inlay to final finishing. The commitment to craftsmanship and individual taste in guitar building set the Mossman apart from other large-scale manufacturers of the period and gave the instruments a unique sound. For example, one of the hallmarks of the top-line Golden Era guitar was its intricate inlay. Of particular interest is the vine inlay on the fingerboard, which recalls similar inlays on classic instruments by Washburn and Maurer.

While the influence is clear, the Mossman design is unique. Stu Mossman spent countless hours perfecting this vine inlay for the longer fretboard of the dreadnought body and its 25 3/4″ scale length. Early Maurers and Washburns were parlor guitars roughly “0” size with shorter scale lengths and fingerboards, so proper inlay patterns were developed specifically for the Golden Era guitar. At the time, no one offered this level of ornateness.

One of the better-known early Mossman enthusiasts is flatpicker Dan Crary, now a Taylor endorser with his own signature model. Crary played a Mossman for years, and was featured on the cover of Frets Magazine in February, 1980, holding his Mossman Great Plains. In the interview, Crary was asked specifically about his Mossman.

“The current Mossman Great Plains Model I play exceeds my ’56 (Martin) D-28, which I think very highly of,” he said. “But in the case of the Mossman I own now, I have never owned a guitar that is equal to it, and it’s less than two years old.”

Other high-profile Mossman users – there were never any paid endorsements – included John Denver, Emmylou Harris, Hank Snow, Cat Stevens, and Merle Travis. Mossman also sold several guitars to his Hollywood friends Keith and Bobby Carradine and other well-known actors. New Mossman guitars have also been well-received by country and bluegrass performers. Texas cowboy musician Red Steegal plays a new one, as does country/western guitarist Clay Walker.

Serial Numbers and Identification

Early Mossman guitars feature the S.L. Mossman name at the top of the headstock in gold gothic script on a decal, except for the inlayed models, where it is usually found on the back of the headstock. In 1978, Mossman changed the logo to a modern graphic with a larger, rounded S in order to differentiate them from the models made for Conn and subsequently damaged. More recently, Mossman guitars have an outline of the state of Texas in the larger loop of the S.

In addition, the model designations given to early Mossmans were not reflected on the labels inside the soundhole, so it is often necessary to compare them to the catalog descriptions. Model names began showing up on labels about 1974. These early labels were either white or brown and bear the legend “S.L. Mossman Handmade Guitars.”

In 1970, a plain white paper label with black gothic printing reading “S.L. Mossman, Winfield KS” was standardized. The label changed again in 1986, to reflect the change of ownership. The label was still white, but had blue printing and at the bottom reads “Baxendale Enterprises.” The outline of the state of Texas was added to the larger loop of the S on the label during this time.

Current Mossman guitars built in Sulphur Springs have a white label on the coverplate of the neckblock (inside the soundhole) which lists model name, serial number and date of manufacture. Guitars built prior to 1970 have a letter denoting body style (most were D, for dreadnought) and are numbered sequentially.

“Somewhere out there is a Mossman D-28,” Stuart Mossman laughs.

About 250 guitars were made between 1965 and 1970. In ’70, the letter prefix was dropped and two digits were added in front of the serial number denoting the year of manufacture. 73-957 would have been produced in 1973 and would be the 957th guitar produced overall. Baxendale continued this numbering system, but it was replaced by Kinsey and Casey with a new code. For newly-produced Mossman guitars, the serial number code is year and month of manufacture followed by the instrument’s position in that month. For example, 97034 would be the fourth guitar built in March of 1997.

One of the hallmarks of the Mossman guitar is the paper label bearing the number and model was always signed or initialed by the craftsmen. Besides its interest as a detail, this fact helps in judging the relative size of the shop at any given time. For example, a 1973 model shows five names on the label, a 1976 model has 22 sets of initials, a 1979 model has only two names, and a 1985 model three names. Comparing a guitar made in ’73 with serial number 73-342 and a 1976 model with the number 76-4613 shows just how fast the company grew and increased production during those years. The signed label tradition was dropped for a period after Kinsey and Casey bought the company, but as of January 1997, it was reinstituted. The three signatures are those of builders John Kinsey, Bob Casey, and Marie Casey, who handles all the delicate inlay work.

Collectible?

The original Mossman company produced about 7,500 guitars. Of these, Stu Mossman says the rarest is the South Wind model, produced from 1976 to ’78. Any of the 12-strings are also comparatively rare, and there are also numerous custom-ordered or one-of-a-kind guitars such as the maple-bodied sunburst finish instrument featured in the December 1996 issue of VG Classics. A full 10 percent of production (about 750 guitars) was the popular and fancy Golden Era model. Cases for the original Mossmans were supplied by the S&S Company of Brooklyn, New York, and are good quality five-ply wood cases with a black vinyl covering.

Baxendale-produced instruments are comparatively rare, only 100 or so were built, and recent Mossman guitars made in Sulphur Springs, Texas, are produced at a rate of only 50 instruments per year. Collectors and guitar show attendees will most commonly encounter instruments made from 1974-’76, when production was at its peak, and a good percentage of these will show the cold weather checking pattern associated with the Conn debacle. Be aware that in most cases, this is an aesthetic concern only and does not imply structural damage. These guitars generally play and sound as good as any Mossmans. Nearly any properly set up Mossman dreadnought sounds fine, with crisp highs, deep bass, and good balance across the strings. True collectors will want to look for early high-end models with Brazilian rosewood construction and intricate inlay, but these can be hard to find. Rarely do the fancy custom models come up for sale and they are generally snapped up by knowledgeable buyers.

Mossman dreadnoughts have no real quirks. Construction is solid and with proper care, necks don’t warp and tops don’t belly. Some might say they are overbraced, but they were made for medium-gauge strings and a hard flatpicking style. Thus, many players have related that Mossmans are very responsive to fingerpicking. It is not uncommon to find a nice Mossman dreadnought in excellent condition. Pricing for vintage models varies depending on wood choice, condition, and ornamentation. A serviceable lower-end model can be had for as little as $600. Instruments with body or neck inlay will be around $1,500 for examples in excellent condition. The Golden Era seems frozen in time with a typical asking price of $2,500. Note that Brazilian rosewood on any model will add to the price and, of course, mint condition means a higher price. Values can, of course, vary depending on the dealer. But by any measure, a used Mossman at these prices offers excellent value for the money in a used, handmade guitar.

I Coulda’ Been a Contender

The 1990s emphasis on quality of product extolled by Martin, Gibson, Taylor and other manufacturers is the same as the Mossman philosophy of the ’70s: each guitar built of premium materials to exacting specifications. It appears that in many ways, the original Mossman company was 20 years ahead of its time, and but for unavoidable tragedy, the company might today be a large, prosperous organization.

It is ironic that much of the attraction of certain model guitars in the late 1990s are elements of the original Mossman design. Taylor guitars are known for their thin, fast necks and revolutionary bolt-on neck attachment. But Mossman offered a similar-feeling neck beginning in the early ’70s, and has always used a bolt-on neck system. The recent surge in popularity of Larrivee guitars is in part due to their excellent sound, elaborate inlay and eye appeal. Ironically, Mossman inlay work was also high-quality and quite beautiful, at a time when no other volume builders were taking the time to decorate their bodies and fretboards in the traditional style.

The brilliant sparkle of abalone around the perimeter of the Mossman Golden Era is as fine as any Martin and the intricate inlay pattern on the fingerboard was accomplished long before computer-controlled milling machines. All Mossman inlay was done by hand and provides a state of grace not normally found in today’s offerings. The Mossman name lives on, as previously mentioned, at a small but dedicated factory in Texas, still offering a unique blend of old world craftsmanship with modern construction and materials. The original Mossman guitars should be remembered for a special attention to detail, for quality unavailable from the larger producers of the time, and for a sound and playability which today remains in the nicely-aged examples available on the used and collectible market.

Special thanks to Stuart Mossman, John Southern, Steve Peck, John Kinsey, Stephen and Gus at Guitar Shop, and Randy Axelson. New Mossman guitars can be ordered at (903) 885-4992.

Photo: John Southern

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Sept. ’97 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.