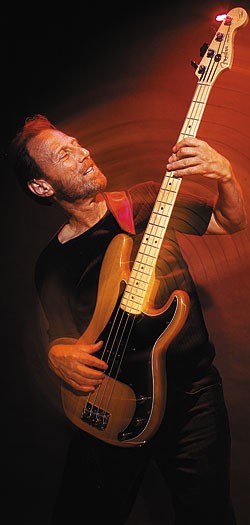

Rocco Prestia Photo: Neil Zlozower.

Bass great Jeff Berlin calls him “my all-time favorite groove player.” The equally formidable John Patitucci proclaims, “The guy has not only been a serious influence on most of today’s major-league players, he actually founded the damn league.” And no less than Nathan East marvels about bass lines “I could only hope to figure out and dream of someday being able to play.”

The man whose praises they and others have been singing for years is Francis “Rocco” Prestia, for most of the past 40 years bassist with soul ambassadors Tower Of Power.

In his award-winning book Standing In The Shadows Of Motown: The Life And Music Of Legendary Bassist James Jamerson, Allan “Dr. Licks” Slutsky declares, “The hardest working right hand in the bass business has to belong to [Prestia]. There has been a steady stream of staccato 16th notes and offbeat accents flowing out of the West Coast ever since he exploded on the pop music scene as a member of the Rolls Royce of funk bands, Tower Of Power. If you’ve ever tried to play any of Rocco’s bass parts, you have my sympathy. Your hands are probably just starting to uncramp. The technical demands of playing his lines from Tower Of Power songs like ‘Soul Vaccination,’ ‘You’ve Got To Funkifize,’ or ‘What Is Hip’ are overshadowed only by the creativity and originality of his melodic ideas and overall concept.”

The branch of rhythm and blues known as soul music is invariably subdivided according to regional schools – like Memphis, Philly, Muscle Shoals, “Northern Soul” in England, and of course the Motown sound of Detroit. San Francisco, on the other hand, was the incubator for ’60s psychedelia. Tower Of Power members would be quick to point out that they didn’t come from San Francisco; they cut their teeth in the East Bay, across the bridge, in Oakland. But the 10-piece, horn-laden funk machine benefited from the proximity, becoming regulars at the Fillmore Auditorium and eventually signing a management deal with the ballroom’s impresario, Bill Graham. Though the band’s 1970 debut, on Graham’s San Francisco label, failed to chart, its sound and title staked their claim in no uncertain terms: East Bay Grease.

By the time of its follow-up, 1972’s Bump City (Warner Bros.), tenor saxophonist and founder Emilio Castillo and baritone sax man Stephen “Funky Doctor” Kupka had established themselves as an impressive writing duo – co-writing the dance hit “Down To The Nightclub” with drummer David Garibaldi and penning the ballad “You’re Still A Young Man,” which penetrated the Top 40.

Soul icon (and Booker T. & The MGs guitarist) Steve Cropper produced the album. (For contractual reasons, engineer Ron Capone was credited as producer of the sophomore release, but Prestia concurs that Cropper produced it.) “Besides being a really fine musician and bass player who knows the instrument well,” Cropper says of Rocco, “he’s one of the better time-keepers on bass than anybody I ever worked with. His work with David Garibaldi – the tightness of his 16th notes and David’s kick drum – is phenomenal. It’s so clean and so precise. And they’re great entertainers as well; when you go see Tower Of Power, they I the tower of power!”

Prestia’s incessant, two-fingered, 16th-note approach is best illustrated on the aforementioned “What Is Hip?” from the band’s self-titled third album. A minor miracle of stamina, for starters, it drives the song’s jackhammer groove like few bass parts in the R&B canon.

The album, featuring singer Lenny White, also produced another funk workout (and Prestia tour de force), “Soul Vaccination,” and the ballad “So Very Hard To Go” – this time edging just below the Top 10, on both the Pop and R&B charts.

Despite numerous personnel changes (including five lead singers in the group’s first decade), Tower remained a force to be reckoned with. If the band wasn’t working (which was rare), the horn section was – their distinctive sound tapped at one time or another by headliners ranging from Rod Stewart to Huey Lewis, Santana, Aerosmith, and Elton John.

In ’77 Prestia got the axe, but Tower rehired him in ’84. His initial replacement in the interim was Victor Conte, more (in)famous today as the founder of Bay Area Laboratory Cooperative, or BALCO, which was involved in Major League Baseball’s steroid scandal.

In addition to solo projects by Tower alumni Bruce Conte and Mic Gillette and “Doc” Kupka’s splinter project, the Strokeland Superband, Prestia’s bass has graced albums by Percy Mayfield, Gov’t Mule, and others, and in 1999 he released a fine solo album, Everybody On The Bus (Lightyear), featuring former and current bandmates such as Garibaldi, guitarists Bruce Conte and Jeff Tamelier, and keyboardist Chester Thompson. Three tutorials have also been devoted to Prestia’s bass style: Francis Rocco Prestia Live At Bass Day DVD, filmed in ’98; Cherry Lane’s Play-It-Like-It-Is book/CD package, Sittin’ In With Rocco Prestia Of Tower Of Power; and his hard-to-find VHS course, Fingerstyle Funk.

In recent years, Prestia underwent heart valve replacement surgery and a liver transplant, but, still on tour with T.O.P., his playing shows no signs of slowing down.

In his Jamerson opus, author Slutsky paid Rocco perhaps the ultimate compliment. The book is half biography and half transcriptions of the Motown genius’ bass lines, with an accompanying CD featuring those parts played by bass giants from Jack Bruce to Geddy Lee to Anthony Jackson. Slutsky writes, “When Rocco handed in his tape of [the Contours’] ‘Just A Little Misunderstanding,’ he told me he never realized how deeply James Jamerson had affected his playing until he had to sit down and actually play one of his bass parts note for note. But the similarities in these two bassists run much deeper than just notes or rhythms. Both Jamerson and Rocco are the originators of unique schools of bass playing that have been copied all over the world… But just as there was only one James Jamerson, there is only one Francis ‘Rocco’ Prestia. There isn’t a bassist alive who sounds like either of them.”

Did you grow up in the East Bay?

Yeah, the band started in Fremont, and then we moved up to Oakland. I was in the original version of the band, in ’65, and we changed the name to Tower Of Power in ’68. Before that it was a few things – the Section Five, Black Orpheus, the Gotham City Crime Fighters, the Motowns.

Was it always funk and R&B?

No. There was always a touch of it, but we didn’t change over ’til mid ’67 and ’68. Started adding horns.

Before that, was it just rock and roll?

Not really rock and roll either. We did some soul tunes, and some Paul Revere & The Raiders, some Stones, the Animals, and stuff like that.

How old were you when you started playing bass?

Fourteen. Mimi [Emilio Castillo] and I went to high school together. He was a year ahead of me. He just wanted to form a band, so we did. They needed a guitar player, so I auditioned. Couldn’t play to save my life, but I had good hair, so they decided to keep me [laughs]. They said, “You can play bass, because you can’t play guitar.”

Mimi’s father knew this guy, Terry Saunders – jazz player out of the Bay Area – and he used to come in once a week and show us all the latest tunes, and show everybody their parts. That’s how we learned how to play.

What equipment were you using then?

My first bass was a Fender. I think it was a Precision. I played other basses, but that was the first rental bass that was brought and put in my hand.

I had a Silvertone guitar and amp I bought from Sears; 60 bucks for the set. But it was just one of those things; it just wasn’t in me to play guitar, for whatever reason.

When you switched to bass, did you adapt to it quickly?

Mmm… I didn’t play seriously until probably years later, when I made the decision that this was what I was going to do.

By the time you got out of high school, you guys had already been playing together a while.

Oh yeah. By the time I got out of high school, I graduated in ’69 and we recorded in ’70. So yeah, the decision was made by then.

How many Tower albums were you on before you left the band?

From the beginning until Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now [eight albums]. Then I got fired in ’77, and they rehired me in ’84.

In the interim had the band changed much?

Well, the way I understand it, I should be happy I wasn’t there during those years. They were pretty lean times for the band. A lot of changes went on. I wasn’t expecting to come back, so when I did it was like coming home, you know. It was all good. Once I settled in, it was fine.

Was David still the drummer?

I don’t think so. He was in and out so many times.

After you got assigned to play bass …

When I started to really establish myself as a bass player, I grew up with sounds. It was Motown, it was Philly, it was Chicago – it was sounds. Like James Brown. Whenever I heard something new, I’d try to get that kind of groove. As far as the players, I didn’t know who the players were ’til much, much later. There was Jamerson and Carol Kaye, but there are people I don’t know to this day. I keep hearing little tidbits about people who were around back then. Nathan Watts is a good friend of mine, and he’ll tell me about some guy – “So and so played on that.” “Really?” I’m still kind of flabbergasted by who did what and when. But the Chuck Raineys and Jamersons and the guys on the Philly stuff were influences.

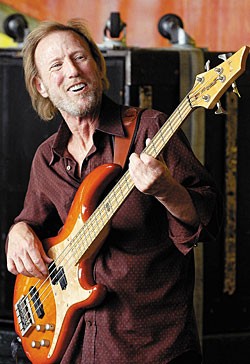

Prestia with Tower of Power at New Orleans Jazz Fest in early ’08. Photo: Clayton Call.

In terms of the parts you played and developing your styles, were you pretty much left to your own devices?

The band was pretty much free like that, yeah. And back then it was a lot easier to have a “band.” It’s harder to do that these days, I think, comparatively, especially as you get a little older and start having responsibilities. Which is fine, too. But we were doing original music early on, so we had a chance to create a style. Looking back, you don’t realize that’s what you’re doing – especially something like being a bass player; I was just a guy in the back. I’m not the songwriter or anything. But as years go on, people say, “Oh, man!” You just take it with a grain of salt. Then you wake up one day and look at your history and, “Yeah, I guess I do play differently than other guys.” But you – at least I – just don’t think about it. I play a piece of wood with some frickin’ metal. I play the way I feel. The tunes have certain outlines, for sure, but there’s a lot of freedom, and I certainly try to take advantage of it. It can cause you to mess up sometimes, but so what? You should go for it and have some fun.

Being able to create a style and be in an organization for so long gives the opportunity. Guys ask, “How did you do that?” Well, that’s how it happened. If I’d been bouncing around playing with many groups, I wouldn’t have had that opportunity. Maybe it would have happened, but it would have been different than it is now – let’s put it that way.

When you talk about it being easier to be in bands then, you also were in a certain time and place – the Bay Area.

That was the time for music, man – bar any place in the country. No question about it. The Fillmore, Bill Graham – forget about it. There was no place like that in the world.

A lot of rock history written by people who weren’t there typify the Fillmore and Avalon audiences as a bunch of stoned hippies who’d go for anything. But those audiences knew good from bad, because they were exposed to so much.

Oh, yeah. It’ll never be duplicated. It was incredible. I mean, superstar bands all together in one night – that was just a common thing. It wasn’t even like, “Well, if we could.” Bill was the only guy in the country who could pull it off. Fillmore East was a disaster, though (laughs)! It was just a crappy venue.

In terms of the “San Francisco sound,” the East Bay was different.

Well, we went out of our way to separate. It was important for us to separate from that whole San Francisco sound. Because we weren’t like that. It was real important for us to identify with the East Bay. That’s what we were.

Was it natural that the East Bay had more of a funky feel, or was it just a coincidence that you guys happened to be there and were a funky band?

Hell, I don’t know. The Whispers were around then, the Natural Four – there were singing groups, but they were soul.

Do you remember a group called the Spiders with a singer named Trudy Johnson?

Oh, man! That was our favorite group. Trudy Johnson was Terry Saunders’ old lady. That was the band. Even to this day, those were the guys.

They played high school dances and I.D.E.S. Hall, this little union hall.

That was the place! A big little barn.

When you started developing a style, unconsciously or not, was it natural that a certain technique developed, or was it something you studied?

Oh, no.

Is your right-hand picking two fingers or three?

Just two. It’s just the way I play. The best way I can describe what I do is, it’s just very percussive. That’s the way I play. I mean, I’ve tried to play lines [differently], and it just sounds weird.

Who are some of your favorite bass players?

The guys with James Brown, from Sly… Larry Graham. There was Duck Dunn, Chuck Rainey, Jamerson, Jerrold Jemmott. I wasn’t big into rock guys. Once I got into soul, that was it. That old soul stuff is where I come from. I don’t listen to music that often, but when I do that’s what I listen to.

All the influential R&B bass players who’ve been the building blocks for the ones who followed are very different, stylistically.

And all those guys are very well-educated, the way they came up. But yeah, there are a lot of styles. You don’t see it too much anymore. It’s pretty interesting to think about it.

The role of the bass player in this group…

It’s a job, man.

It’s maybe the only group where the horn players are more famous than…

That’s a matter of opinion…

I was going to say than the singers – because Tower has had a succession of lead singers.

Well, there was Blood, Sweat & Tears, Chicago.

But they weren’t funky like you guys.

Completely different. But they made the money (laughs)!

It’s a combination of everything. It works together. Inside the band, we tease each other, but the horn section and the rhythm section go together like a hand and glove – especially when [trumpeter] Greg Adams was arranging. He knew how to arrange the horns to get the maximum out of the section.

Are you cuing off anything specific?

Oh, sure. It could be a horn line; it could be a vocal; could be a setup on the drums. Any number of things could set it up – a change or a dynamic, whatever. But there’s always something you’ve got to cue off.

Tower’s first album was produced by David Rubinson.

Yeah, and then the second one was produced by Steve Cropper.

After that, the band produced its next several albums. Were those done by committee, or how did that work?

Everybody had input, but the bottom line goes back to Mimi. He would be the “executive producer,” no matter.

Why were there so many singers in this band?

Because we got tired of their asses!

Usually that would spell failure for a band because the audience identifies with the singer.

For whatever reason, they either wouldn’t work out, or they’d leave on their own. You know, singers in general are freaking head cases. A lot of them have “L.S.D.” – Lead Singer Disease, for anyone who doesn’t know. We had a lot of great ones, though.

Was Everybody On The Bus your first solo album?

My first and only – unless you’ve got some paper (laughs)!

After being a band member for so long, how did you decide what direction to take for a solo project?

I didn’t, really (laughs). It’s what was available at the time – tunes I had written. I’m not a real writer, so at that particular time of my life… staying up all night partying, we wrote a lot of tunes. And what came out came out. As far as a solo album, it was an opportunity offered, and it just worked out. I never really worked in that way, like, “Oh, I’ve got to do this.” It just kind of fell in my lap. But I’d love to do another one.

It’s mostly small-group configurations, and not a lot of horns. Did you purposely go a different direction than the bigger, horn-heavy Tower sound?

Yes, I did. I mean, what’s the point? If I’m going to do that, I might as well call it Tower Of Power II. It wouldn’t be the same type of tunes, but it would sound alike.

I did use some of the guys in the band, though. Jeff Tamelier was the [Tower] guitarist before Bruce came back, and I used Doc; they went together a lot.

You also play on Doc’s Strokeland Superband CDs.

Right. That’s not a “band” band. Mostly he would use our rhythm section, but the way we would do it is we’d go in, rehearse, and just knock it out the next day. Whereas with Tower it’s a lot more arranged. So it’s kind of unique. I kind of like it; it keeps it fresh, and gives you a chance to kind of go after it. I actually enjoyed it quite a lot. It puts a little pressure on you, and that’s always good, too.

What’s your amplification setup?

I had a deal with Eden, and I had a deal with SWR – so I’m using an SWR 1,000-watt head and a new Eden bottom with eight 12s.

What kind of strings do you like?

Dean Markley makes them – they have my name on them and everything. They’re NPS RoundCore – I think .045, .065, .085, 1.05. I’m involved with all the development of everything that I use, and once it’s done, why retain that stuff?

Is your bass custom-made?

It’s a Conklin [Groove Tools GTRP-4, co-designed by Prestia]. He’s out of Springfield, Missouri. It was supposed to be on the market, but the deal for distribution all kind of dissipated, so I don’t know if there are any others out there. I have a few. I like the way it feels; I like the balls, the tone. It’s right between a P and J. It’s just personal preference. I’m not into expensive; I’m into what feels good, sounds good – I’m happy. Like I said, it’s a piece of wood.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s January 2009 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

ROCCO PRESTIA & TOWER OF POWER