Photo: Rusty Russell

Brent Rowan is a 29-year veteran of the recording industry who has worked with legendary country artists including George Jones, Glen Campbell, Chet Atkins, and George Strait, as well as current country superstars like Tim McGraw, Kenny Chesney, and Brooks & Dunn. Pretty impressive, but what you would expect from a top session guitarist in Nashville. But also on his list of credits are names you might not expect, like Etta James, Amy Grant, Bob Seger, Roy Orbison, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Brian Wilson, and even Led Zeppelin frontman Robert Plant. With his reputation for playing the right part, with the right feel and tone, it’s no wonder he gets so many diverse calls.

Born in Texas, Rowan grew up in the suburbs of Houston. Raised in a strict Pentecostal household, his upbringing meant he was not allowed to listen to the rock music that inspired other musicians of his generation. But there were advantages to growing up in the Assemblies of God Church, where electric guitars and drums were commonplace. And while his pre-pubescent counterparts were banging away in their garages, Rowan was plugging in and rocking out every Sunday night. He not only learned how to play in the context of a group, but about how music can affect people.

At 17, Rowan graduated from high school and moved to the outskirts of Chattanooga, Tennessee, to play in a touring gospel group. There, he got a taste of the road and the studio. After watching session guys play all day and sleep in their own beds (instead of a tour bus), he moved to Nashville.

Through fortuitous encounters, he soon scored a gig with country artist John Conlee, and in 1980 played guitar on the #1 hit “Friday Night Blues.” Soon after, he was turning Nashville on its ear. While house drums and amps were then the mainstay, Rowan bucked the system by insisting on bringing his own amp. When this became common practice by the mid ’80s, he introduced Nashville producers to the stereo “rack” sound that was all the rage in Los Angeles studios.

Rowan spent the ’80s recording with the top country acts including Alabama, Hank Williams Jr., Reba McEntire, and Keith Whitley. His dominance as a session guitarist was exemplified by playing on six of the top eight country singles on the July ’86 charts.

The ’90s continued to find him playing with top artists such as Clint Black, John Michael Montgomery, Little Texas, and Tanya Tucker. A personal highlight of the decade was participating in the acclaimed Nashville Network show “The American Music Shop.” As part of an all-star band, he backed artists ranging from Gatemouth Brown and Bruce Hornsby to Albert Lee and Larry Carlton.

In 2000, Rowan released the critically acclaimed acoustic instrumental album Bare Essentials. By that time, he was not only a player of renown, but an artist in his own right. And soon, the pieces came together to add yet another title to his resumé – record producer. After eschewing the role for years, Rowan made the plunge with Joe Nichols’ 2002 album, Man With A Memory, which spawned three Grammy nominations and two #1 singles. With Nichols’ success, Rowan became not only an in-demand session guitarist, but producer. And today, in his third decade as session guitarist, his playing is still heard at the top of the charts.

Rowan recently spoke to VG about growing up in Texas, playing in the studio, the keys to his longevity, and his impressive collection of vintage instruments.

How did you start playing the guitar?

My parents gave me an acoustic when I was 9. I’d already been playing piano and harmonica. The day the piano was delivered, I picked out the melody to “Jesus Loves Me” in the first couple of minutes. When I was 7, my grandmother gave all of us kids harmonicas; by the end of the day, most had lost theirs, but I was playing songs. When I got the acoustic, my parents said if I learned to play it, they would get me an electric guitar for Christmas. By September, I’d decided that was what I wanted, and learned to play it well enough that they bought me one. I was raised with a very traditional Pentecostal background, and those church bands in South Texas were rockin’. You really learned the value of connecting with people on an emotional level through music. The music was talking to people’s hearts; it wasn’t trying to wow them. I tell people it’s the closest thing I could have had to the black church experience.

I had very different influences from my friends who were playing the guitar. I wasn’t allowed to listen to people like Clapton and Hendrix. And I wouldn’t change a thing. It meant I worked with a whole different set of influences. You find what you can and work with it. I play different from a lot of other players because the power of the guitar came second to the power of music. I wasn’t listening to guitar players learning their licks. I was ingrained with “you can make people happy with this” or you can touch people on a deep emotional level that they might not know why they’re being touched. I started playing at the same age most people did, but came from a different place. I didn’t have a guitar hero, but I played music to help people relate to my Hero.

If you weren’t listening to other guitar players, how were you learning how to play?

I had one or two Chet Atkins records, but his style didn’t really fit into the music I was playing. I was learning from other guitar players in the church orchestra. I had no obvious heroes.

Having not listened to other players, who would you have compared yourself to among contemporaries?

Probably Clapton. When I was playing on sessions, people would comment on a riff being like something he would’ve played. I think it goes back to people like Muddy Waters, this emotional spiritualness where the guitar is just a vehicle to transmit emotion. I think that’s where the commonality is. I remember making potato art in grade school; everyone did moons and stars, but I made a guitar. The teacher asked about my choice, and I said, “That’s what I’m going to do when I grow up.” There was always a voice inside, guiding me. The thought that any of this would not work out never occurred to me. I look back now and think you would have to be crazy to move here and expect to make it. I didn’t know that Nashville didn’t need another guitar player! Sometimes ignorance can be a good thing. I felt like I was put on this planet to communicate to people through music. The guitar just happens to be the tool I use.

What was your first guitar?

It was a Kingston. My first electric was a Spacemaster with an Alamo amp. I still have both. They were both made in the U.S., which was a big deal to my parents. Most of the Montgomery Ward stuff was being made in Japan by then. They bought them at H&H Music, in Houston. I’ll always remember getting them and learning my first song – “I’ll Have A Blue Christmas Without You,” by Ernest Tubb. My parents had the 45 and I would play along, then go and play with the church orchestra. That Kingston acoustic had the strings so far off the neck it’s a miracle I learned to play.

When did you start listening to non-church music?

At 17, I graduated high school and moved to a suburb of Chattanooga to go on the road with a gospel group. I was around other musicians whom did not share my background. I’d never been to a movie – I was 20 years old the first time I saw a movie. I was quite sheltered. I was able to listen to some country music growing up, though. I was familiar with Charlie Pride and Johnny Cash. I loved those records; the guitar parts really took you on a journey. There wasn’t a lot of virtuoso flash, but it created a mood. The first rock album I bought was the Eagles’ Greatest Hits, and Linda Ronstadt’s Hasten Down The Wind. Again, I was attracted to emotional content – I loved those players; Bernie Leadon, Glenn, Waddy Wachtel, and Andrew Gold. I really liked Andrew’s playing because it was very orchestrated and arranged. Like the solo on “When Will I Be Loved”; to my taste it doesn’t get better than that. I also remember hearing stuff like Olivia Newton John – John Farrar played, produced, and wrote much of her material. He was another influence.

Tom Anderson-built guitar used a lot on Julie Roberts’ ’04 self-titled debut album, which Rowan produced. Photos: Rusty Russell

1960 Gibson ES-335. Heard on the Mark Chesnutt hit “Too Cold At Home.”

A PRS Custom 22 used heavily on Montgomery Gentry Some People Change album.

What was your next guitar after the Spacemaster?

My next guitar was a 1971 Gibson ES-335 in walnut that my mom and dad bought me, along with a Fender Twin Reverb. That shows you the wisdom of parents, because I wanted a Jaguar with a Kustom amp. He insisted on getting a Gibson guitar and a Fender amp. I played that Spacemaster for five or six years, though, and was proud to have it. I didn’t know you couldn’t play music on it. The Spacemaster had a 3/4-size neck. I didn’t know my hands might outgrow it, or even that you weren’t supposed to change strings until one breaks.

How long did you play with the gospel group?

About three years, then I moved to Nashville. When I moved there, I knew two people – the guy who I shared a house with, and Dave Huntsinger, a keyboardist with the gospel group The Rambos. The day after I got to Nashville, Dave called me to play with the Rambos. I did that for a while, and that’s where I was around non-church guys and got exposed to groups like The Eagles. These are the same guys that took me to my first movie, Dirty Harry. I couldn’t believe how big the screen was, and I was freaked out by the blood and such.

What was your first pedal?

It was an Electro-Harmonix volume booster, then an E-H Small Stone phazer and a script-logo Dyna Comp. At this point, I became aware of guitar magazines and started reading about other players, and what they were using. I loved reading about guys like Larry Carlton and Tommy Tedesco. I just tried to expand my horizons. Also, whenever I would find a guitar player I liked, I’d find out their influences and listen to them, try to chase it back. I always loved the guys who played from the heart even if they might not have had the most finesse.

How did you start doing sessions?

When I lived in Chattanooga, we’d go to Nashville to make albums. I didn’t get to play on the records, but the bandleader would hire me to work on other projects he was producing. He started using me on acoustic guitar on the sessions. Through this, I saw that the session guys were playing 12 hours a day and sleeping in their own beds every night. I never really loved live playing; it seemed like 23 hours of waiting to play one hour. We had to set up the merchandise table, set up the P.A., all to play one hour. On the session, I saw all these guys playing multiple sessions in the day, then sleeping in the same bed every night. I decided that’s what I wanted to do.

After a hiatus, the Rambos decided to tour again, but I opted against it. I had already figured out how to make my living conditions work and was ready to starve to do it.

What year was that?

1978 or ’79. So I stayed in town. One of the smartest things I did was to go around with my demo tape, and offer to play. I’d tell people I knew they probably had someone that they normally used, but if they were not available, I’d love a shot, and offer to play for free. I told them to only pay me if they liked what I did. I think people were impressed with that. They either thought I knew what I was doing or was really crazy. People were usually willing to bet on me. Looking back, it looks really smart. That’s advice I would give to anyone. Find what you love, and do it for free until someone is willing to pay you. No one ever asked me to play for free, but I got calls because I was willing to take all the risk.

One of the first guys to use me was Terry Choate, at Tree Publishing, and an engineer named Les Ladd. Bud Logan wanted to bring in new blood and Les recommended me. So I got to play on John Conlee’s “Friday Night Blues,” doing a three-part harmony solo. Bud loved it, and I ended up playing on every Conlee record Bud produced. That was my entrance. People heard what I did, said, “That’s different,” and I got more calls. Many times I’d play on demos at Tree and the producer would call. More than once, other players would be asked to mimic what I played on the demo. Other times the player wouldn’t be able to do it, and I would be called in to re-create the part. It was not about the part being complicated, it was just a feel thing.

And how do you learn to be a true session player?

My goal, if they were to pull up stuff that I played on 100 years from now, is that you’d hear my guitar part and have a sense of what the lyric is. I want to communicate the same emotion the singer does. Rule number one is “It’s not about you. You are part of a team.” That’s the biggest thing. If I help other people reach their dreams, I usually help myself reach mine.

Who were the top session guys when you came to town?

Reggie Young was doing a lot of the work, and Pete Bordonalli was doing a lot of the rock-type stuff.

What equipment were you using on those early sessions?

The 335, a black-box Echoplex, MXR Distortion+, Dyna Comp, and a volume pedal. I’d read that Larry Carlton was using a lot of that stuff. I also had a Electro-Harmonix Small Stone flanger and an Electric Mistress. I started learning about racks, and was one of the first guys to go that route. I was one of the guys to help ruin the sound (laughs)!

Were you carrying around the Twin?

No, I read about Paul Rivera and had him mod a Deluxe like he was doing at that time for the L.A. session cats. I had that and a brown-tolex Princeton. I used to carry all my stuff around in a Ford Pinto. I think “Friday Night Blues” was done with one of those amps, the 335, and a Dyna Comp.

When did you help bring the rack era to Nashville?

I always wanted to be different. That can lead to success, or it can lead to tragedy. In the early 1980s, everyone was using the same house drum kits and amps at studios. I began to bring my own amp, just to provide a different sound than what everyone else was using. The rack thing started for me with mounting an Echoplex, and some pedals in a rack all connected to a patch bay. That way, I could plug into just what I needed for each song, and keep a more pure sound. I also put in a loop for my volume pedal, so it would always be before my echo unit. After that, I got a Valley People compressor/EQ and noise gate, along with a Lexicon reverb unit, and began to plug in direct. This was in an era when producers in Nashville were trying to get as pristine a sound as possible. So we began to plug in direct, and pretty much quit using amps for a while. A good example of this sound would be the T. Graham Brown album Don’t Go To Strangers. Other players started going direct after that also, so I changed again. I found out about Bob Bradshaw, who made the first system where you could hit one button and change multiple parameters.

How did you get the idea for that first rack with the patch bay?

I think part of it was I was single at the time, and just lived and breathed it, and was always looking for a better way of doing things. It made sense to me to just use effects I needed, because that’s the way studios worked. In a studio, they don’t have a mic plugged into every compressor – they patch it only through the unit that they are going to use. I was working three or four sessions per day and didn’t have the time to set up a bunch of pedals, then pack up for the next session. I was just thinking of a better way to have many choices without degrading my tone.

Tell us about the first Bradshaw rack you had him build.

It was funny; I was using a lot of the units that he was incorporating into his racks. He asked if I’d heard about some of the racks he put together for the L.A. guys. He was surprised that I was already using most of the stuff he recommended. One unit was the Dyno-My-Piano Tri-Stereo Chorus. I bought one when I heard one used on electric piano, and found out he was using them on guitar, as I was. I had him make a drawer for some pedals, because I still wanted to be able to use a Dyna-Comp on the front end if I wanted to. He said he wasn’t doing that at the time, and tried to get me to drop the pedals for rack compressors and stuff. But I insisted, and Bob ended up making that an option on his racks. I loved having all the options.

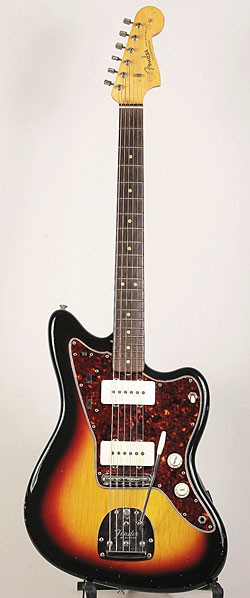

1963 Fender Jazzmaster Rowan uses for “in-between” Fender and Gretsch sounds. Photos: Rusty Russell

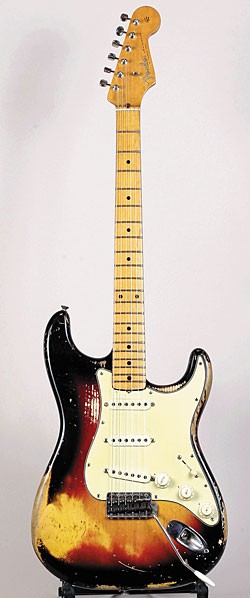

1960 Fender Stratocaster with a ’58 neck used on Bob Seger’s Face the Promise.

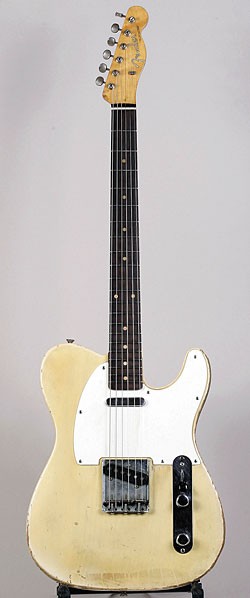

1952 Fender Telecaster heard on Kathy Mattea’s “Walk The Way The Wind Blows” and Rowan’s early John Conlee work.

What was next in the evolution of your guitar tones?

Everyone started to use racks, and digital recording became the new thing. That early version of Pro-Tools was very brittle-sounding, so I began to carry my own mic preamps. The rooms I was working had SSL boards, and I detested the sound of them on guitar, so I’d bring a set of Neve 1272s. I would also bring a matched pair of Shure SM-57s. Then I could just hand the engineer a pair of XLR cables and sound more like I wanted to. That helped me differentiate myself from the other players in town. Another thing I did at the time was to give them two amp signals, and two direct signals. That would just give the producer more options.

On the session today [for Josh Turner], you had two setups…

I have both an amp and pedal rig, and a stereo rack setup. Some producers still like that rack/stereo spread sound, and there are some songs that really do call for it. Most producers have weaned themselves, but a few still insist on it. For the most part now, I’ve gone back to pedals. I only plug into the pedals that I am using for that song because the sampling rate has gone up so much that it makes a big difference. To my ears, there is a big difference between going through a pedal in bypass mode and taking it out of the chain altogether. It also increases the lag time between hitting the string and feeling it. I no longer use a pedalboard. I have a case full of pedals, and pull out just what I need.

Tell us about some of your amps.

I’ve got a Marshall JTM 45 and a plexi JMP 50, a Dr. Z Carmen Ghia, a very early Bogner head, an Egnater, a Bogner Fish preamp, and a Marshall 100-watt I use with a 4×12 cab for more rockin’ stuff. Some of the first stuff I did with my first true stereo Bradshaw rack was Tim McGraw’s “Don’t Take The Girl.” That was one of the tracks that also had some direct sound mixed in. You don’t get that much chime on top of the fundamental without going direct.

Your amps include a mid-’60s Vox AC30…

I bought it from Billy Sanford, who used it while he was playing with Roy Orbison in the ’60s. I was working with Billy, and I asked him if he had any stuff he was wanting to get rid of. He mentioned an old Vox. When he pulled the amp out, he found a pair of drumsticks that had written on them “To Billy, From Ringo” on them. When Billy was playing with Roy in England, the Beatles opened shows for them.

What’s in your rack, effects-wise?

A Dytronics Dyno-My-Piano chorus, two Lexicon PCM 42s, PCM 70 for circular delays, TC Electronic 1210 Spatial Expander, Harmonizer H-2000, DBX-160, and a Hush unit. I keep all this stuff because I know someone will ask for it at some point. It’s funny, there was a time when you wouldn’t have been caught dead using a spring reverb, but things keep coming back around.

What kind of speaker cabs do you use with the rack setup?

A pair of Pacific Woodworks 1×12 cabs with EVM 12L speakers.

What about the 4×12 cabs?

I have two stocked with Celestion Vintage 30s and one that might have those old 18-watt speakers. I don’t know. All I do know is that it sounds good.

What amp are you using with the mono pedal/amp rig?

It’s the THD Flexi-50, which I really love. And I either use a THD 2×12 cabinet with two kinds of speakers, or a 4×12 with it. I like the Keeley compressor, modded Blues Driver, and Tube Screamer. I have a bunch of Menatone effects. I almost always use a Fulltone Tube Tape Echo, and I also like his OCD pedal. The Peterson Strobo-Tuner, an MXR Dyna-Comp, and almost every Boss pedal made. I use the Tremolo and the graphic EQ pedals a lot.

What do you use the Boss EQ pedal for?

If there’s a frequency that’s being over-treaded, I’ll cut it or boost frequencies that are not being covered as well. I also try to never compete with the vocal, so I’ll use the pedal accordingly.

What are some other often-used tools?

There’s a volume pedal. I got from Al Perkins, by Anapeg. It’s powered with a preamp and sucks the tone the least of all I have heard. I put all my pedals in front of the volume pedal, except for delay. That way I can control residual noise levels.

What other amps do you use?

I have some Victoria amps and a silverface Fender Deluxe that Kye Kennedy blackfaced for me. I love the sound of it. I try to create a sound for an artist, and then not use that same sound for other artists. This is the third Josh Turner record I’ve worked on, so I know where his voice sits, what has worked in the past, and the size of the band. Sometimes I use an old Bassman head with him.

What’s in your “Josh Turner rig?”

Some of the songs are heavy on the baritone, with low-strung guitars augmenting his voice, but never getting down to where he is, range-wise. Then there’s this crazy, whacked-out Tele guy that is part of his band, in my mind. This guy is part Brad Paisley and part James Burton. He appears on each album a couple times. With those parts, I try to walk a fine line playing parts that will make people think “Is he kidding, or is he not.” Frank Rogers, Josh’s producer, loves that, and he produces Brad also, so he borderlines on whether or not they’re kidding. Pure tones for Josh, not a lot of processing. On some songs I did use an E-H Holy Grail because I think verb before the mic can sound so heavenly.

In the studio you have all these toys to choose from, but if you were to play a concert with Josh and were limited in what you could carry, what would you take?

Guitar-wise I think I would take my ’60 slab-board Fender Telecaster, a Jerry Jones baritone, and a Jones six-string bass. Amp-wise, I’d use my Deluxe and take a volume pedal, delay, compressor, Boss EQ, Keeley Blues Driver or Tube Screamer, and a Tremolo. With those, I could cover all the tones on his records. The guy on the road can’t afford to change stuff around every single song like I can.

What’s the story with the slab-board Tele.

Steve Henning found it for me. He and his dad have Heart of Texas Music in Austin. I have a couple of older Teles, but was looking for a nice rosewood-board. This one came through, and they sent it to me. Michael Stevens flattened the radius of the fingerboard and put slightly bigger frets in it – made it a much better player. So many early-’60s Teles are hard to bend on because of the overly curved fingerboard.

What are some notable songs you used it on?

Joe Nichols’ “Brokenheartsville” and all the Tele stuff with Mark Chesnutt like “Going Through The Big D,” and “Bubba Shot The Jukebox.” I also used it for all the Tele stuff on Josh Turner’s records.

What’s it strung with?

D’Addario .010-.046.

Do you have a brand preference?

No. Sometimes a GHS Nickel Boomer will sound better on a guitar than another brand will, but a D’Addario or Ernie Ball might sound better on another guitar. I also use different gauges to make me play different.

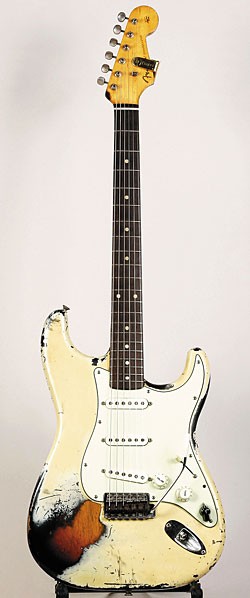

What about the Olympic White 1960 Strat?

Somebody called me, wanting to sell a guitar. I didn’t need it at the time, but boy am I glad I bought it. It has a wonderful, Stevie-Ray-type of throaty tone. I love it. It has an original finish with a three-color sunburst underneath.

And some tracks you used it on?

On all of Blake Shelton’s Pure BS, which I produced and played on. Also, some Montgomery Gentry stuff I’ve played on.

And your ’58 Strat…

It’s a ’58 neck with a ’60 body. One of the later Burrito Brothers sold that to me more than 15 years ago. I used it a lot on Bob Seger’s Face the Promise album.

1960 Fender Stratocaster in original Olympic White with three-color sunburst underneath. “It has a wonderful, Stevie-Ray-type of throaty tone,” says Rowan. “I love it.” Photos: Rusty Russell.

1960 Fender Telecaster with flattened and re-fretted fingerboard.

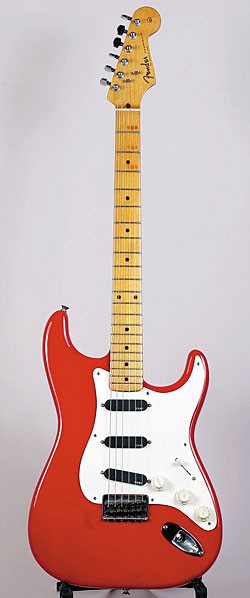

1956 Fender Stratocaster refinished using an original can of Fiesta Red. Bought from Americana/progressive country songwriter Willis Alan Ramsey.

Double-bender instrument made by Nashville builder Joe Glaser. Heard on Lorrie Morgan’s “Sure Is Monday,” and “Daddy Never Was The Cadillac Kind,” by Confederate Railroad.

How would you compare the ’58 with the ’60?

The ’60 is throatier, while the maple neck has more “ding” to it. I think of maple as having “ding,” and rosewood as having “dong” tonal qualities.

You’ve also got a cool Fiesta Red Strat with EMG pickups.

It’s a ’56 that Joe Glaser refinished with what was supposed to be an original can of Fiesta Red he found. I bought it from songwriter Willis Alan Ramsey about 20 years ago. I have the original pickups set aside.

Why the EMGs?

I have two vintage Strats with noisy pickups, so it’s nice to have one that’s quiet. Also, I heard an old Ronnie Milsap song that I had played a Strat with EMGs, and liked the sound. We re-cut Mark Knopfler’s “Prairie Wedding” with Kenny Rogers, and I used that guitar. It really nailed the sound. The EMGs have a little more sustain. I also used that guitar on Tim McGraw’s “Down On The Farm.”

What about the Jazzmaster?

It’s a ’63. I picked it up at a music store in Colorado. I love the Gretsch sound, but I wanted something in-between Fender sound and Gretsch. That guitar does it. I put big flatwounds on it.

Tell us about the white Tom Anderson…

That’s a great go-to instrument and amazing all-around guitar. I used it a lot on the Julie Roberts album I produced.

The ’52 Telecaster.

I’ve had that the longest. I used it on Kathy Mattea’s “Walk The Way The Wind Blows” and some of the early John Conlee albums.

What about the PRS with the black middle pickup?

He just made that for me. I’ve known Paul for about 20 years; he, Tom Anderson, and James Tyler all make fantastic guitars. Paul sent it to me, and it sounds older, and more musical than most new guitars. On youtube.com, you can check out that guitar on a PRS demonstration I did with Gary Grainger. Most new guitars just sound new. This one sounds like an old guitar. I used it a bunch on the newest Montgomery Gentry album.

The Jerry Jones Sitar.

I use that once every three or four years. Sometimes I double parts with it to add a clavanova effect. I used it on the recent Joe Nichols single “It Ain’t No Crime.”

The Glaser Bender guitar.

It was one of the first double-bender instruments that he made. I loved the sound of the Eagles “Peaceful Easy Feeling.” I used it on Lorrie Morgan’s “Sure Is Monday,” and “Daddy Never Was The Cadillac Kind,” by Confederate Railroad.

What about this incredible Cherry dot-neck Gibson ES-335?

It’s a 1960 that I bought that from Corner Music years ago. I used that on “Too Cold At Home,” by Mark Chesnutt.

The Tyler.

That’s one that James made for himself. I played it, he let me borrow it, and I sent him a check instead of the guitar! I used it on the long outro on Mark Chesnutt’s “I’ll Think Of Something.” It was also on John Michael Montgomery’s “I Love The Way You Love Me,” and Joe Nichols’ “Man With A Memory.”

How essential is having a collection of guitars to session playing?

It’s not essential, but different guitars and amps make me play differently. It also helps me keep from having a “signature sound.”

In the early 1990s you performed on the “American Music Shop” on TNN. How did that come about?

Mark O’Connor called and asked if I would be in the band. We had Jerry Douglas, Harry Stinson, Matt Rollings, and Glenn Worf. It was a great band, and everyone from Bruce Hornsby to Gatemouth Brown to Tony Rice played on the show. I got to play Tony Rice’s guitar. One of the funniest things was having Larry Carlton on. We wanted to play songs like “Room 335,” but he wanted to do things like “Steel Guitar Rag.” Vince Gill was also part of the band, and we were both very much in awe of Larry. That show was a lot of fun. I hope someday it’ll be rebroadcast.

How did you get into producing records?

I never set out to do it. I’d thought about it, but decided that if I was going to do it, it was going to have to be great, because I can do good all day. Production takes a whole lot of time. My cartage guy kept giving me a tape of Joe Nichols. I met him, and he was five days from moving back to Arkansas. The first song we did was “The Impossible,” and it went to #1 and sold a million units. The next act I produced was Julie Roberts, and her album did really well, also. I look for artists who talk to my heart.

Do you play all the guitar parts on the albums you produce?

Pretty much, except I use Bryan Sutton or Mac McAnally on acoustic. On Blake Shelton’s record, I made Blake play acoustic, which really helped make it sound even more uniquely like his record. The latest single, “Home” is a huge hit, and it was really gratifying to Blake that he had such a part not only vocally, but musically.

Who do you most get into listening to right now?

Tom Petty and Mike Campbell. I have Wildflowers in one car and Highway Companion in the other. Those albums have all the tone, taste, and soul that you would ever need. I still love Andrew Gold’s playing. I’ll buy whatever Mark Knopfler does. And somebody who really surprises me is John Mayer. I love guys who play from the heart. Who cares how fast you can play? Does it come from the heart? That’s all that matters.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s December 2008 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

Brent Rowan & Gary Grainger in the PRS booth