-

Cliff Hall

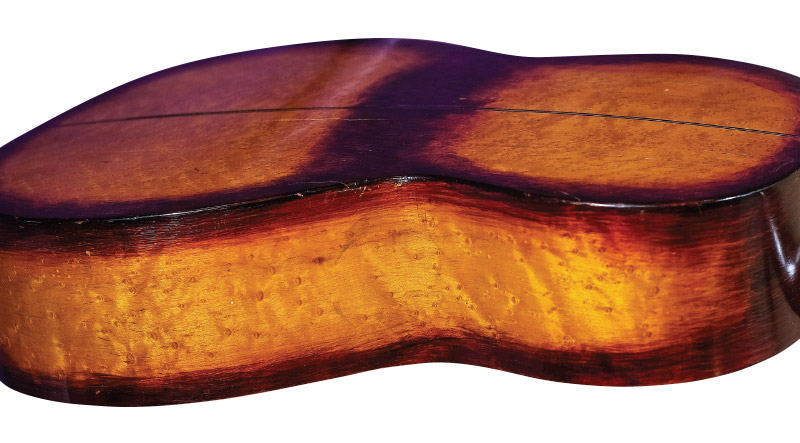

First to Sunburst

The Origin of a Famous Finish

Faced with anemic sales of its Les Paul Model in 1958, Gibson spiffed-up its goldtop with a sunburst finish in an attempt to outdo Fender’s two-toned Strat, rechristened it the “Les Paul Standard,” and hoped for the best. The old trick didn’t work, but the Kalamazoo company had been there before. Four decades prior, Gibson’s

-

Cliff Hall

The Guitars of Ernst Heinrich Roth

International Influence

Now just a sleepy town in Germany, over the last 200 years, Markneukirchen has been home to countless luthiers ranging from brilliant to brutish, and has exported millions of instruments all over the world. The city’s most-accomplished makers were Christian Frederick Martin and Ernst Heinrich Roth, and while Martin’s instruments are ubiquitous, it’s a well-hidden