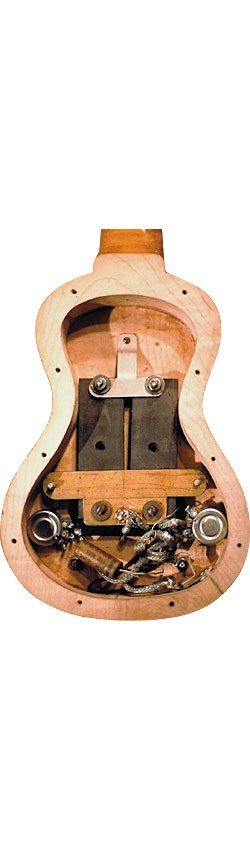

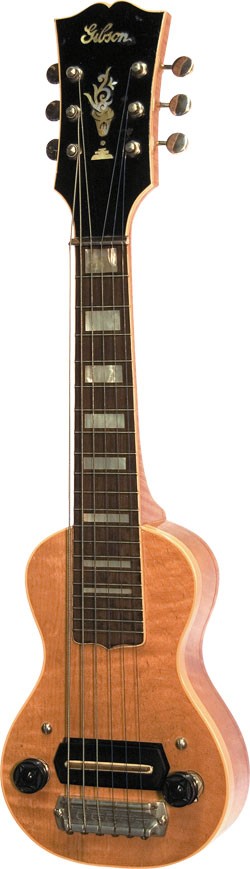

Alvino Rey’s 1936 Gibson mini guitar.

From its beginnings, Gibson has built custom orders and unique instruments for specific artists, sometimes by request, other times to lure a potential endorser. Manufacturers have always known that a popular player seen in public or shown holding an instrument in print (or on TV) can be key to the instrument’s commercial success. In 1936, an offhand remark by the most popular electric guitar player of the era prompted Gibson to woo that artist with two of the most unusual instruments ever to exit the Parsons Street factory in Kalamazoo.

Alvino Rey, who at age 24 was already a six-year veteran of the professional music circuit, made heavy use of the first modern electric guitar launched in September, 1932, by Ro-Pat-In. Though he doesn’t recall whether a salesman brought it to him or he bought it at a store, it was in his possession by the end of October that year. Even before that, Rey was acquainted with the potential of “electrified” instruments, having played an electrified banjo in 1929 with Phil Spitalney’s orchestra in New York.

Based in San Francisco by ’32, he was putting his Ro-Pat-In “Fry Pan” to good use, thrilling live audiences with music beyond the standard Hawaiian style of the period; as innovative as his instrument, he played melodies that blended more jazz-like phrasings. By December, 1932, famed big-band leader Horace Heidt had taken a keen interest in the futuristic sounds of Rey’s electric guitar. So he invited Rey to join his Brigadiers without an audition, and Rey took his place on New Year’s Day, 1933.

Rey’s San Francisco base gave him a national audience, thanks to NBC radio, and the importance of Rey’s performances was recognized by Metronome magazine, which documented the groundbreaking event in February, 1933, saying, “San Francisco… An electric guitar that can be heard over the air, but not in the studio, has been introduced by Alvino Rey at NBC headquarters. The guitar is equipped with an electric amplifier. The result is a much sweeter melody without overtones…”

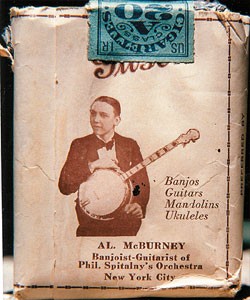

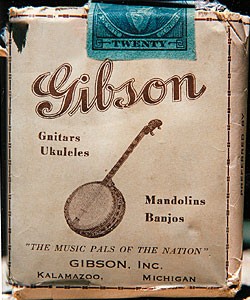

In May, 1935, after more than two years of playing six days a week at the Golden Gate, Heidt’s Brigadiers headed to Chicago to the Drake Hotel’s opulent Silver Forest Room. It would be the first leg of a tour that would take the now nationally famous band through the Midwest and along the East Coast. This fortuitous event also marked the rekindling of a professional relationship that began in 1928, when the Gibson Company featured a rising young musician named Alvin McBurney (he wouldn’t be Alvino Rey for another year) on promotional packs of Gibson-branded cigarettes.

Rey in a 1935 pub photo for the Horace Heidt band, with a custom-built Rickenbacker.

Front and back of Gibson cig pack with photo of Alvin McBurney, before he took the stage name Alvino Rey.

The crowd at the Silver Forest Room typically consisted of everyone from the heads of corporations like U.S. Steel and Coca-Cola to average couples out on the town. But for Gibson general manager Guy Hart, the visit was an opportunity to land a star endorser. Hart had watched as the electric guitar business grew from experiment to opportunity, and he wanted Gibson in on the action. The company gained quick respect for its flat-top line in the late 1920s, in part by associating with pop music star Nick Lucas. And it had recently gained the support of vaudeville multi-instrumentalist Roy Smeck, who played a pair of acoustic Hawaiian models. What luck for Hart that an old friend, now the number one electric-guitar player in the country, was across the lake from Kalamazoo. And he had more in mind than a simple endorsement!

Asked about meeting Hart that night, Rey said, “He asked if I would help them come up with ideas for an electric guitar.” Rey agreed to help, and Hart teamed him with John Kutilek, an electronics engineer at Lyon & Healy. “We made bodies out of wood, then out of brass… we tried a number of things,” Rey added. But their primary goal was to devise a patentable pickup design. However, after a few months, Rey had to step away from the project when Heidt’s band went on the road. Hart then brought it to the Kalamazoo plant and assigned it to Walter Fuller, head of Gibson’s new electronic “department,” which was, in reality, a solo effort. Fuller took a fresh look, and by the end of October, Gibson was shipping the new cast-aluminum E-150 electric Hawaiian guitar.

Though Rey’s direct involvement with the electric pickup had ended, his relationship with Gibson grew stronger after the Drake Hotel became a sort of home base for Heidt’s band, which would play there for a few months at a time between road trips. He became a test artist, idea guy, and primary endorser. He explained, “I would fly up to the plant a one or two time a week and we would try out new ideas.” And Hart often made the trip from Kalamazoo to watch the band and chat with Rey. Their working relationship grew ever stronger, and Hart would often hang out after the show to discuss ideas for improving Gibson’s new line of electric instruments.

In early summer, 1936, Heidt’s Brigadiers began their third stint at the Drake, and began hosting a nationally broadcast radio program. Heidt’s group was more than a dance band – it served up music with entertainment, like a sophisticated vaudeville show – and Rey was often featured with his electric Hawaiian guitar, which he could manipulate to sound like a human voice forming words. Band members would exchange and play each other’s instruments. And the four King Sisters, the band’s vocalists, would dance into the audience and schmooze with club patrons.

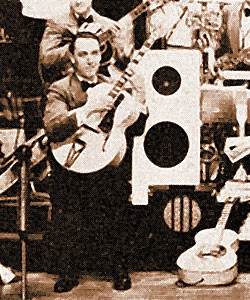

Horace Heidt’s Brigadiers at the Drake hotel Silver Forest Room, Fall, 1935. Rey is in front, holding a custom-built Gibson Super 400; note his speaker cab “stack!”

In one popular skit, band members played miniature instruments – piano, drums, violin, and trumpet. One evening, while the “miniature group” performed, Rey took his break at a table with Hart and talked about not being able to join in on the fun since he didn’t have an instrument that “fit” the bill. Rey remembered it as nothing more than a passing thought, and that Hart seemed to simply nod. But within a month, Hart was back and, as the band was getting ready to take a break, he motioned for Rey to join him. They chatted for a few minutes, and then from under the table he produced two small cases. “Go ahead, open them,” he said. Rey was taken by surprise; he had all but forgotten their conversation, though Gibson’s general manager hadn’t!

Rey worked his new instruments (see details in the “Mini Makeup” sidebar) into the miniature act, eventually devising a routine where Rey would play his larger console Hawaiian electric, making it sound as though it were in distress before he “delivered” the baby electric from underneath the larger instrument. He then made the mini sound like an infant crying. “It got a hell of a laugh,” he recalled.

In January, 1997, Rey and Kutilek attended the annual NAMM music-industry trade show in Anaheim, California, following the rediscovery of the experimental Gibson electric guitar. Sitting in the company’s booth next to the display of the prototype, Rey renewed old acquaintances and met a number of contemporary players who cited him as influential. And his place in electric-guitar history became more secure when a group of people approached the booth, surrounding a figure in black leather and a top hat. As the latter-day guitar god fans know as Slash slowed to look at the crude metal frame, he stopped, looked at the man at the table, and asked, “Are you Alvino Rey?” Rey nodded. “You’re one of my heroes!” Slash told him.

Despite his enormous popularity in the 1930s, Rey remains one of the unsung heroes of the electric guitar. In an age when the acoustic guitar was the dominant fretted instrument (having conquered the tenor banjo) and the electric guitar was passed off by many as a novelty or gimmick, Rey gave it a “voice.” Most histories of electric guitarists begin with Charlie Christian (with a passing nod to Eddie Durham), but it was Alvino Rey who helped the electric guitar gain acceptance in popular music in the mid 1930s.

Special thanks to Arian Sheet of the National Music Museum, and Walter Carter, Gruhn Guitars.

Author Lynn Wheelwright can be reached at gmtgtrs@msn.com.

Mini Makeup

Measuring 19″ with 8″ x 51/2″ bodies and top-of-the-line L-5 features, Alvino Rey’s mini Gibson instruments are constructed to the company’s highest standards.

The electric is made from a solid piece of curly maple, with a miniature version of the famed “Charlie Christian” bar pickup from the ES-150 in its hollowed cavity. The acoustic is a diminutive version of an f-hole guitar with a flat top, hand-built miniature trapeze tailpiece, and archtop-style bridge.

The pair sport matching ebony fingerboards, pearl-block fret markers, and the famed torch peghead inlay from the L-5. The tuners appear to be a modified mandolin set, and the peghead backs are painted black with the V-point found on the best models of the period.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s February 2009 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.