Judging by the melee of favorable product reviews, Reverend guitars go beyond colors and chrome to inspire comments like, “…has the feel and finesse of a $2,000 guitar…instant blues machine…superior resonance and sustain…warm and midrangy with the perfect amount of upper-end shimmer and jangly sparkle…”

Whence cometh these righteous instruments that spawn such praise? Would you believe Eastpointe, Michigan?

Around the back of a small commercial building on Gratiot Avenue you’ll find a white garage door punctuated with a 4″ X 8″ retro-look sticker that reads “Reverend Musical Instruments.” Knock on that door and you’ll meet Joe Naylor, the man behind Reverend guitars.

You may have heard the name Naylor before, attached to a line of acclaimed speakers and hand-built amplifiers. In 1996 Joe sold his interest in Naylor Engineering, the speaker and amplifier company, to found Reverend Musical Instruments. These days behind that door you’ll find Joe, his wife Kristen, right-hand man Kraig Sagan, and three other employees.

Reverend Musical Instruments is a two-room operation that each month produces about 65 guitars and basses bearing names like Slingshot, Avenger, Spy, and Rumblefish. The larger of the two rooms houses raw materials, tools, jigs, and more. In this room the guitars take shape as a white mahogany center block, a steel bar, a molded rim, and a brightly colored phenolic laminate top and back are joined together. The smaller room houses the office, along with the electronics and the final assembly/setup operations.

Vintage Guitar: Describe your journey from guitar player to guitar designer/manufacturer.

Joe Naylor: I was into guitar players before I played guitar. Pete Townsend was my idol, along with Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck – the old-school guys. I have three brothers who play guitar, so there was always a guitar around the house. My older brother would lock us in his room and make us listen to him playing along with Hendrix and Cream records. If we tried to get up, he would push us back onto the couch.

I started playing in 1980, and I knew almost immediately that I wanted to work on guitars. I began reading everything possible, bothering repairmen, things like that. I was guitar bloodthirsty.

I learned a lot of repair on my own. I got an old Guild from my brother. I had it with me at Western [Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Michigan], and I ripped it apart and rebuilt it. Then I decided to refret it, so I yanked all the frets out and brought the guitar to a repairman in Kalamazoo named Pete Moreno. He’s one of the best in the world. Since I couldn’t afford to pay him to do the refret, he gave me some fret wire and carved me a little neck-holding block, and he pounded a couple of frets in to show me how to do it. That was my first foray into repair. Then I started repairing guitars for other students.

After I graduated, I decided I wanted to repair and maybe build guitars for a living, and that it was time to get serious. So I went to Roberto-Venn School of Luthiery, in Phoenix. I remember getting off the plane and driving to the school – which looked like nothing more than a metal shack sitting on a big lot in the middle of the desert – my first thought was, “This is nuts. What a waste!”

Then the people took me inside and showed me two or three guitars that the instructors, John Reuther and James Weisner, had built. They were incredible, so I figured I’d better stick around. The course was three months long, but I stayed an extra two months and learned semi-hollow construction from James.

Have semi-hollows always been a focus?

Yes. Early on I was attracted to them because I liked a lot of the players: Alvin Lee, Pete Townsend, Chuck Berry, Billy Zoom, Malcolm Young. One of the first guitars I owned was a semi-hollow Silvertone, an amp-in-case model with a single lipstick in the neck position. It sounded incredible. When I realized that such a great-sounding guitar was made with masonite, of all things, I started experimenting with alternative materials – acrylic, aluminum, foam, different types of laminates, phenolics, plastics. I’ve probably built a guitar out of every conceivable material.

Did you use wood for the frame on your first guitars?

Yes, the early ones were usually wood frames with wood center blocks, similar to the Silvertone. I did one that had a foam center block – that was interesting – and an aluminum top and back. I probably built something like 30 or 40 bodies on the way to the current guitar. I would build a body and, if I didn’t like it, I’d run it through the band saw and throw it out. There aren’t too many of those first guitars around.

So when they open the Reverend Guitar Museum 30 years from now, they’re not going to have a collection of prototypes, just production models.

Actually I sold some guitars under the J.F. Naylor name. I probably built and sold 10 or so.

Were those unusual designs?

They were mostly masonite tops and backs, though on some of the later ones I started to use the phenolic. One of those masonite guitars is pictured in the 1987 Guitar World Buyer’s Guide.

What came next?

In 1992, my wife and I moved to Detroit and I opened a store specializing in sales and repair of used guitars and amplifiers. That was a laboratory for me, where I learned a lot about vintage guitars and what makes them tick. I would inspect and play every single piece of equipment that came in – whether it was the cheapest Hondo or a nice vintage piece.

We started Reverend in 1996. That’s when I came up with the injection molding process for the body rim and finalized the structural design of the body, which is patent-pending. We call it the high-resonance body.

You said you were always attracted to the semi-hollow sound. What in particular about that sound attracted you?

Initially, I was very attracted to the feedback aspect. I love feedback – Hendrix, Santana, and of course the Nuge in the early days.

One might get the impression you are aiming for something beyond the semi-hollow sound of the Silvertone and the 335-type guitars.

I’m trying to make a semi-hollow guitar that also appeals to a solidbody player. A Reverend has more attack and sustain than a Silvertone or a 335 because of the metal block. And the feedback is more controllable – all without sacrificing the resonance of a semi-hollow design.

What sound are you aiming for with these guitars? With the pickup configurations, each model is going to sound different, but is there some overall sound you’re after?

There is an overall sound you hear no matter what pickup you put in a Reverend guitar. I’m going for a resonant sound that’s very lively, very responsive to how you pick, a sound rich in harmonic content, with a wide frequency range – lots of high-end, lots of low-end – the sound you hear not only in a good semi-hollow, but also in a good, light solidbody. It’s an overall liveliness I’m looking for, and the Reverend body – compared to solidbodies, where some are good and some are duds – is a design that guarantees every guitar will be resonant. I was going for consistency.

Body resonance doesn’t depend on this big chunk of wood, which might be alive with tone, or might be dead.

Right. I tell people that a lot of my body is air, and air is fairly consistent worldwide.

How did you come up with the body shape? Was it an epiphany or a long struggle?

It was a combination of influences: Fender, Rickenbacker, Art Deco. I combined features from some of my favorite guitars of the ’50s and ’60s – Jaguars, Jazzmasters, Supros, Nationals – and put it all together into one. I was also influenced by what Paul Chandler started doing 10 years ago, combining vintage aesthetics with good, workable components.

And then you have the headstock, which is not Stratocaster and not Telecaster; it’s unique.

I wanted it to have an identity, but I also wanted it to be somewhat familiar. Guitar players are fairly conservative and if something is too far out, they won’t be attracted to it. I wanted it to be familiar, but I didn’t want it to be an overt copy of something.

What makes a Reverend guitar a player’s dream?

It has a vintage vibe and feel and a somewhat vintage tone, but not a vintage price tag. It also has modern reliability and playability. I guess those factors would make it a dream guitar for a lot of people. In fact, most of the people who buy my guitars either own or have owned vintage guitars.

And for many, there’s something about the way that neck fits into the hand…

That’s the vintage influence. The neck is patterned after an early-’60s Strat, but with a flatter radius (15″) and bigger frets, which is a common mod to older Strats. I guess that’s my crowd: a vintage crowd, a lot of blues and blues-rock players. Although a lot of younger players are picking up on it now.

Did you ever experiment with a string-through bridge?

By the time this goes to print Reverend guitars will have a string-through bridge. Our main motivation is to continually improve the product. We want to give our customers the best possible product, and if we can improve something, we’re going to do it. That’s our philosophy. I believe in continually evolving.

How did you decide on the name?

I was actively searching for a name, an appropriate name for a retro-type product. I was in a bookstore and I saw Blues Review magazine. I grabbed it, thinking, “There has to be a name in here.” So I started thumbing through it and the word “Reverend” came up two or three times. There was something on Rev. Gary Davis. As soon as I saw it, I knew that was it – Reverend!

It’s an effective marketing ploy with a few people. All the electric guitar-playing clergy I know play Reverend guitars.

Funny you should mention that. I’m building a roster of contemporary Christian rock bands. The bass player in Jars of Clay is touring with a Reverend. I get a lot of calls from contemporary Christian bands, and clergy. There’s a minister in South Bend, Indiana, playing one.

Is it the name that attracts these people?

I’m sure they like the guitar in the first place. But the name is the icing on the cake. Maybe it just says something to them.

That would really depend on the style of minister – the hellfire and brimstone types might really go for the Avenger. Which brings up another question – where do the model names come from?

Kraig and I make them up. Initially, we were going to go with all religious names like the Minister, the Bishop, the Friar, the Hellfire. But I didn’t want to get locked into that. I thought, “What happens when we run out of names?” So we decided just to pick names we like.

Who would you like to see playing a Reverend guitar?

I think Jimmy Page and Ronnie Earl would like my guitars. Billy Gibbons, too. It’s got his name on it – the Reverend Billy Gibbons.

How about the Rev. Horton Heat?

That would be cool. I’ve heard he really smokes.

We do have an active endorsement program. We recently added Rick Vito. He’s using a Spy on tour with Bonnie Raitt.

What’s next?

The Rumblefish bass is taking off really well, so we’re working on a five-string. I’m also working on a line of Reverend pickups that will probably be out this year. I’m considering doing speakers again, and maybe a small amplifier, all under the Reverend name. And maybe some larger-bodied, single-cutaway guitars and some higher-end custom models.

With birdseye phenolic?

Actually, I was thinking about that…

Contact Reverend Musical Instruments at 23109 Gratiot Ave., Rm. #2, Eastpointe, Michigan 48021, phone (810) 775-1025, fax (810) 775-2991, e-mail Reverendmu~aol.com, web site www.reverendmusical.com. Dealers inquiries can be directed to Rick Carlson, phone (530) 582-8889.

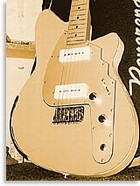

P-90 equipped Slingshot guitar with two-tone case. Photo courtesy of Joe Naylor/Reverend.

May ’99 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.